Small and precise: These are the ideal characteristics for CRISPR systems, the Nobel-prize winning technology used to edit nucleic acids like RNA and DNA.

Rice University scientists have described in detail the three-dimensional structure of one of the smallest known CRISPR-Cas13 systems used to shred or modify RNA and employed their findings to further engineer the tool to improve its precision. According to a study published in Nature Communications, the molecule works differently than other proteins in the same family.

“There are different types of CRISPR systems, and the one our research was focused on for this study is called CRISPR-Cas13bt3,” said Yang Gao, an assistant professor of biosciences and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Scholar who helped lead the study. “The unique thing about it is that it is very small. Usually, these types of molecules contain roughly 1200 amino acids, while this one only has about 700, so that’s already an advantage.”

A diminutive size is a plus as it allows for better access and delivery to target-editing sites, Gao said.

Unlike CRISPR systems associated with the Cas9 protein ⎯ which generally targets DNA ⎯ Cas13-associated systems target RNA, the intermediary “instruction manual” that translates the genetic information encoded in DNA into a blueprint for assembling proteins.

Researchers hope these RNA-targeting systems can be used to fight viruses, which generally encode their genetic information using RNA rather than DNA.

“My lab is a structural biology lab,” Yang Gao said. “What we are trying to understand is how this system works. So part of our goal here was to be able to see it in three-dimensional space and create a model that would help us explain its mechanism.”

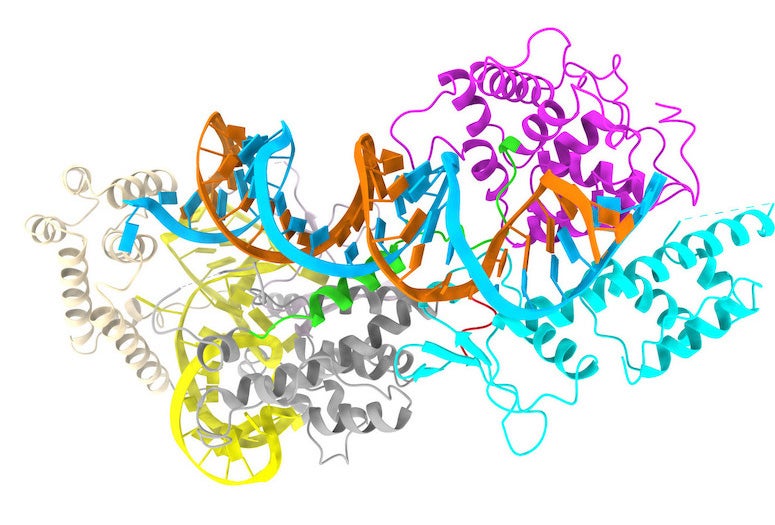

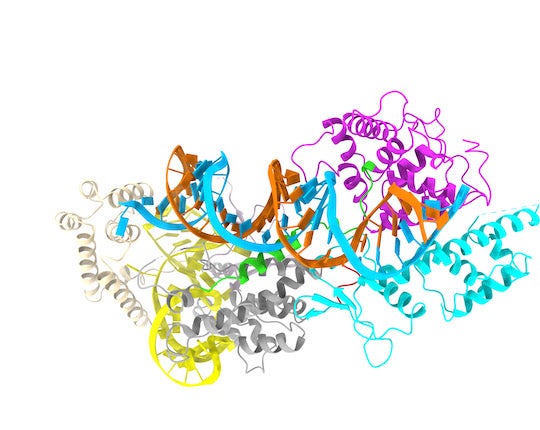

The researchers used a cryo-electron microscope to map the structure of the CRISPR system, placing the molecule on a thin layer of ice and shooting a beam of electrons through it to generate data that was then processed into a detailed, three-dimensional model. The results took them by surprise.

“We found this system deploys a mechanism that’s different from that of other proteins in the Cas13 family,” Yang Gao said. “Other proteins in this family have two domains that are initially separated and, after the system is activated, they come together ⎯ kind of like the arms of a scissor ⎯ and perform a cut.

“This system is totally different: The scissor is already there, but it needs to hook onto the RNA strand at the right target site. To do this, it uses a binding element on these two unique loops that connect the different parts of the protein together.”

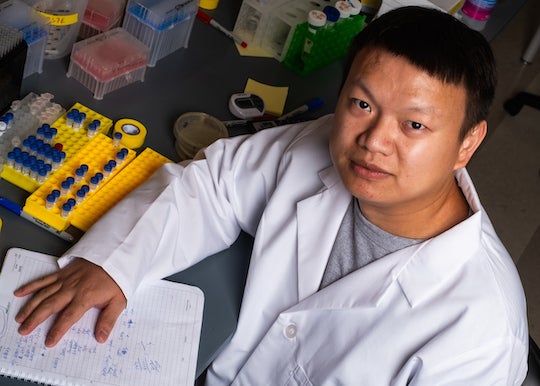

Xiangyu Deng, a postdoctoral research associate in the Yang Gao lab, said it was “really challenging to determine the structure of the protein and RNA complex.”

“We had to do a lot of troubleshooting to make the protein and RNA complex more stable, so we could map it,” Deng said.

Once the team figured out how the system works, researchers in the lab of chemical and biomolecular engineer Xue Sherry Gao stepped in to tweak the system in order to increase its precision by testing its activity and specificity in living cells.

“We found that in cell cultures these systems were able to hone in on a target much easier,” said Sherry Gao, the Ted N. Law Assistant Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. “What is really remarkable about this work is that the detailed structural biology insights enabled a rational determination of the engineering efforts needed to improve the tool’s specificity while still maintaining high on-target RNA editing activity.”

Emmanuel Osikpa, a research assistant in the Xue Gao lab, performed cellular assays that confirmed the engineered Cas13bt3 targeted a designated RNA motif with high fidelity.

“I was able to show that this engineered Cas13bt3 performed better than the original system,” Osikpa said. “Xiangyu’s comprehensive study of the structure highlights the advantage that a targeted, structurally guided approach has over large and costly random mutagenesis screening.”

The research was supported by the Welch Foundation (C-2033-20200401, C-1952), the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR190046), the National Science Foundation (2031242) and the Rice startup fund.

- Peer-reviewed paper:

-

“Structural basis for the activation of a compact CRISPR-Cas13 nuclease” | Nature Communications | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-41501-5

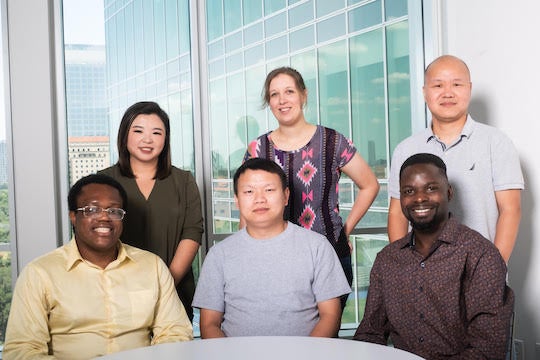

Authors: Xiangyu Deng, Emmanuel Osikpa, Jie Yang, Seye J. Oladeji, Jamie Smith, Xue Gao and Yang Gao - Image downloads:

-

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/09/Selected_Gao.jpg

CAPTION: Emmanuel Osikpa (from left), Xue Sherry Gao, Xiangyu Deng, Jamie Smith, Seye J. Oladeji and Yang Gao (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/09/230810_Gao_Fitlow_012.jpg

CAPTION: Xiangyu Deng (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/09/230810_Gao_Fitlow_036.jpg

CAPTION: Emmanuel Osikpa (from left) and Xiangyu Deng (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/09/CRISPR-Cas13bt3_img2.jpg

CAPTION: Model of a minimal CRISPR-Cas13bt3 molecule generated with a cryo-electron microscope. The RNA to be recognized and cleaved is colored in light blue, while the scissor is formed by the magenta and cyan colored domains. The two loops for controlling the CRISPR-Cas13bt3 are shown in green and red. (Image courtesy of the Yang Gao lab/Rice University)

- Related stories:

-

Rice scientists reengineer cancer drugs to be more versatile:

https://news.rice.edu/news/2023/rice-scientists-reengineer-cancer-drugs-be-more-versatile

DNA repair scheme gets closer look for cancer therapy:

https://news.rice.edu/news/2023/dna-repair-scheme-gets-closer-look-cancer-therapy

New enzyme could mean better drugs:

https://news.rice.edu/news/2023/new-enzyme-could-mean-better-drugsRice University scientists get fungi to spill their secrets:

https://news.rice.edu/news/2023/rice-university-scientists-get-fungi-spill-their-secrets

Rice models moving ‘washers’ that help DNA replicate:

https://news.rice.edu/news/2022/rice-models-moving-washers-help-dna-replicate - Links:

-

Yang Gao lab: https://yanggaolab.blogs.rice.edu/

Xue Sherry Gao lab: xuegaolab.org

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering: https://chbe.rice.edu/

BioScience Research Collaborative: https://brc.rice.edu/

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu

- About Rice:

-

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,552 undergraduates and 3,998 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 4 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.