Knowing how a changing climate impacts the planet’s water cycle is critical to informed, effective water and climate policies, especially in light of growing concern over water scarcity.

A new study by Rice University climate scientist Sylvia Dee and an international team of collaborators sheds light on the impact that global temperature variation over the past 2,000 years has had on the planet’s hydrological cycle.

By tracking water isotopes ⎯ atom types of varying atomic mass ⎯ and climate data preserved in sediments, rocks, tree rings, corals, ice sheets and other natural archives, researchers found that when global temperature is higher, rain and other environmental waters become more isotopically heavy.

“Isotopes are a really powerful tool for understanding past changes in the hydrological cycle,” said Dee, assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences and civil and environmental engineering. “One of the things I specialize in is adding water isotope tracers into climate models and using them to understand past variations in the water cycle.”

The water cycle is complex, and rainfall in particular has geographic variations that are much more drastic than air temperature. This has made it difficult for scientists to evaluate how rainfall has changed over the past 2,000 years.

“We decided to start with water isotope records because they reflect holistic signals and because they’re recorded in all kinds of different natural archives,” said Bronwen Konecky, assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and lead author of the study in Nature Geoscience. “This is a first step toward reconstructing drought or rainfall patterns at the global scale during the past 2,000 years.”

Dee and fellow climate modelers on the PAGES Iso2k project team — which includes more than 30 researchers from 10 countries — integrated water isotope modeling data with the vast paleoclimate dataset assembled for the project. Dee said this merger of information will make it possible to evaluate climate models’ accuracy based on how well they align with variability patterns inferred from the dataset.

“That’s really important, because if we want to use climate models to make projections about future rainfall, we have to make sure that they’re hitting targets in the past correctly,” Dee said. “This is one of the ways that we check that their physics schemes are correct.”

The team collected, collated and sometimes digitized datasets from hundreds of studies to build the database it used in its analysis. The group ended up with 759 different time series, representing the world’s largest integrated database of water isotope proxy records.

“The major advance here is that we’ve created this very comprehensive database based on real measurements from all over the world,” Dee said. “It’s amazing to have these records — ice cores from the top of the Andes, corals from the tropical Pacific or tree rings from the Himalayas — and see that they’re showing coherent signals of how the water cycle is shifting over time.

“Being able to bring these data types under one roof allows us to carry out large scale analyses of global patterns of water cycle changes in a warming climate, which is very novel. I think this dataset is going to be a really powerful tool for understanding how rainfall might change in the future in different regions.”

The research was supported by the Swiss Academy of Sciences, the National Science Foundation (1805141, 1433408, 1948746, 1805143, 2202794, 2145725, 2103035, 2002444, 1945479, 1931242, 2002460, 2102931, 1805702, 1349595, 1652274, 1504267, 1737716, 2044616, 1847791), the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Australian Research Council (DP170100557, CE170100023, DP190102782, LP210300691, FT160100029), the South Central Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperative Agreement (G19AC00086), the Spanish National Research Council (RYC‐2013‐14073, LINKA20102, CEX2018‐000794‐S), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NA18OAR4310427), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01LP1922A, 21-17-00006), the German Research Foundation (OP217/2-1, OP217/3-1, OP217/4-1), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grants (RGPIN-2016-06730, RGPIN-2021-03888), Special Research Initiative for the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (SR200100008),the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CE170100023) and Australian Antarctic Division grants (757, 4061, 4062, 4537).

- Peer-reviewed paper:

-

“Globally coherent water cycle response to temperature change during the past two millennia” | Nature Geoscience | DOI: 10.1038/s41561-023-01291-3

Authors: Bronwen Konecky, Nicholas McKay, Georgina Falster, Samantha Stevenson, Matt Fischer, Alyssa Atwood, Diane Thompson, Matthew Jones, Jonathan Tyler, Kristine DeLong, Belen Martrat, Elizabeth Thomas, Jessica Conroy, Sylvia Dee, Lukas Jonkers, Olga Churakova, Zoltán Kern, Thomas Opel, Trevor Porter, Hussein Sayani, Grzegorz Skrzypek, Nerilie Abram, Kerstin Braun, Matthieu Carré, Olivier Cartapanis, Laia Comas-Bru, Mark Curran, Emilie Dassié, Michael Deininger, Dmitry Divine, Alessandro Incarbona, Darrell Kaufman, Nikita Kaushal, Robert Klaebe, Hannah Kolus, Guillaume Leduc, Shreya Managave, P. Graham Mortyn, Andrew Moy, Anais Orsi, Judson Partin, Heidi Roop, Marie-Alexandrine Sicre, Lucien von Gunten and Kei Yoshimura

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-023-01291-3 - Image Downloads:

-

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/10/Dee_Feb2023-6098-sm-1.jpg

CAPTION: Sylvia Dee is an assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences and civil and environmental engineering at Rice University. (Photo courtesy of Sylvia Dee/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/11/PBAF-9420_0031-1.jpg

CAPTION: Bronwen Konecky at Washington University in St. Louis sorts material from lake sediment collected at Lake Sibinacocha in Peru. (Photo by Thomas Malkowicz/Washington University in St. Louis)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/11/IMG_5484.jpeg

CAPTION: Elizabeth K. Thomas, associate professor at the University at Buffalo and a colleague study lake sediment collected on Greenland. (Photo by Margie Turrin)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/11/P601033020100601_82.jpg

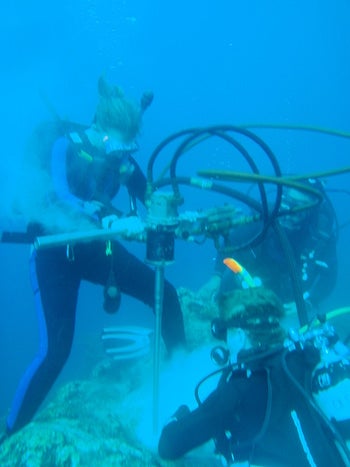

CAPTION: Diane Thompson from the University of Arizona drills corals in the Galapagos Islands. (Photo courtesy of Diane Thompson/University of Arizona)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/11/IMG_5523.jpeg

CAPTION: Karlee Prince, a Ph.D. student at the University at Buffalo, holds a lake sediment core collected on Greenland. (Photo by Elizabeth K. Thomas)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/11/DSCF3216.jpg

CAPTION: Thunderstorm over the Mekong River in Laos. (Photo by Chris Havlin)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/11/PBAF-9420_0035.jpg

CAPTION: Bronwen Konecky at Washington University in St. Louis conducted paleoclimate investigations at Lake Sibinacocha in Peru. (Photo by Thomas Malkowicz/Washington University in St. Louis)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/11/P5260008.jpeg

CAPTION: Georgy Falster, Australian National University, presenting data. (Photo courtesy of Georgy Falster/Australian National University)

- Related stories:

-

Most but not all Texas coaches say they’ll plan for climate change:

https://news.rice.edu/news/2022/most-not-all-texas-coaches-say-theyll-plan-climate-changeSylvia Dee wins fellowship to launch Gulf of Mexico study:

https://news.rice.edu/news/2021/sylvia-dee-wins-fellowship-launch-gulf-mexico-study - Links:

-

Dee lab: https://sylviadeeclimate.org/

Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences: https://eeps.rice.edu/

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: https://naturalsciences.rice.edu/

Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering: https://cee.rice.edu/George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu/

- About Rice:

-

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,552 undergraduates and 3,998 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 4 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.