As the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Harvey approaches, Rice University experts are available to discuss the storm’s ongoing impact.

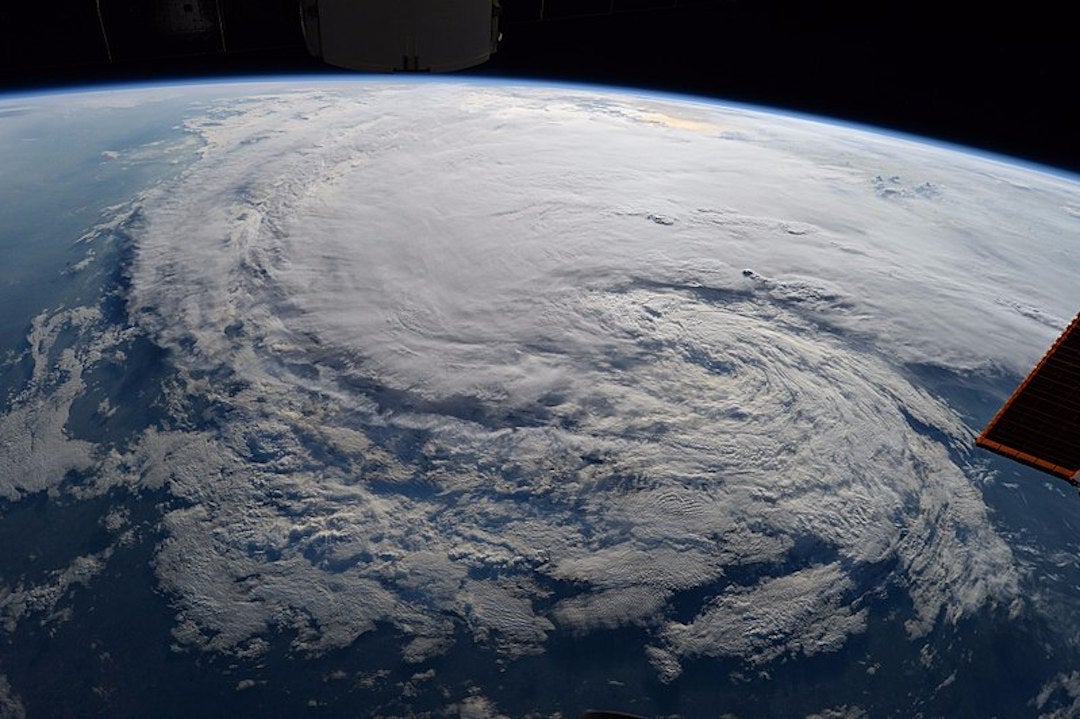

Hurricane Harvey remains the most intense rainfall event in U.S. history . It struck Texas Aug. 25 and stalled for four days, producing catastrophic flooding and claiming 68 lives. Harvey caused $148 billion in damage , making it the second costliest hurricane in U.S. history behind 2005's Katrina.

Phil Bedient , the Herman Brown Professor of Engineering and department chair of civil and environmental engineering, is co-author of one of the nation’s most widely used textbooks on flooding, a pioneer in the use of technology for flood prediction and early warning, and the director of Rice’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters ( SSPEED) Center. The Flood Alert System (FAS5) Bedient designed in the 1990s for Rice and the Texas Medical Center is in its fifth technological generation and served as a model for the Flood Information and Response System (FIRST) Bedient and Rice students created for high-risk portions of Houston .

“Houston is now considered the most flood-prone city in America,” Bedient said. “The devastation and pain from Harvey affected almost everyone, and the aftermath of repair and rebuild has lasted for years.”

Harvey was just the latest in a string of major floods to strike Houston, but “there has been a noted increase in the intensity and frequency of these massive events since Tropical Storm Allison in 2001,” Bedient said. “My hope for the future is that community leaders and the building industry in Houston will actually learn from the past 20 years of repetitive flooding and begin to truly implement well-planned drainage and storage systems that work, both at local and regional levels.

“I cannot stress enough the importance of green space and planned detention as major components of any plan for Houston,” he said. “I know these methods work, since the flood damage in well-planned communities in Fort Bend County during Harvey was far less than in Harris County.”

Bedient also stressed the importance of implementing equitable flood control in ways that treat both high- and low-income areas fairly.

“There will be other bigger and more frequent Texas storms and hurricanes in the future, and we all must be vigilant and prepared for this new reality,” Bedient said. “The technologies for control are all there, but they have to be implemented by our leaders.”

Jim Blackburn is a professor in the practice of environmental law, a faculty scholar at the Baker Institute for Public Policy, director of Rice’s undergraduate minor in energy and water sustainability and co-director of the SSPEED Center.

“Harvey was a climate change-influenced storm event and a forerunner of what the future holds for our region,” Blackburn said. “At all levels of government, we lack the expertise and tools to adequately address our changing climate. We have been crippled by the bickering on this issue. It is time for science to lead us rather than politics. Our lives and livelihoods depend on it.”

Dominic Boyer , founding director of Rice’s Center for Environmental Studies and a professor in the Department of Anthropology, is a cultural anthropologist whose research focuses on climate mitigation and climate adaptation. Following Hurricane Harvey he led a National Science Foundation-funded project to investigate the social and emotional burdens of recurring catastrophic flooding and why some Houstonians chose to remain and rebuild while others decided to move on from their homes, neighborhoods and even the city itself. He is currently working in the Kashmere/Trinity/Houston Gardens neighborhoods of northeast Houston, researching how green stormwater infrastructure could help climate resilience in Houston’s historically underserved regions.

“Five years on from Hurricane Harvey, Houston remains exceedingly vulnerable to the more intense rainfalls and supercharged tropical storm systems associated with climate change,” he said. “But with much greater political attention and coordination over the past few years, Houston is also on the cusp of making real progress on climate resilience for the first time in its history. So many good things are happening here now that it’s hard not to be optimistic about the longer-term picture even as hurricane season rolls around.”

Daniel Cohan is an environmental engineer who researches air pollution, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering and a Rice faculty scholar at the Baker Institute. He authored the 2022 book “ Confronting Climate Gridlock .”

“Hurricane Harvey was a wake-up call for me to see how climate change is supercharging storms, and it became the inspiration for me to write ‘Confronting Climate Gridlock,’” Cohan said. “The record-shattering rainfall rates from Harvey would have been almost impossible without the warming to date, and could grow even larger in future storms as temperatures continue to rise.

“Harvey also opened my eyes to how vulnerable our industries are to extreme weather and power outages,” he said. “Chemical plants and refineries have made tremendous strides in installing pollution controls, but their operations can be disrupted by extreme events, as we saw with the spikes in emissions that followed the storm.”

Adrienne Correa is an assistant professor of biosciences and a marine biologist who studies coral reef ecosystems, animals, microbiomes and global change. She has served on the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council and has worked as part of a team of scientists to predict the impacts of climate stressors on coral reefs in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean.

Harvey produced an estimated 19 trillion gallons of rainfall that carried pollution from flooding into the Gulf of Mexico. A few weeks after the storm, when salinity levels dropped 10% in one day at the Flower Garden Banks about 100 miles offshore of Galveston, Correa organized a research expedition to investigate. It found the reefs had been polluted by floodwater from both Harvey and Houston’s 2016 Tax Day floods.

“Extreme storms are becoming more harmful due to climate change, including the potential for increased precipitation and flooding,” Correa said. “And the damage caused by storms doesn’t just harm humans; it can destabilize coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass beds that protect our coasts and support fishing and tourism industries. Floodwaters in the Houston area after Hurricane Harvey contained extremely high levels of bacteria associated with human waste, and we found those floodwaters traveled far offshore, carrying that harmful bacteria to Texas’ backyard coral reef, the Flower Garden Banks.

“Our actions on land impact the ocean and organisms that live in it,” she said. “When we pave over a large portion of the land — like we have in the Houston area — it makes flooding more likely. We need to ensure that our stormwater and wastewater management systems are prepared for extreme storms along the Texas coast.

“By taking immediate and significant actions to fight climate change, we move away from conditions that could contribute to potentially damaging storms in the future, and that’s good for people and ocean ecosystems alike,” Correa said.

Sylvia Dee , a climate scientist and an assistant professor of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences , said tropical cyclones are likely to become more intense and costly due to climate change.

“The numbers will keep growing alongside global warming,” Dee said. “Observations and models agree that storm intensity and wind speeds will increase, storms will become rainier, and sea level-rise will induce higher storm surge and subsequent inundation, placing a larger coastal area at risk.”

She said continued development and population growth along the coast will magnify damages from future tropical cyclones.

“Most coastal communities are not prepared for the sea level-rise and storms they will see in the future,” Dee said. “Communities will need to make tough decisions, including plans for managed retreat to higher elevations.

“Imagine it is 2050,” she said. “Sea levels are rising and tropical cyclones are more intense. U.S. coastal communities are facing chronic, disruptive flooding that directly affects people's lives. How will we have changed the way we develop our coastline in the Galveston Bay and Houston area? There is a critical need to consider future tropical cyclone risk in long-term planning and decision-making such as how and where infrastructure is developed.”

Jim Elliott , a professor of sociology and a faculty affiliate with Rice’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research, is an expert in social inequality and the environment, and studies the intersection of natural and industrial hazards.

“From a sociological perspective, environmental hazards such as Hurricane Harvey do not cause disasters,” Elliott said. “The social forces that weaken and divide us do, leaving some communities more vulnerable than others not just to dramatic climatic events but also to the long and unequal recoveries that often follow. Thus, the road to resilience will run not just through bigger and more expensive infrastructure but also policies, actions and commitments that actually focus on those of us most in need. This insight forms the core of the FEMA National Advisory Council's recent recommendations and presents the real challenge ahead."

Ed Emmett , a fellow in energy and transportation policy at Rice’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, was county judge of Harris County during Harvey. As the chief executive of the county in which Houston is located, Emmett was one of the most prominent government leaders tasked with steering the community through the greatest disaster in its history. He can speak about what is required to make a community resilient to natural and manmade disasters.

“Making a community resilient to disasters is an ongoing process which requires taking lessons learned from past disasters and using those lessons to prepare for the future,” he said. “The rains spawned by Harvey were unprecedented, but our area is better protected now because of lessons learned.”

Pedram Hassanzadeh is an assistant professor of mechanical engineering and of Earth, environmental and planetary sciences. His expertise is in atmospheric dynamics, climate change, extreme weather events, and the application of large-scale computing and data science to the study of climate systems. Following Harvey, Hassanzadeh led a three-year study that found climate change will likely intensify hurricane-steering winds over Texas in the final 25 years of this century. That could decrease the odds of slow-moving hurricanes like Harvey and increase the chances of fast-moving storms like 2008’s Hurricane Ike, which raced across Texas in less than a day and pounded the Ohio River Valley with hurricane-force winds that caused record power outages.

“We know global warming will intensify hurricane rainfall by driving up water temperatures in the Gulf and by allowing the atmosphere to hold more moisture,” Hassanzadeh said. “The slow movement of Hurricane Harvey was a major factor in the record-breaking rain in Houston, and it generated significant concerns that climate change might worsen the flooding impacts of future hurricanes by making them more likely to move slowly or stall.

“In our work, we found that the movement of future Texas hurricanes will be controlled by several confounding factors,” he said. “It’s a complex environment that needs more research. Understanding whether future hurricanes in our region are more likely to move slowly like Harvey or rapidly like Ike is essential for better preparing for these events through the development of protective measures and strengthening infrastructure.”

Cymene Howe , a professor of anthropology and a faculty affiliate in the Center for Environmental Studies at Rice, is a cultural anthropologist who researches the relationship between social and environmental systems, specializing in anthropogenic climate change, hydrological impacts and collective responses to ecological precarity.

“We are beginning to make steps in the right direction to avert the worst outcomes of climate change,” Howe said. “However, our Earth system has many years of damage already built into it and that means we need to be prepared for more catastrophic rainfall events like Hurricane Harvey.”

Howe said preparation beforehand is crucial, especially when it comes to the most vulnerable in the Houston community.

“We cannot afford to see our communities as fully insulated from environmental forces,” she said. “Climate change is now knocking on all our doors and creeping up our doorsteps, but with foresight and collective effort we can better respond to the storms that will inevitably come.”

Danielle King , an assistant professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences , is an industrial and organizational psychologist. She is an expert on resilience and race, primarily in the context of workplace experiences and outcomes.

“Any efforts to foster employee resilience require support from organizational leaders and a consideration of how race shapes our experiences with large-scale, naturally occurring adversities such as hurricanes" she said. “I am inspired by and drawn to the ‘Houston Strong’ motto and the city’s ongoing resilience efforts. These efforts and communities embody many of the characteristics important for resilience, such as social support, shared identity and resources.”

Tom Miller is an associate professor of biosciences who studied the impacts of Harvey on ants in East Texas.

“What really surprised us was how resilient these species are,” Miller said. “Ants nest in the ground, so we expected them to be wiped out in heavily flooded areas. Instead, the samples we retrieved after the storm looked very much like pre-Harvey samples.”

Miller said invasive ant species like fire ants and tawny crazy ants likely benefited from the storm.

“These invasive ants are opportunists, so a big disruption like Harvey allows them to get a foothold in places where they may have been previously excluded.”

To arrange interviews with Bedient, Blackburn, Cohan, Correa, Dee, Hassanzadeh or Miller, contact Jade Boyd at 713-348-6778 or jadeboyd@rice.edu.

To arrange interviews with Boyer, Elliott, Howe or King, contact Amy McCaig at 713-348-6777 or amym@rice.edu.

To arrange an interview with Emmett, contact Avery Ruxer Franklin at 713-348-6327 or averyrf@rice.edu.