There’s still plenty of room at the bottom to generate piezoelectricity. Engineers at Rice University and their colleagues are showing the way.

A new study describes the discovery of piezoelectricity — the phenomenon by which mechanical energy turns into electrical energy — across phase boundaries of two-dimensional materials.

The work led by Rice materials scientists Pulickel Ajayan and Hanyu Zhu and their colleagues at Rice’s George R. Brown School of Engineering, the University of Southern California, the University of Houston, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base Research Laboratory and Pennsylvania State University appears in Advanced Materials.

The discovery could aid in the development of ever-smaller nanoelectromechanical systems, devices that could be used, for example, to power tiny actuators and implantable biosensors, and ultrasensitive temperature or pressure sensors.

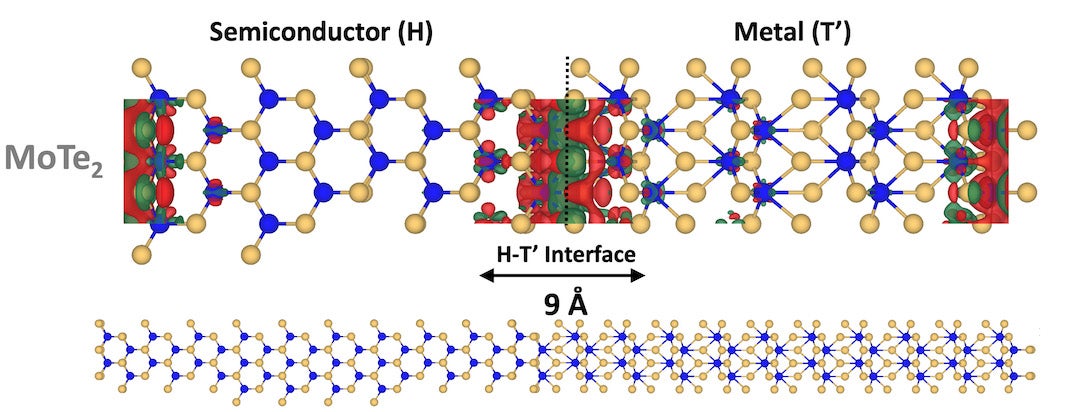

The researchers show the atomically thin system of a metallic domain surrounding semiconducting islands creates a mechanical response in the material’s crystal lattice when subjected to an applied voltage.

The presence of piezoelectricity in 2D materials often depends on the number of layers, but synthesizing the materials with a precise number of layers has been a formidable challenge, said Rice research scientist Anand Puthirath, co-lead author of the paper.

“Our question was how to make a structure that is piezoelectric at multiple thickness levels — monolayer, bilayer, trilayer and even bulk — from even non-piezoelectric material,” Puthirath said. “The plausible answer was to make a one-dimensional, metal-semiconductor junction in a 2D heterostructure, thus introducing crystallographic as well as charge asymmetry at the junction.”

“The lateral junction between phases is very interesting, since it provides atomically sharp boundaries in atomically thin layers, something our group pioneered almost a decade before,” Ajayan said. “This allows one to engineer materials in 2D to create device architectures that could be unique in electronic applications.”

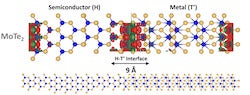

The junction is less than 10 nanometers thick and forms when tellurium gas is introduced while molybdenum metal forms a film on silicon dioxide in a chemical vapor deposition furnace. This process creates islands of semiconducting molybdenum telluride phases in the sea of metallic phases.

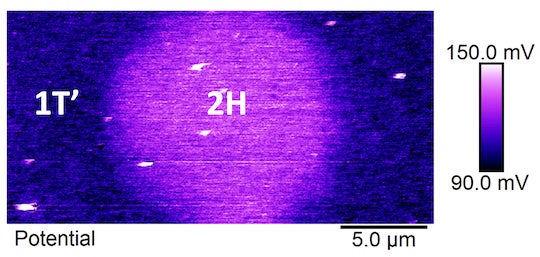

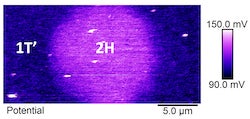

Applying voltage to the junction via the tip of a piezoresponse force microscope generates a mechanical response. That also carefully measures the strength of piezoelectricity created at the junction.

“The difference between the lattice structures and electrical conductivity creates asymmetry at the phase boundary that is essentially independent of the thickness,” Puthirath said. That simplifies the preparation of 2D crystals for applications like miniaturized actuators.

“A heterostructure interface allows much more freedom for engineering materials properties than a bulk single compound,” Zhu said. “Although the asymmetry only exists at the nanoscale, it may significantly influence macroscopic electrical or optical phenomena, which are often dominated by the interface.”

Research scientist Xiang Zhang and graduate student Rui Xu of Rice and postdoctoral researcher Aravind Krishnamoorthy of the University of Southern California are co-lead authors of the paper. Co-authors are graduate student Jiawei Lai, research professor Robert Vajtai and lecturer Venkataraman Swaminathan of Rice; Priya Vashishta, a professor of chemical engineering and materials science, biomedical engineering, computer science and physics and astronomy at the University of Southern California; graduate student Farnaz Safi Samghabadi and Dmitri Litvinov, the John and Rebecca Moores Professor at the University of Houston; David Moore and Nicholas Glavin of the Air Force Research Laboratory, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base; and Rice alumni Tianyi Zhang and Fu Zhang, graduate student David Sanchez and Mauricio Terrones, the Verne M. Willaman Professor of Physics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Zhu is an assistant professor of materials science and nanoengineering. Ajayan is the Benjamin M. and Mary Greenwood Anderson Professor in Engineering and a professor of materials science and nanoengineering, chemistry, and chemical and biomolecular engineering. He is also chair of Rice’s Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-18-1-0072, FA9550-19RYCOR050) and the National Science Foundation (2005096) supported the research.

- Peer-reviewed research

-

Piezoelectricity across two-dimensional phase boundaries: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adma.202206425

- Images for download

-

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/08/0815_PIEZO-1-WEB.jpg

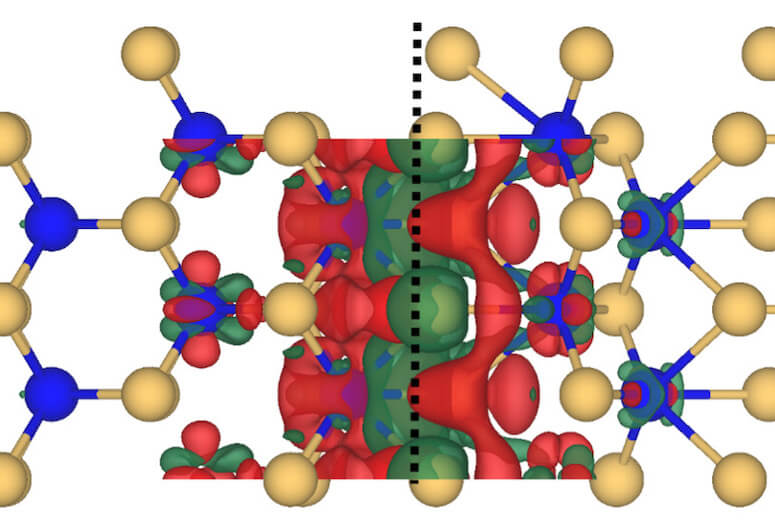

A charge redistribution model shows how charge flows across the phase interfaces in a 2D piezoelectric material of molybdenum (blue) and tellurium (yellow). The red areas are electro-deficient, the green is electron rich. Voltage from a microscope tip distorts the lattice and creates dipoles at the boundary between the atoms. (Credit: Ajayan Research Group/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/08/0815_PIEZO-2-WEB.jpg

An image from a Kelvin probe force microscope shows the electronic potential distribution across the metallic and semiconductor phases of MoTe2. A team of researchers led by Rice University discovered piezoelectricity across phase boundaries in the material. (Credit: Ajayan Research Group/Rice University)

- Related materials

-

Magnetene’s ultra-low friction explained: https://news.rice.edu/news/2021/magnetenes-ultra-low-friction-explained

Ajayan Research Group: https://ajayan.rice.edu

Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering: https://msne.rice.edu

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu

- About Rice

-

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,240 undergraduates and 3,972 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.