To escape into Mexico during slavery in the 1800s, Sallie Wroe’s father strung together bales of cotton and rowed across the Rio Grande River with other enslaved people. He spent years south of the border, and when he did eventually return to the United States, he spoke Spanish and used his hard-earned wages to buy his family a home and clothing.

This story is one of thousands included in the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Slave Narratives, a collection of oral histories conducted by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s, that documents the experiences of formerly enslaved people in the U.S.

“That level of determination and love is something we rarely get to see so clearly in historical records,” said Rice University senior Daniela Bonscher, sharing what she’d uncovered in the collection.

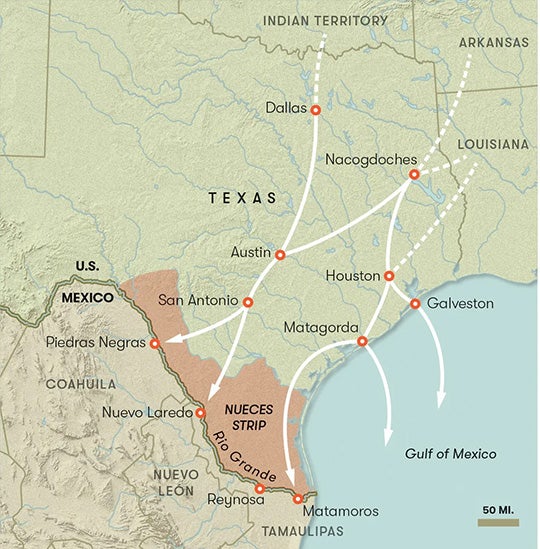

The story of the Underground Railroad – a network of escape routes led by guides or “conductors,” similar to how a railroad operates – typically conjures images of northbound journeys to freedom, but for some enslaved people in Texas, liberation lay across the Rio Grande in Mexico, where slavery was abolished earlier than in the U.S. Bonscher is working to uncover the lesser-known history that exemplifies the resilience and agency of those who sought freedom through this southern route. A native of El Paso, Bonscher stumbled upon the southbound railroad while exploring border histories.

“As someone from El Paso, it’s meaningful to uncover these histories of cross-border solidarity. It highlights the enduring human desire for freedom and dignity,” Bonscher said. “I’ve always been interested in history, but this project has opened my eyes to how much we don’t know. There’s so much history that just doesn’t get taught.”

To piece together these stories, Bonscher has relied on sources like the WPA’s Slave Narrative collection, fugitive slave advertisements and historic newspapers.

“The best part of working with students on research projects is seeing them discover something new,” said Fay Yarbrough, the William Gaines Twyman Professor of History, who has served as Bonscher’s mentor through the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship. “Daniela will sometimes come to my office to tell me about a new source or to talk through an idea, and her face is so expressive that you can watch the discovery happen in her expression.”

The Underground Railroad to Mexico saw people move both ways over the U.S.-Mexico border, Bonscher discovered. Operating through individuals’ personal knowledge of the terrain, the network relied on community support. Escapees passed through major cities such as San Antonio and Austin.

“A lot of people passed through Brownsville because that’s where much of the border-related work took place,” Bonscher said. “Some would move to Mexico, but others came back to Texas with resources and support gained across the border as well.”

In Brackettville, Texas, another popular point along the railroad, freedom seekers found refuge in the Black Seminole community, a group of African Americans and Native Americans who had migrated from Florida. Informed by Augusta “Gigi” Pines of the Seminole Indian Scouts Cemetery Association, Bonscher’s research has been shaped by understanding how the community still thrives there today.

While Bonscher has discovered a wealth of information on the southern Underground Railroad, she said quantifying the scale of patterns of movement remains challenging due to the railroad’s clandestine nature.

“Like with the northbound railroad, you hope no records exist because that means people weren’t caught,” Bonscher said.

Ultimately, Bonscher said she intends for her research to culminate in a history honors thesis at Rice, but her goals extend beyond academic recognition.

“I want people to learn about and process the tough parts of history while recognizing the resilience and agency of those who lived it,” Bonscher said.

“Daniela asks a lot of questions and has the wonderful ability to make connections between what she is learning in different classes,” Yarbrough said. “She is also hyperfocused on thinking about the people we often don’t read about in history. That interest definitely drives her questions and her research project.”

As Bonscher continues her work, she said she hopes to inspire others to question the histories they’ve been taught.

“There’s always more to learn,” Bonscher said. “History isn’t static. It’s alive in the stories we choose to tell and the voices we choose to amplify.”