In the Rice Moody Center for the Arts’ Brown Foundation Gallery, Louise Bourgeois’ “The Couple” suspends two figures in a hanging embrace. The sculpture anchors the fall exhibition “Bio Morphe,” placing the legacy of a 20th-century giant in direct dialogue with a new generation of artists.

“Her interest in forms, materials and the subconscious and psychology, it really resonates with artists today and is still such a source of inspiration,” said Frauke V. Josenhans, curator of the exhibition. “So to have her work in the exhibition in dialogue with this new generation of artists was really important to me.”

From Bourgeois’ suspended forms, “Bio Morphe” expands outward to explore biomorphism — artistic styles inspired by natural patterns and living shapes — through the lens of contemporary materials and ideas.

“It’s a fresh perspective on a concept that has been around for a long time,” Josenhans said. “It really is a living exhibition that features artworks made from latex, plastic zip ties and even bacteria. There are all kinds of different materials and media in this exhibition.”

The works range from Christina Quarles’ fluid paintings that resist fixed identities to Berenice Olmedo’s sculptures incorporating prostheses and orthotics, which challenge assumptions of bodily wholeness. Tishan Hsu’s pieces reflect how digital technologies reshape perception. Together, they underscore the exhibition’s theme: Human bodies and natural forms continually morph, shaped by science, technology and society.

For some artists, the starting point is the smallest scale. Sui Park, who brought “Microcosm” to the Moody’s Central Gallery and Media Art Gallery, transforms disposable cable ties into three-dimensional networks that evoke cellular life. She also created site-specific sculptures for the building’s exterior columns.

“I want to visualize the small living things that we mostly miss or forget in Mother Nature,” said Park, who hand-dyes all the ties for her creations. “With the cable ties, I want to give them a long life in artistic ways and show how man-made materials can visualize Mother Nature in different ways.”

Park’s sculptures stretch across the ground like living organisms complete with thought bubbles hanging from above, though she resists fixing their meaning.

“The audience might have a different way of thinking about my pieces, and I really welcome what they are thinking,” Park said.

Lucy Kim, whose contributions span sculptural paintings and prints made from genetically modified bacteria, also works at the intersection of material science and artistic process.

“The melanin prints are prints on paper. They’re screen-printed bacteria that then, over the course of three days being alive and reproducing, make the melanin. Then the image becomes visible over the course of three days,” Kim said. “That’s where you see the interesting effects of the image bleeding or dripping or growing in a weird way or disappearing in parts. It’s because of the evolutionary process — it’s evolving, dying, living on the paper for three days.”

Kim said her interest in melanin stems from its role as the pigment that shapes human appearance.

“I wanted the paint … to be made with pigments that give humans our appearance,” Kim said. “I learned from there that melanin is the main pigment. Actually, there’s only two. They’re both melanin. It took many years, but then I learned that you could genetically modify bacteria to make melanin for you. From that, I became much more interested in working with the bacteria than just getting inert pigment.”

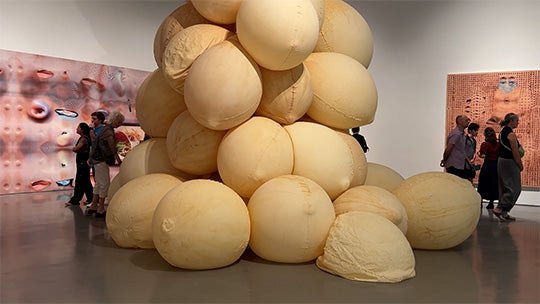

Where Kim’s work grows images into being, Eva Fàbregas’ latex sculptures seem to seep directly from the Moody’s ceiling and stairwells. Her “Exudates” series drapes across the building’s architecture like organic swellings, evoking the fluids released by bodies and trees alike when under stress.

“Exudations are the natural responses of bodies when they have an inflammation or when they have an injury,” Fabregas said. “Trees, they bleed these kinds of viscous substances, one of them being latex. So it’s a natural resin that comes from a tree when it has a wound.”

Fabregas described her work as deeply sensory rather than purely intellectual.

“I think normally (the audience response) doesn’t come from a place of verbal or rational or intellectual expression,” Fabregas said. “I do feel that maybe with my work what happens is that it comes more from the stomach or from the guts, from the skin, from the touch.”

Taken together, the exhibition’s sculptures, paintings and installations reveal a wide spectrum of approaches to biomorphism. Yet they share a common thread, Josenhans said, in their interest in materials, process and the evolving relationship between human bodies and the natural world.

“From sculptures that seem to crawl up the columns to latex forms that take over the architecture, to bacteria on the wall and human bodies emerging from screens — and of course the iconic Louise Bourgeois sculpture anchoring it all — the exhibition really shows how these works live and breathe together,” Josenhans said.

“Bio Morphe” is on view at the Moody until Dec. 20, inviting visitors to witness forms that morph, merge and reimagine the possibilities of art, science and nature. Learn more here.