When a natural disaster devastates a community, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) buyout program is one of the few options for helping residents move to safer ground. But a new interactive tool created at Rice University shows that the vast majority of people aren’t relying on FEMA at all, which has major implications for resilience.

“No one’s been able to really map these moves in the past,” said Jim Elliott, the David W. Leebron Professor of Sociology and co-director of Rice’s Center for Coastal Futures and Adaptive Resilience (CFAR). “It’s a real innovation.”

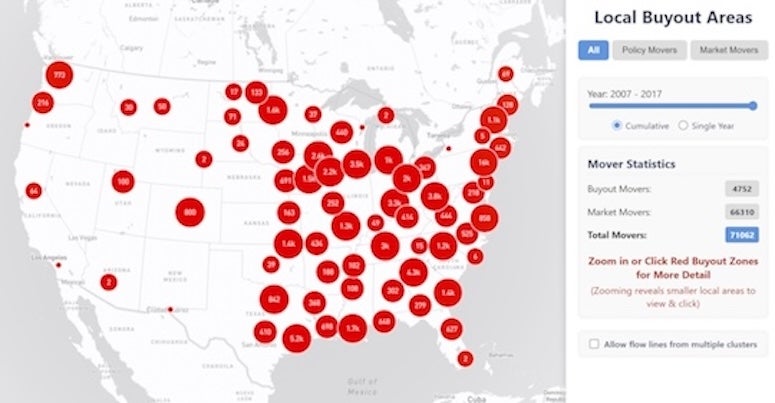

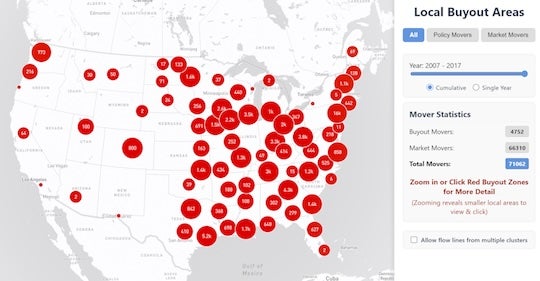

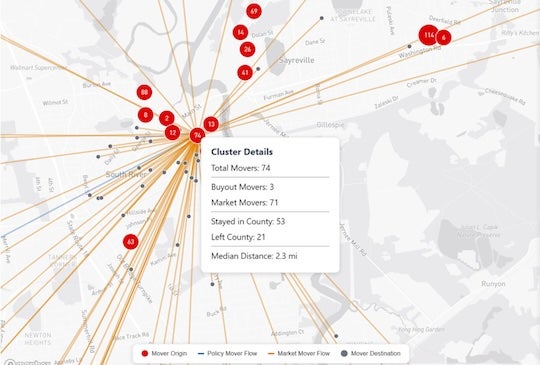

The FEMA buyout mapping tool, developed at Rice in partnership with data providers, offers the first national picture of how Americans relocate after the agency implements managed retreat in their community. The policy seeks to acquire and demolish homes in some of the nation’s most flood-prone areas, often after a recent disaster. The new tool tracks more than 73,000 Americans who moved from homes in more than 650 neighborhoods across 42 states following FEMA policy implementation. The map not only shows where buyout participants relocate but also tracks nearby neighbors who moved through conventional market sales or leases.

“What we found is the vast majority of people in these buyout zones are actually moving through what we might call the marketplace,” Elliott said. “They sell or rent their home on the market and pass the risk on to the next residents instead of having the property removed.”

Nationwide, the tool shows that for every one FEMA buyout and demolition, about 15 neighbors move away without federal support. “Some people are adapting by moving from growing flood risk,” Elliott said. “But that doesn’t mean the community as a whole is necessarily adapting. It could simply mean that others are moving into the flood-prone housing they’re leaving behind. As that happens, insurance rates can continue to increase, policies can be canceled and disaster recovery dollars can be spent repeatedly fixing up the same at-risk homes, drawing on taxpayer support at the federal and increasingly at the state level.”

FEMA’s program has purchased more than 45,000 homes across the country since its inception and invested billions of dollars, but the Rice tool suggests that the majority of retreat is happening outside federal programs — often invisibly, one household at a time.

The map also reveals a hopeful pattern: Most people don’t move far. The average relocation is just 5 to 12 miles from the original home, often within the same county. And according to hazard-risk ratings from First Street Foundation, the vast majority of these moves land families in homes that are at considerably lower risk of flooding.

“When they move, most people aren’t leaving the communities where they live,” Elliott said. “They’re staying close and getting safer with regard to future flood risk. That’s an important observation.”

Elliott said the tool can help communities and policymakers see the bigger picture. By combining FEMA records with residential location data and risk assessments, it provides evidence of how adaptation is actually happening and where federal programs could do more.

“The goal is to avoid a system where individuals solve their own problems by selling risky homes to others, leaving future buyers and communities to shoulder the consequences,” he said.

While FEMA’s focus has long been on floods, Elliott said the tool also has relevance for other hazards such as wildfires, mudslides and extreme heat. “It’s useful not just to people who are interested in flooding in the current program but also to those beginning to research and talk about climate adaptation in other contexts,” he said.

Elliott said the innovation offers a new way forward. “If we’re going to improve on these methods and help people — help ourselves — become more resilient to these climate challenges, we have to think not just about where experts predict risk but where people are actually moving when they begin adapting to it,” he said.

The interactive FEMA buyout mapping tool is now available on the CFAR website, and Elliott discusses the broader implications of this work in an article for “The Conversation.”