For Rice University senior Dasseny Arreola, pursuing two majors, one minor, three research fellowships and even a novel was never about checking boxes. It was about chasing the questions that mattered most to her and finding a community that encouraged her to keep asking. She credits the fellowships for helping her with that chase.

“I cannot overstate how instrumental humanities-focused fellowships have been to my journey in academic research — from providing a community in our cohorts to helping me learn what research can truly be in the first place,” Arreola said. “It’s only thanks to the generous support and funding that I have received during my time at Rice that I’ve been able to accomplish childhood dreams such as studying abroad at Oxford, and I’m incredibly grateful that these fellowships have allowed me to continue doing the things that I love in an impactful way.”

A double major in English and anthropology with a minor in ecology and evolutionary biology, Arreola represents the type of student the School of Humanities had in mind when it created initiatives like the Elizabeth Lee Moody Undergraduate Research Fellowship and the Humanities Research Center’s Carlson Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship or when the Office of Access and Institutional Excellence introduced the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship. These competitive programs not only give students the chance to conduct original research but also offer the funding, mentorship and community they need to think bigger about their work and its impact.

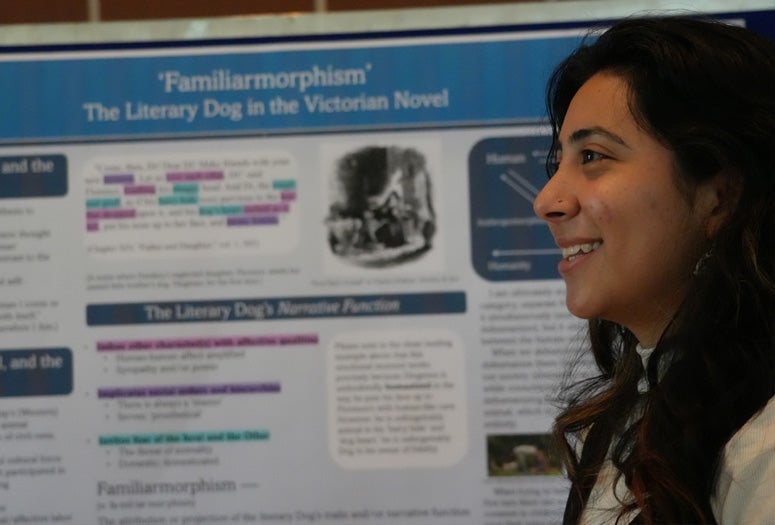

Arreola’s research blends Victorian literature with animal studies to explore how dogs were used to construct ideas of human identity and social order during the 19th century. Her project titled “Familiarmorphism: The Literary Dog in the Victorian Novel” challenges traditional humancentric readings of texts.

“My research, which has focused on how the dog transgresses human-animal boundaries in Victorian literature, uses the interdisciplinary field of animal studies to decenter the human in humanities,” Arreola said. “I think it’s an important example of how we can engage with already studied texts in new ways, and it participates in a school of thought that argues that the line of reasoning we use to justify human superiority over nonhuman animals is the same kind of reasoning we use to justify human-on-human discrimination. Animal studies, therefore, is paradoxically more revealing of ‘the human’ and sheds new light on the inner workings of contemporary human social issues.”

Arreola credits much of her growth to her faculty mentor Helena Michie, the Agnes Cullen Arnold Professor in Humanities, who saw the beginnings of the project come to life in her Victorian novel course.

“I almost did not include a class on sentimental dogs and the paintings of Sir Edwin Henry Lanseer in my Victorian novel class, but I did, and Dasseny was hooked,” Michie said.

Over the next two years, Arreola expanded the idea in multiple directions by blending posthumanist theory, visual art and close readings of 19th-century texts into a research project that rethinks the boundaries between species and social roles.

“While other people have written about attitudes towards dogs in the 19th century — especially about breeding and humane societies — Dasseny has contributed a highly original idea about the human character in novels that function as dogs and as loyal and sentimentalized supplements to human life,” Michie said.

Michie called the work “fresh, fun and exciting” and said watching it unfold over time was a privilege.

“I was lucky to have witnessed the initial spark of what was to become a passion project and a labor of love,” Michie said.

Through the support of Michie and her fellowships, Arreola has presented her findings at conferences hosted by Duke University, Johns Hopkins University and Rice and published a related article in the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal at Harvard University. Her research poster for Rice’s Humanities Days earlier this year offered a vivid look into her argument that dogs in Victorian novels were far more than loyal companions: They were symbolic figures through which larger questions of power, class and identity were explored.

“In true research fashion, I feel like my research can never be fully completed — there are just so many more avenues of inquiry that I still want to explore,” Arreola said. “I hope to continue this line of work beyond Rice, and I’d like to eventually move my survey of fiction beyond Eurocentric Victorian literature and perhaps someday even beyond dogs. The beauty of all research, though, is that we do not have to do this work alone, and we are always able to build off of each other.”

As she looks ahead, Arreola plans to take a gap year to further her studies independently before applying to doctoral programs in English literature.

“I also intend to complete the novel I’ve started writing here at Rice for my English capstone class with hopes of someday getting it published,” Arreola said.

For Arreola, the lessons learned through her project extend far beyond the pages of any novel.

“Humanities research has taught me that no question is too small, no subject too niche,” Arreola said. “It has shown me that the way we understand the world, even through something as seemingly simple as the figure of a dog, can have profound implications for how we see ourselves and each other.”