The human body stands at the center of “Figurative Histories,” a summer exhibition at Rice University’s Moody Center for the Arts, but it does not stand alone. Through color, texture, memory and vision, the exhibition invites viewers into an aesthetic dialogue that interrogates the stories we inherit and the ones we construct.

Featuring four Texas-based artists — Letitia Huckaby, Earlie Hudnall Jr., David McGee and Delita Martin — the show mines the personal and the political, illuminating how the body, and the Black body in particular, has served not only as subject but also as witness, archive and agent of resistance. Working across a range of media, each artist reflects on the conditions of historical exclusion while asserting the power of presence.

“As a research university at Rice, we’re interested in the ways our histories, both personal and collective, help us understand where we are in the present and perhaps imagine alternative futures,” said Alison Weaver, the Moody’s Suzanne Deal Booth Executive Director. “These four artists bring talents in photography, printmaking, watercolor and textile work and invite us to explore our own imaginations, our own histories and think about ways we might carry into the future what we inherit from our past.”

The exhibition’s point of entry is portraiture, an art form historically employed to immortalize a dominant point of view. At the Moody, it becomes a vehicle for reclamation. Hudnall’s black-and-white photographs bring documentary precision to bear on everyday life in Houston. His portraits reveal unguarded moments of joy, community and quiet dignity.

“They’re archetypes of my childhood — things that I remember, places I’ve gone, experiences that I’ve had,” Hudnall said. “It’s the universality of the human spirit: what we do, how we live, what our communities are like.”

The centerpiece of his installation is a photograph of the late Texas Southern University professor and debate coach Thomas Freeman beside a statue of Martin Luther King Jr. In that one image, Hudnall linked generations of influence.

“Dr. Freeman taught Dr. King early in his career,” Hudnall said. “I asked him to come with me to MacGregor Park, so I could take a picture of him standing by Dr. King’s statue, and he agreed. That’s the image I made.”

Huckaby’s portraits printed onto cotton fabric are rooted in acts of remembrance. The subjects are descendants of Charlie and Kate Thorpe, who labored at Texas Christian University in the late 19th century when it was located in Thorpe Springs.

“When I was hired to create portraits to honor the Thorpes, I decided to photograph their descendants who worked at TCU,” Huckaby said, explaining that there were no existing images of the couple. “I hope that I am taking everyday people and presenting them in the way you would expect to see in an old master painting.”

Huckaby described “Figurative Histories” as “a conversation in color and texture.” Throughout the exhibition, a shared visual, conceptual and historical language unfolds with poignant coherence.

“When you walk in and you see a conversation happening visually, it’s just really exciting,” Huckaby said.

That conversation continues in the layered images of Martin, whose mixed media works center Black women.

“I work in layers, but those layers reference history, reference time,” Martin said. “They speak about the complexity of these women as human beings.”

Martin said she views her role not only as an artist but as a cultural interlocutor.

“We are here as artists, and we are offering a glimpse into our communities, into our worlds, into our minds, but the viewer is equally important,” Martin said. “When the viewer can look at my work and identify with a figure or symbol in the work, a conversation has started. And at that point, as the artist, I have done my duty.”

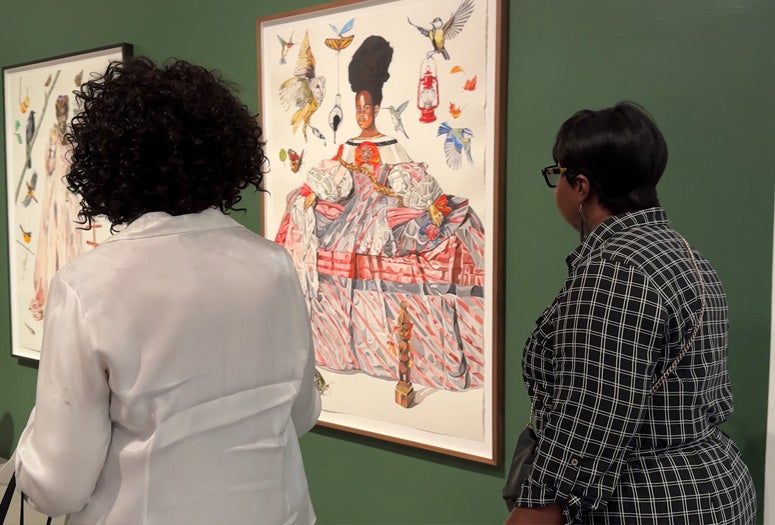

McGee’s watercolors evoke an entirely different visual register. Their scale and fragility demand attention, even as their subject matter — figures in period dress surrounded by weightless symbols and icons sited in imagined spaces — resist easy interpretation.

“These paintings are about the reconstructive power of the imagination, the reexamining of the imagination, the deconstruction of art history, the power of women and the power of freedom,” McGee said.

Working in watercolor, McGee said, requires precision and trust.

“It doesn’t allow second chances,” McGee said. “It forces you to slow down. One mark is the mark. It’s like reductive printmaking; you have to think before you make every mark.”

Despite their varied methods and media, each artist channels memory and imagination as tools of resistance and reclamation in “Figurative Histories.” Their work underscores the richness of individual experience as well as the generative potential of collective storytelling.

“This exhibition is about humanity,” McGee said. “It’s about the power of that negotiated space we find ourselves in where we’re holding ourselves captive by other people’s expectations and not living our lives. Art can help you free yourself from that if you’re brave enough to participate in it.”

Visitors can explore the exhibition’s visual narratives alongside a curated playlist, reading room and interactive installations. Learn more about “Figurative Histories” here.