With a historian’s eye for the telling moment, Douglas Brinkley paused midway through his National Heritage Lecture to recall Theodore Roosevelt’s command at the rim of the Grand Canyon — a line that captured the essence of his argument on presidential power.

“‘Do not touch it. God has made it. You only mar it. Leave the Grand Canyon alone,’” Brinkley said, repeating Roosevelt’s words.

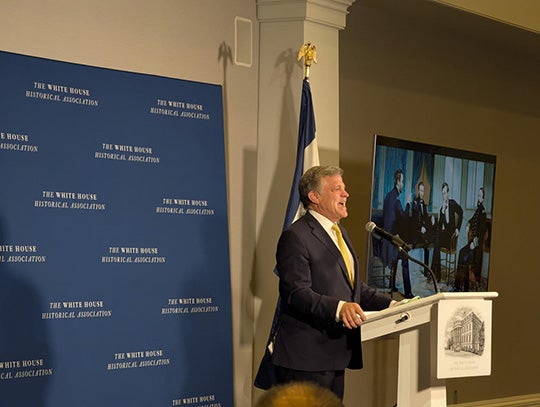

A leading presidential historian and the Katherine Tsanoff Brown Professor in Humanities at Rice University, Brinkley delivered the 2025 National Heritage Lecture at Decatur House in Washington D.C. Oct. 9, a prestigious program hosted by the White House Historical Association in partnership with the U.S. Capitol Historical Society and the Supreme Court Historical Society. His address “Presidential Evolution: A History of Executive Orders Over 47 Presidencies” charted how American presidents have used executive orders to manage crises, conserve lands, wage wars, reorganize government and increasingly to bypass gridlock on Capitol Hill.

The Grand Canyon anecdote anchored his portrait of Roosevelt as a turning point. Roosevelt, Brinkley said, applied the 1906 Antiquities Act “elastic” authority to lock up not acres but landscapes then let the courts validate his reach.

In the lecture, Brinkley moved briskly across two and a half centuries. Early presidents largely used orders for routine administration. Lincoln made the instrument consequential with the Emancipation Proclamation, a wartime act that previewed how later presidents would claim urgency to act first and justify later. Ulysses S. Grant wielded orders during Reconstruction. Woodrow Wilson used them to censor communications and entrench segregation within the federal workforce. Franklin D. Roosevelt then transformed executive orders into an engine of governance during the New Deal and World War II from the Civilian Conservation Corps to the Manhattan Project — and infamously the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans.

“‘I’ll throw everything against the wall and see what sticks,’” said Brinkley, repeating a line he noted captured FDR’s method: push dozens of directives at once, accept that courts will swat down some and move fast enough that the ones that “stick” reset expectations about presidential authority.

The results built public works from LaGuardia Airport to the San Antonio River Walk while also exposing the dangers of speed and unilateralism when fear and prejudice fill the vacuum.

Brinkley framed the modern era as a cycle of assertion and reversal. Presidents increasingly govern by pen on issues from public lands to immigration to civil rights, and the next administration often rescinds, revises or replaces its predecessor’s orders. The pace, Brinkley said, is enabled by technology and political polarization. The spectacle of Day 1 signing ceremonies has turned unilateral action into ritual.

“We are living in the time of peak presidential power built on a Constitution that doesn’t have clarity of executive prerogative,” Brinkley said. “We are living in an America where executive orders are becoming the norm of presidential behavior. … We’re getting to a point where executive orders are being filmed every day with a big camera, big signatures and people watching it as if it’s a sporting event.”

Brinkley noted that executive orders are fast and visible for supporters yet are neither legislation nor final, often triggering checks and balances in courts, in agencies and at times at the ballot box while steadily diminishing Congress’ habit of legislating.

The lecture also underscored the civic stakes of definitions. Brinkley distinguished between ceremonial proclamations and legally operative orders aimed at directing the executive branch. He pointed to moments when emergency framing has expanded presidential latitude from Lincoln’s wartime measures to homeland security after 9/11. Emergencies demand speed, Brinkley acknowledged, yet the rhetoric of emergency can become a habit that rationalizes executive shortcuts beyond genuine crisis.

If FDR embodied maximalism, Theodore Roosevelt supplied the template. Brinkley lingered on the number of orders — from Washington’s eight to Theodore Roosevelt’s 1,081 — to show how precedent plus litigation can become policy. When courts uphold expansive readings, future presidents rarely forget.

“It’s the federal government and the Army now saying, ‘You’re nothing separate. You’re an American,’” Brinkley said.

That line delivered in a discussion of Harry Truman’s 1948 desegregation of the U.S. military demonstrated executive orders at their best: using federal authority to accelerate equality when Congress wouldn’t. Brinkley balanced that with the hard lessons of executive order 9,066 in 1942, which resulted in Japanese American incarceration camps and serves as a reminder that unreviewed speed can trample rights.

The National Heritage Lecture is among Washington’s most respected civic forums, hosted by the White House Historical Association in partnership with organizations devoted to preserving the legacies of the presidency, the Capitol and the Supreme Court. Brinkley’s invitation to deliver this year’s address places him within a distinguished tradition of historians asked to illuminate the American experiment through the lens of government itself.

“People will believe it’s the law because an executive order was just signed, when in truth it’s usually the beginning of an arduous legal process,” Brinkley said.

The lecture’s closing message was one of vigilance, not alarm. Executive orders, Brinkley suggested, remain essential instruments of governance but also reminders of the balance democracy requires. The fastest path, he warned, is rarely the firmest — and the nation’s health depends on laws built to last, not only on signatures written in haste.