Deep in the heart of Tanzania’s Udzungwa Mountains, a trio of Rice University researchers — ecophysiologist Andrea Rummel, graduate student Annie Finneran and junior Caroline Pollan — embarked on an ambitious summer field study to understand how human impacts are reshaping forest ecosystems. Armed with bat detectors, camera traps, soil sampling kits and a passion for ecological discovery, they worked alongside Tanzanian scientists to track the interplay between biodiversity, conservation and nutrient cycling in one of Africa’s most biologically rich yet vulnerable landscapes.

The project was rooted in a deceptively simple question: How does human activity, especially hunting, alter which animals live in a forest and what happens to the land as a result?

“We had this rare opportunity to study two forested sites side by side,” said Rummel, assistant professor of biosciences. “One is a well-protected national park, almost pristine. The other, just over 100 kilometers away through connected mountainous forest, is heavily poached. It’s an ideal natural experiment to ask how these different management strategies affect both the animals and the ecosystem itself.”

Finneran, a doctoral student in the lab of assistant professor of biosciences Matthew McCary, spearheaded the project, which forms the final chapter of her dissertation. Her research combines camera traps and soil analyses to explore what happens when large mammals — primates especially — disappear due to hunting.

“Primates are a major target for poaching in the unprotected forest,” Finneran said. “That changes not only the animal community but also the way nutrients cycle through the ecosystem. Different species excrete different nutrients at different rates. So when some vanish, it alters the chemical makeup of the soil and potentially the whole forest’s health.”

Finneran worked with local collaborators Arafat Mtui and Steven Shinyambala from Mazingira Alliance for Community and Conservation at the Udzungwa Ecological Monitoring Centre to set up a series of camera traps in both the protected and unprotected forests to monitor which mammals are present. At the same sites, she collected soil and vegetation samples to measure nutrient levels like nitrogen and phosphorus — data she said she hopes to later feed into a computer model to simulate long-term ecosystem shifts.

Alongside this focus on the ground, Pollan took to the skies — figuratively speaking — to track bats. Double-majoring in ecology and visual arts, Pollan designed her own research project through Rice’s Wagoner Scholarship, which provides up to $15,000 for undergraduates to conduct international research.

“Bats are amazing creatures to study,” Pollan said. “They’re the only mammals that can fly, and they play critical roles in ecosystems worldwide.”

Working with Rummel, who studies animal locomotion and thermal physiology, Pollan deployed bioacoustic monitors called AudioMoths to record ultrasonic echolocation calls from bats across both forests.

“We placed six detectors in each forest, pairing them with the camera trap locations,” Rummel said. “It’s passive data collection — we just let the monitors listen, then analyze the calls later to determine which species are present and how active they are.”

To supplement the recordings, Rummel and Pollan also mist-netted live bats and recorded their calls in hand, building a reference library of local species to aid in analysis.

“This region is really understudied in terms of bats,” Pollan said. “We might even have recorded species that haven’t been well documented here. I can’t wait to dig into the data this fall.”

The fieldwork was rigorous, involving long hikes through steep, mist-shrouded terrain. But the researchers say the scientific collaboration and forthcoming insights make it all worthwhile.

“I spent a year and a half designing this project, getting permits, applying for funding and coordinating logistics,” Finneran said. “But our collaboration with Tanzanian scientists was essential. They’ve been monitoring this area for over a decade, and they helped ensure our work would be useful long-term — not just for our own papers but for local conservation planning.”

Finneran said one of her goals is to leave a legacy of ongoing monitoring. Soil samples are being analyzed at a nearby Tanzanian university, and local field teams are continuing data collection.

“It’s not just about producing cool science,” she said. “It’s about supporting efforts to use conservation as a tool for both ecological health and economic opportunity.”

Domestic tourism is growing in Tanzania, and preserving biodiversity could boost the local economy. As Finneran put it: “The more data we have showing the impact of poaching and the benefits of protection, the stronger the case for investing in conservation.”

For Pollan, the experience was both scientific and deeply personal.

“Going to Tanzania twice as an undergrad, once through a class and now for research, has been life-changing,” Pollan said. “I’m definitely going to pursue a Ph.D. in ecology and evolution, but I’m still figuring out what I want to specialize in.”

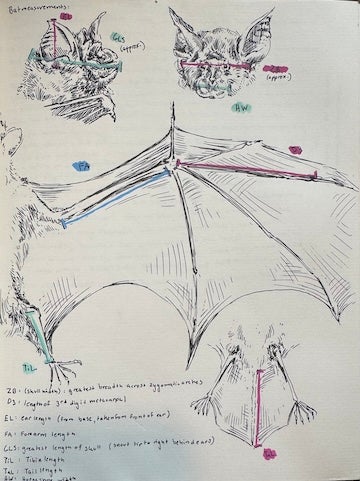

In the meantime, she continues to merge her scientific curiosity with her artistic talent. While in Tanzania, she drew detailed illustrations in her notebook alongside observations and learnings from the field, creating a piece of art that blends science with storytelling.

“It’s rare to find a place like Rice that supports this kind of undergraduate involvement,” Rummel said. “Caroline came up with her own question, designed the study and executed it beautifully. Experiences like this can truly shape a career.”