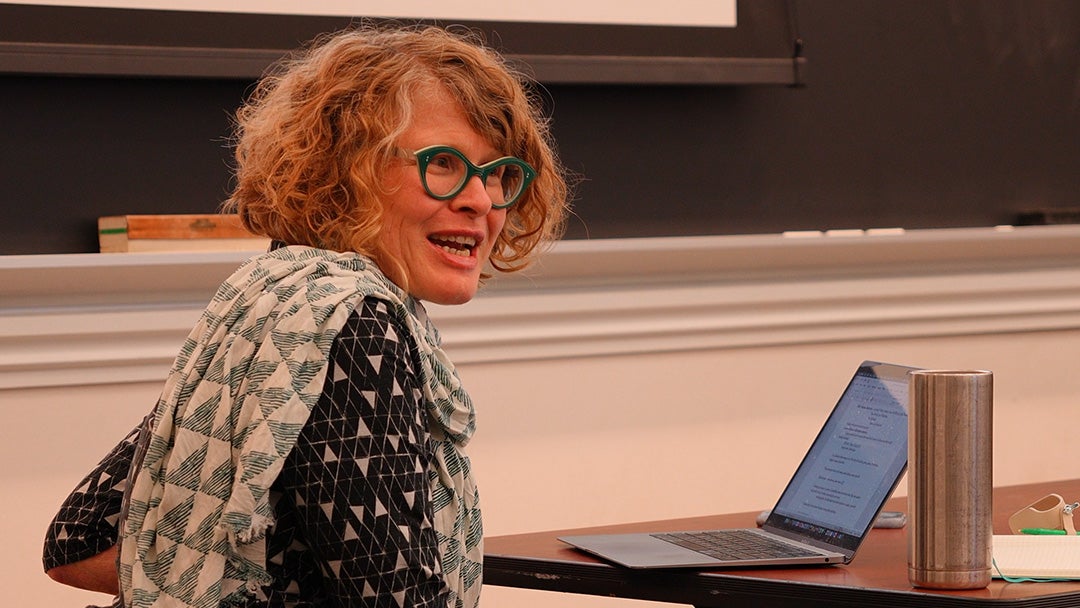

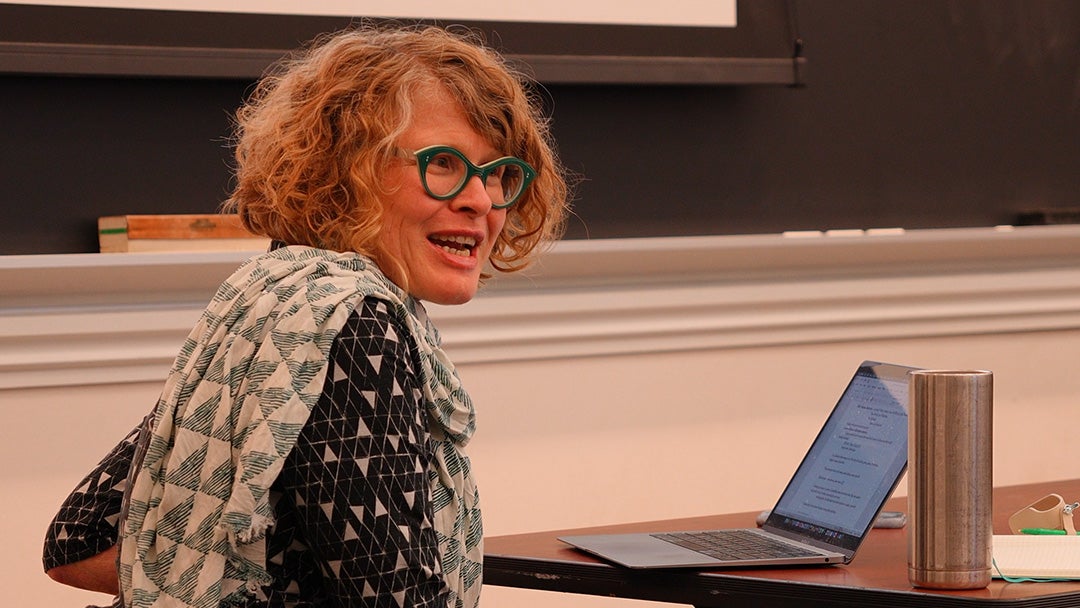

As debate over reproductive rights ramps up in the aftermath of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization 2022 ruling, University of Texas at Austin professor Alison Kafer visited Rice University March 19 to present the 2024 Women’s History Month Lecture: “Disability and Reproductive Justice.” Sponsored by Rice’s Department of History and Center for the Study of Women, Gender and Sexuality with support from the dean of humanities, Kafer’s lecture urged a reexamination of current approaches through the lens of disability studies and justice.

“Disability is not really being talked about in terms of the impact of the fall of Dobbs, and there’s very little attention to the way it impacts disabled people in particular,” said Kafer, UT’s director of LGBTQ studies, the Embrey Associate Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies and associate professor of English. “The disproportionate impact of abortion bans and restrictions on sick and disabled people was true before Dobbs before the end of Roe v. Wade, but it’s even more true now.”

Kafer made it clear that any conversation about reproductive rights or reproductive justice should revolve around more than just abortion access.

“Disabled people face many barriers to reproductive health care in the U.S., and attributions of disability are often used to justify interventions into people’s sexual and family lives,” Kafer said. “While ideas about disability have played a central role in debates about abortion, the ways in which disabled people are themselves affected by abortion restrictions have received far less critical and political attention.”

She attributed the lack of attention in part to a cultural reluctance to acknowledge that people with disabilities have sexual lives.

“Disabled people get pregnant. They get pregnant on purpose. They get pregnant accidentally. They get pregnant coercively, forcibly,” Kafer said, adding that another issue is a lack of sex education. “People who have intellectual disability labels are not given the same kind of information about contraceptive options that other people are.”

Instead of having a conversation about contraception, sterilization is an all-too-frequent alternative. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, for example, ruled before his SCOTUS appointment that he supported the sterilization of people with mental disabilities even if it was against their will.

“Thinking about the history of sterilization, it’s important for us to remember that it’s an ongoing history for marginalized groups in the United States,” Kafer said.

In Texas where lawmakers adopted Senate Bill 8, which bans abortions as early as five weeks after a patient’s last menstrual cycle and delegates the responsibility of enforcement to its own citizens, Kafer predicted a “mass disabling event.”

“(The law) disproportionately restricts the reproductive rights of people with heritable disabilities,” Kafer said. “Someone with a disability that might be passed on is more likely to be caught up in these bans, so here we go again.”

That argument is being used to fight abortion bans, which generates a new round of concerns related to how people with disabilities are involved in the conversation about access.

“When we force women living in an ableist culture to prove that their abortions are ‘justifiable,’ disability remains a convenient and effective justification for preserving at least a minimal right to abortion,” Kafer cited from her 2013 book “Feminist, Queer, Crip.” “Making disability do the work of defending abortion may be effective in securing abortion rights in the short term, but it does so by trafficking in discriminatory stereotypes about disability. Moreover, its long-term effectiveness is doubtful as it opens the door to a continued interrogation of individual women’s reasons and decisions.”

Kafer also pointed out that people with disabilities experience disproportionate exposure to sexual violence.

“It is often the person who provides care for them who is the abuser, which can make accessing abortion care even more difficult,” Kafer said.

That care is also imperative for people who are taking medications for their condition that may be counter-indicative to pregnancy. Kafer suggested health care is a concern in general for people with disabilities in a post-Dobbs/SB 8 Texas.

“Many chronic illnesses make pregnancy more complicated or risky, so anything that pushes those folks into pregnancy can become life threatening or debilitating,” Kafer said.

People with disabilities can have a fraught relationship with health care due to the way medical providers can deny or remove care. Health care sites can be linked to marginalization or violence, while SB 8 adds a layer of surveillance from providers who could report patients seeking an abortion to the state.

“Thinking about abortion as health care, as the solution to the problem, I think is tricky in ways that I haven’t really figured out how to parse,” Kafer said.

What data has been collected, which isn’t much according to Kafer, suggests Texans with disabilities are not seeking out-of-state abortions at the same rate as their peers. The cost of travel along with serious medical concerns and limited health care access has led to them being labeled a “missing population.”

Kafer quoted Charlie Hughes, the intake director for the Texas Equal Access Fund, who said it was very difficult for disabled Texans to access care when it was close by. Now it just seems “impossible.”

To the dozens of students and faculty present for her lecture, Kafer closed with a question: “What can disability studies, justice and the right lenses help us do differently?”