Full coverage of Rice at the 2024 Olympics

As the 2024 Paris Olympics draw to a close, the final week marks the end of an inspiring chapter for Olympic athletes.

Many Olympians, while proudly representing their countries with incredible performances, are also representing universities as they jump, run, swim or throw their way to glory. This is something three-time Olympian and former Rice University standout Rosey Edeh knows well.

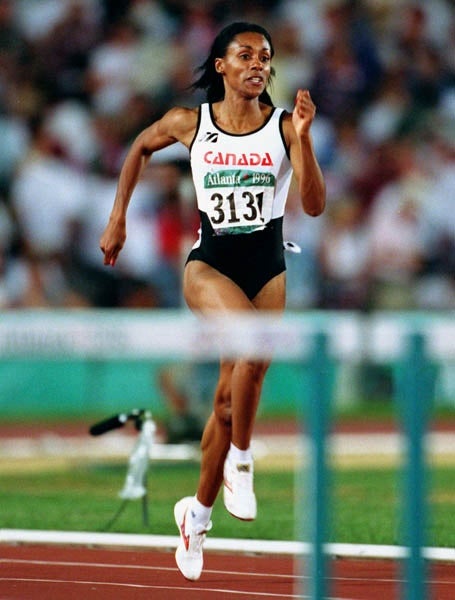

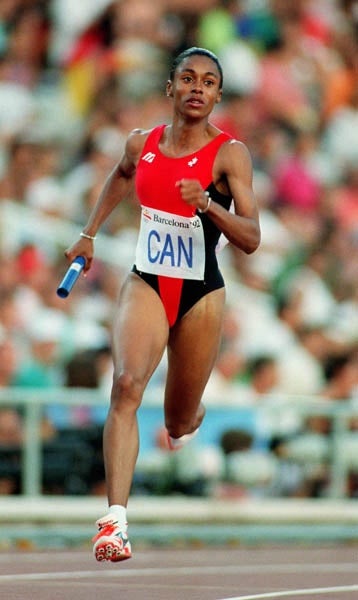

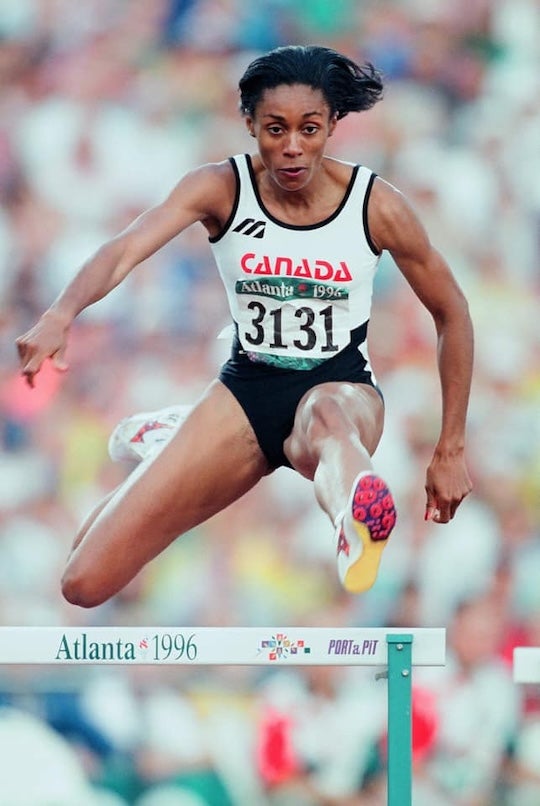

Born in London, Edeh grew up to become a world-class 400-meter hurdler, representing Canada in the 1988, 1992 and 1996 Olympic Games after being named an All-American in track and field four times at Rice. Recognized as one of Rice’s finest athletes, she was inducted into the Rice Athletics Hall of Fame in 1996.

In the 400 hurdles final at the 1996 Summer Olympics, Edeh set a Canadian national record that stood over 23 years.

She used her experience in athletics to become a widely recognized television personality as a sports reporter, weather specialist, entertainment reporter and a senior news anchor.

Building on her vast experience as a broadcaster as seen on CNN, MSNBC and Global News, Edeh produced and directed the award-winning film “Oliver Jones: Mind Hands Heart” (2017).

Currently the host on “CTV Morning Live Ottawa,” Edeh discusses the latest news and offers a fresh new perspective on life in the capital with Rosey’s Roundup.

In July 2016, her daughter Micha Powell was named to Canada’s Olympic team as an alternate.

To get an idea of what it’s like to compete at the highest level at a record-breaking pace, as well as what it’s like to watch others do the same, Rice News had a conversation with Edeh:

What is it like watching the Olympics as someone who competed in the world games?

“A few years after I finished competing, I didn’t really even look at track to be honest with you. It felt very weird to not be on the track. It didn’t feel normal to be sitting in the stands watching other people run. Then I slowly started to find myself back in the world of athletics. I got invited to be an infield reporter or commentator, and then I said, ‘Oh, OK, enough time has passed. I kind of like this again.’

“Then my daughter developed an interest in track and field and asked me, ‘Hey, Mom, can you time me? I want to run 100 meters.’ And we have a track right beside us. That was just after watching Usain Bolt tear up the track in the 2012 Olympic Games. So she developed a love for track and ran track in her last year of high school, then she got a scholarship and went to school at the University of Maryland and kept running and running. That’s how I got back into track because I’m cheering on my daughter and going to track meets, and I just fell in love with it all over again through her.

“It’s really enjoyable to get back into the sport on different levels — as a mom, as a coach and as a writer and reporter of athletics. I thoroughly love this sport, and standing back, I just realize how much track has taught me and how it has molded me as a human being.”

Tell me a bit about your upbringing and how you got into track and field.

“In elementary school in Canada, we had that participation and physical fitness award system where you do a bunch of different events throughout the school year, and if you score high enough, you get the award of excellence. I was like, ‘I don’t want no bronze, no silver, no gold. I’m going for the top.’ And I was just highly competitive. I knew that I wanted that badge, so that innate, competitive drive is something that was always there.

“My mom and dad were sporty but not from a national team perspective. Growing up, they worked. And my mom at one point said, ‘OK, you kids have to find something to do after school, you can’t just hang around the house.’ So track and field, unlike team sports where you have to try out and hope that you make it, track and field you just have to show up. You come run and they’ll put you in an event, so that’s how I got involved in track and field. Then I just kept running.

“I joined a track club in Canada and had success pretty early. It wasn’t Earth-shattering success where I was breaking records, but it was enough to keep me interested. Then on my first national team, I got to go to Japan, and that was a really positive experience. I went, ‘Whoa, I never would be able to go to Japan just as a kid on my own, so this is kind of cool.’ Then it was just steady success and always working hard. I ended up in Houston, Texas, and I can’t emphasize enough just how groundbreaking that was for me and how life-altering that was for me to go to Rice University.”

How do you remember your time at Rice, and how did it help prepare you for the Olympics?

“Stepping on campus at Rice, it was like, ‘This isn’t real, is it? This is so beautiful.’ And then really vibing with some of the teachers who I reached out to from time to time years after I graduated like Dr. Steven Tyler, may he rest in peace, a professor of anthropology. I made the Olympic team in 1988 — that was my first Olympic Games. I knew that I would be late returning to school, and he gave me an assignment that I could do while I was in Korea, and it was wonderful because I had enough time to do some research. I came back and wrote the paper and got an A, by the way. But I’ll never forget that. He gave me a little bit of space to perform this research and allowed me to do some supplemental work, and I was able to fulfill my Olympic dreams. That was amazing because the synergy between Rice University and my athletic goals really blended quite well, and both really bolstered the other. My desire to perform well academically fed into me performing well athletically, so I could keep my scholarship. It gave me a sense of pride to come back to Rice University and go ‘Yeah, I’m an Olympian.’

“Rice played a big role in preparing me actually, because my coach was the head coach of the women’s program at Rice University — the great Victor Lopez. And Victor Lopez was so well respected around the world. Rice University had the wherewithal to employ such an incredible coach, such an incredible academic and intellectual, especially when it comes to the world of biomechanics, sprinting, periodization and getting yourself ready for that optimal performance at the optimal time. Victor advocated for us, and he made sure that we knew what the university would demand of us academically, and he demanded just the same athletically. It came together very well. And I did feel a certain sense of pride that I knew that the university was behind me, and I knew that if I perform well, I’m performing well for the university.”

What was your experience like in the Olympics?

“The first thing that comes to mind is ‘strong mind.’ I think that if a purple flying pig flew by me on my way to the 400-meter hurdles final, I probably wouldn’t have even batted an eye. I went to three Olympic Games. My first one, I was kind of like the movie Russell Crowe in ‘Gladiator’ when he first walked into the Coliseum was like, ‘Whoa, what’s happening?’ Then the next Olympic Games I came in fourth in the 4x4 relay.

“If you look at people on the podium when they got gold, silver and bronze, the gold medalist has the biggest smile. The second biggest smile is the bronze medalist because they’re just happy to make it onto the podium. Silver medalist is like, ‘Dang, I just missed gold.’ Then the people who are off the podium in fourth place are probably the most miserable people out there because they didn’t even get on the podium, and that was me and my other teammates in the 4x4 relay. It was very sad, but that got me hungry. So I made it to the ’96 Olympics after having my daughter and after being told, ‘You don’t have enough time. Mothers never make it to the Olympics. What are you talking about? How can you be a mom and run track at that level?’ Yeah, watch me.

“So the main goal in the ’96 Olympics was to run faster than I’ve ever run before. And I did it in the semifinals and in the finals. I came in sixth and ran a Canadian record. I proved to myself that I could do it even though I did have a lot of naysayers. But once again, that whole concept of having a strong mindset: That’s what I remember most and that’s what I take away from my Olympic experience because there’s so many things that happen and so many distractions and to perform at your best is really quite remarkable. That’s what I was able to do both in ’92 and ’96.”

How do you feel like the Olympics molded you as a person after that experience?

“I learned to walk real tall. When you get the opportunity to represent your country, you realize that you’ve just accepted a great responsibility. And when you walk into the Olympic Games, opening ceremonies and you’re wearing your country’s colors, make no mistake about it: You’re a representative of your country, and it’s a big deal. You cannot walk in there small. My Olympic experience has taught me to walk really tall and to know my worth. And sometimes it’s a deeply embedded thing, but it’s there. That tall walk represents all those years of hard work and the fruits of my labor.”

How much does it mean to you to be an Olympian, representing not only Canada but also Rice?

“When you get to the Olympic Games and become an Olympian, you’re always an Olympian. You’re not an ex-Olympian or a former Olympian. That’s always a part of you. And it’s exactly the same thing when you walk onto the campus of Rice University. And when you walk off campus and graduate, you realize you’ve accomplished something so big, and you’re a part of a family that will never leave you. You’re always going to be a part of the Rice family. I was at Rice visiting just before the pandemic in 2019, and you walk on campus and you’re like, ‘I’m home again.’ I take with me everywhere that I’m an Olympian and I’m a Rice U. graduate. I’m a Rice Owl, always. It’s about that pride, and it’s about knowing that there are so few people who can accomplish what I have accomplished.”

What would you say was the hardest part about being an Olympian, and what was your favorite part?

“The hardest part about being an Olympian is the anticipation and the buildup to your very first race, because sometimes it kind of wakes you up and then you have a bit of a panic attack or the butterflies, and you just cannot wait to get out there. But you’ve got to calm yourself down, and you’ve got to wait, because your race will be when your race will be. It’s 120 days until the Olympic trials, because you’re not even sure you’re going to be on the Olympic team. And then you make the Olympic team, and you’ve got to wait to get on the track to run in the heat. The most nerve-wracking time is that first race on the Olympic track. You’ve got to find a way to control your nerves to calm yourself down yet build yourself up to get out there and apply the proper intensity to your training, so you can indeed get faster and improve and be ready to peak at the Olympic Games. So it’s all about that anticipation and mitigating all of that stress — just bottling it and then using it when you finally get out there to run.

“And I think that the best part about the Olympic experience is whether you won a medal, whether you were running a world record or you’ve run a national record, or if you’ve gone out there and you competed to the best of your abilities, every single time you cross the line and look up, you realize ‘I did it.’ And there’s nothing like it. I didn’t even win a medal, but people thought I had won everything because I was so absolutely elated. And it’s a great example of: Who cares what other people are doing? I know what I need to do. And I really did stay in my lane, figuratively and actually. I stayed in my lane and I took care of me. There is something so wonderful about knowing that you put yourself first, and you took care of the task at hand. It’s an incredible feeling.”

What was your most memorable experience from the Olympics?

“It’s a crazy moment. I don’t know how it happened, but in 1996 — my last Olympic Games — my daughter was just over a year old. I raced the finals, came in sixth, ran a Canadian record, ran the race of my life and had to do a number of interviews right after the race on the runway. You’re talking to reporter after reporter, and then I walk up and oh, there’s my daughter with my mother. How on Earth did she get there? She handed me my daughter, and I was like, ‘OK, I’m a mom again.’ And I took her to the warm-down area, and then I went to do more interviews, and she was just with me the whole time. I’m not really even sure how I got her back to my mother after that. It was a bit of a blur. But that was pretty unforgettable to have her with me right after I ran and share that moment with her. I don’t know how my mother did it. Thank you, Mom … that was amazing.”

You’ve talked about how the Olympics molded you and your passion for track and field. How do you carry that passion today and use it in your current roles?

“Well, I don’t know if people can see me doing it. But the Olympic experience is so intense. There’s so much pressure. There’s outward pressure and there’s inner pressure, and it comes from everywhere. It’s the athlete’s duty to harness the pressure instead of allowing the pressure to take over you. Sometimes you’ll see athletes kind of repeating a mantra, talking to themselves like ‘OK, you got this, you’ve got this.’ And then they explode and go swim an Olympic record or they run, jump, throw or whatever it is. So that’s a little secret weapon that I’ve taken with me from the Olympic Games. Most of the situations that you find yourself in after the Olympics are not going to be anywhere near as intense, but there are still some pressures in life that you have to talk yourself up for. So I apply that mindset, and I’m not even sure if my lips move when I do it. But I tell myself a mantra like ‘you got this’ if I’m going live or breaking news live and it’s a very intense moment, because breaking news can be very stressful as well. Sometimes, I’m not sure if it’s in my head or if I’m actually saying it out loud, but I don’t care because I know that what works for me is that strong mindset and just not to panic.”