by Jade Boyd

Special to Rice News

Rice University astronomer Andrea Isella and colleagues have reported the first observations of gaseous water in the portion of a protoplanetary disk where a rocky, Earth-like planet might be forming around a distant star.

Published in Nature Astronomy, the discovery is an important demonstration that water in the habitable zones of young stars can be viewed by telescopes on Earth. Study co-authors included Rice graduate student Ramon Wrzosek and lead author Stefano Facchini of the University of Milan.

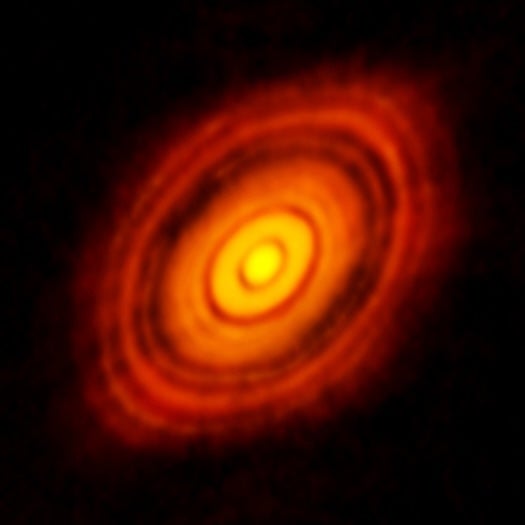

The researchers found water in a region of the inner disk of star HL Tauri where a planet may be forming. The star is smaller than the sun and about 450 light years from Earth. The discovery was made with observational data collected more than two years ago with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a facility in Chile that has 66 radio telescopes fanned out over nearly 100 square miles of an plateau more three miles above sea level.

Isella’s role was comparing data from observations and theoretical models to arrive at the total estimate of water — about three times more than all the water in Earth’s oceans — in the observed portion of the disk. He said the process was complicated because only a fraction of the water in HL Tauri’s inner disk emitted the frequency of light that the team observed from ALMA.

“We only see water that is in the gas phase and only at a particular temperature,” he said. “There is more water in the gas phase that we do not see. There’s water frozen out on dust grains that we do not see. The only way to find out how much water you actually have is to compare with a theoretical model.

“In the paper, we did a simple analysis,” Isella said. “Now, we are working on doing a more sophisticated analysis that will give a more precise estimate.”

Astronomers have long searched for water in the inner regions of disks of dust and gas where planets form around young stars. It is relatively easy to see water that is very hot and close to a star, but observing warm water vapor is especially difficult because water vapor is so plentiful in Earth’s atmosphere that it typically drowns out the faint signal from distant objects. ALMA’s telescopes are above most of the water in Earth’s atmosphere, but Isella said the researchers also needed some luck, in the form of extraordinarily clear weather, to observe water around HL Tauri.

Now that they know water can be observed from ALMA, the stage is set for gathering more and more detailed data in the future.

“Now that we know that there is an emission, we can take a higher definition image and better understand where the water is coming from and where the snow line is,” Isella said, referring to the distance from the star where water freezes, which is an important factor in planet formation.

“We have some idea of where this line is based on the model we have been running here,” he said. “But there are complications. Water is a very messy molecule. Having more observational data will lead to better models and improved estimates.”