Newborns in the Dominican Republic with severe abdominal distention don’t face the same odds of survival as those born in the U.S.

A team of Rice University engineering students put their skills to work toward closing this health care gap.

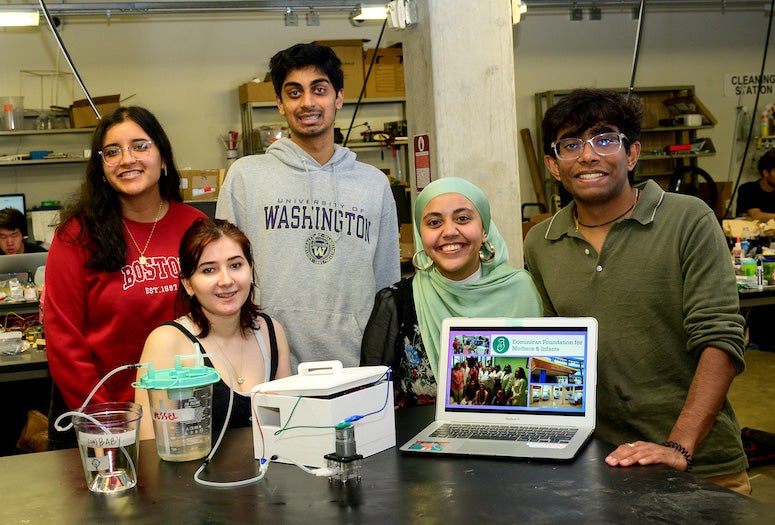

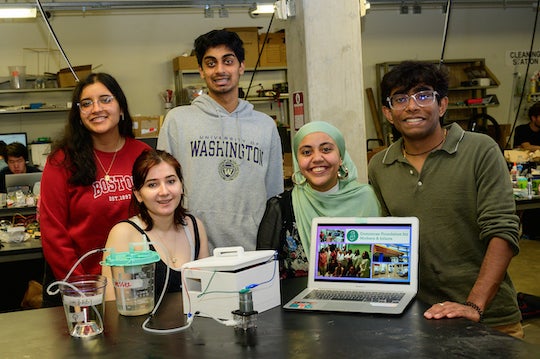

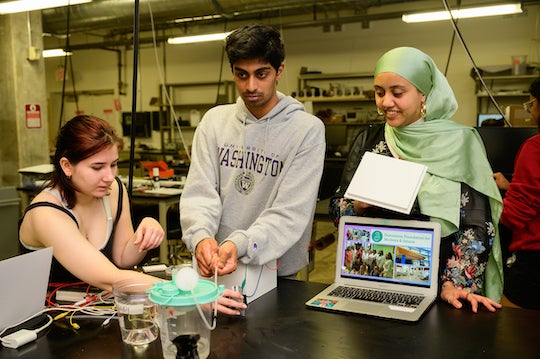

The BellyTubbies team — Pavithr Goli, Ajay Kumar, Ana Saucedo, Summer Shabana and Anna Tutuianu — partnered with the Dominican Foundation for Mothers and Infants to design a gastric suction device tailored to the specific needs and health care environment of the Hospital Materno Infantil San Lorenzo de los Mina, one of the largest maternity hospitals in the Dominican Republic.

One of the diseases that can cause abdominal distention and requires gastric suction is necrotizing enterocolitis, a life-threatening condition caused by bacteria that affects the gastrointestinal tract of babies. Treatment involves intubation, antibiotics and gastric suctioning to prevent sepsis and organ damage — and in the Dominican Republic, the necessary infrastructure is absent.

“Most hospitals in the U.S. have their own medical gas and vacuum supply lines,” Tutuianu said. “In a U.S. operating room or a neonatal intensive care unit, there would already be a vacuum line that doctors can use to suction out excess fluids.”

Portable suction devices used in emergency care settings in the U.S., on the other hand, are both too expensive and incompatible with the power grid in the Dominican Republic.

Alternative gastric suction treatment methods are less effective and place a high burden on health care personnel.

“Our sponsors from the Dominican Republic talked to us about two common methods that are used in place of an actual suction device,” Goli said. “A nurse or a doctor would use a syringe connected to a tube implanted into the baby’s stomach to remove excess fluid. This is not really an effective method because it requires that someone be there constantly performing this task or else risk fluid buildup, which can lead to asphyxiation, etc.

“Another method uses a siphon and relies on gravity to remove excess fluid. This method is also not very effective because suctioning can stop at any time and it’s difficult to get it to run continuously. This method also requires manual operation, which is not ideal in a busy hospital setting.”

The device the team built is designed to suction intermittently in order to avoid the drainage tube getting stuck to the gastrointestinal tract wall. The suction intervals were programmed based on data provided by the sponsors.

“Not only do you use a specific gastric suction tube, but you also oscillate the suction pressure,” Tutuianu said. “The suction should not be constant, but rather occur at intervals of maybe seven to 10 seconds, with pauses of 15 seconds. A baby's stomach is unique in that you don't actually need to generate as much pressure as you might on an adult. We're really only operating within low-pressure parameters.”

Students envision their device being streamlined into an even smaller, more compact prototype.

The project was one of over 110 in this year’s Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen showcase and competition — recently renamed the Huff OEDK Engineering Design Showcase — which was held April 13 at the Ion. BellyTubbies is also a finalist in the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs student design competition, which promotes interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation in medical device technology.

The team was mentored by Jasmine Nejad, global health lecturer with the Rice 360 ° Institute for Global Health Technologies.

- Image downloads:

-

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/04/230410_Bellytubbies_Fitlow_444-25.jpg

CAPTION: BellyTubbies team members (from left) Ana Saucedo, Anna Tutuianu, Ajay Kumar, Summer Shabanna and Pavithr Goli. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/04/230410_Bellytubbies_Fitlow_444-2.jpg

CAPTION: Ana Saucedo (left) and Summer Shabanna in the lab. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/04/230410_Bellytubbies_Fitlow_444-12.jpg

CAPTION: Anna Tutuianu, Ajay Kumar and Summer Shabanna make an adjustment. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2023/04/230410_Bellytubbies_Fitlow_444-17.jpg

CAPTION: Pavithr Goli works on the suction device. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University) - About Rice:

-

Accordion content 2.Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,552 undergraduates and 3,998 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.