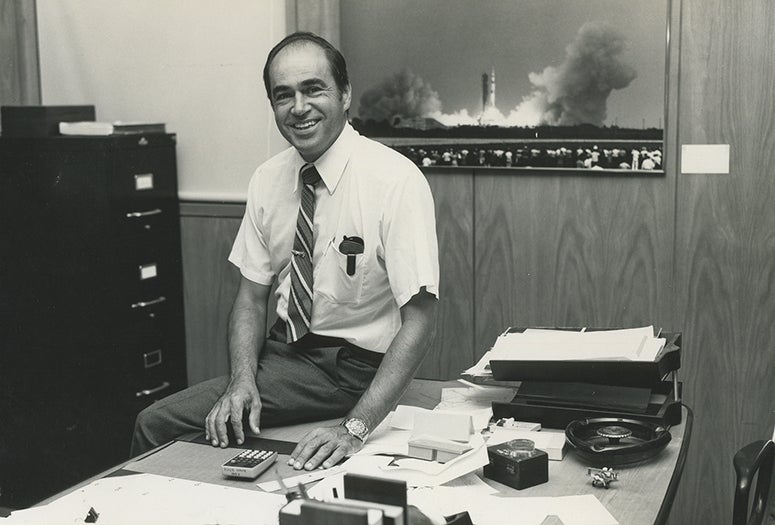

Pioneering space scientist Alexander Dessler, who taught at Rice University for 30 years after founding the first university department dedicated to the study of space science at the height of the U.S.-Soviet space race, died April 9 at age 94 in Bryan, Texas.

Dessler made lasting contributions to the study of the magnetic fields of the sun, Earth and other planets, and to the study of the “solar wind” of charged particles that stream from the sun and dominate a region of space far beyond the orbit of Pluto. He introduced the concept of this sun-dominated region of space and coined its name, “heliosphere.”

Colleagues and former students who knew Dessler at Rice say his scientific prowess was matched by his wit, generosity and care for others.

“Three key words: leader, mentor and friend,” said Tom Hill ’67, professor emeritus and research professor of physics and astronomy, who nominated Dessler for the Arctowski Medal in 2015 and penned a detailed obituary covering Dessler’s achievements. “He is widely recognized as a founding father of space physics, at Rice, in the United States and worldwide."

Data from Voyager 1, which crossed the outer boundary of the heliosphere in 2012 to become the first interstellar spacecraft, confirmed many predictions Dessler had made decades earlier about the heliosphere. The National Academy of Sciences awarded him the Arctowski Medal in honor of those contributions and others.

“I loved spending time with him,” said Melissa Kean ’96, Rice's former centennial historian. “He was, No. 1, scrupulously honest. He was funny as hell. Tongue in cheek a lot of times, but also extremely humane. He was gracious. He was engaging. He was fearless as a researcher and as an administrator. And he was a wonderful friend.”

Dessler earned his bachelor’s degree from the California Institute of Technology in 1952 and a doctorate in physics from Duke University in 1956. He had eight years experience working as a space scientist at Lockheed in Palo Alto, California, when he joined Rice. His humor and honesty are each on display in an autobiographical account of the department’s founding that Dessler published in May 2022 in the American Geophysical Union journal Perspectives of Earth and Space Scientists.

The paper’s abstract begins: “Why a Space Science Department at Rice? A one-sentence answer: Because President Kennedy came to Rice University to give a speech about the U.S. going to the moon, and Rice's president decided that Rice should show a response.”

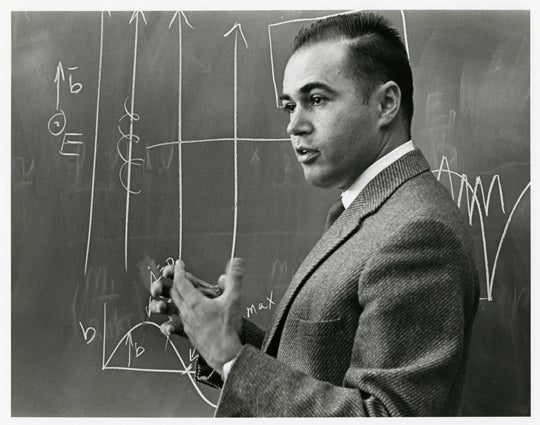

Dessler described how Kenneth Pitzer, then president of Rice, hired him quickly with little fanfare and gave him free rein to establish the department.

“By May 1963 I was in Houston full time, a 34-year-old full professor with no academic experience (except as a student), and chairman of a nonexistent Department of Space Science at Rice University,” Dessler wrote. “I remember being pleased, confident and eager. I do not recall any doubt or worry.”

To fully appreciate the challenge Dessler faced, Kean said, “You have to kind of try to put yourself back where Rice was in the early ’60s. It was much smaller. It was much less sophisticated, much less cosmopolitan.”

She said Pitzer had the vision and fundraising skills to elevate Rice to national prominence, but the path to that goal was uncharted.

“We've got all these ambitions,” Kean said. “We're going to get all this money. And then, we get NASA building the Manned Space Center in Houston. It was, ‘Go. Go. Go.’ That's where Dr. Dessler comes in. And with him come all these new faculty from California. They are not ‘Old Houston.’ They're young. They're energetic. They're vibrant. It hit this campus like a bombshell, and Dessler was the ringleader, the pied piper if you will. He was right in the middle of it all.”

Hill said the space science research program Dessler founded would go on to produce some 250 Ph.D. scientists. Hill was one, as were Rice faculty members Paul Cloutier ’67, Arthur Few ’69 and Patricia Reiff ’74. The program also produced national leaders, including David Cummings, the department’s first Ph.D., who went on to serve as executive director of the Universities Space Research Association.

Former students posted a steady stream of condolences and remembrances this week to the Rice Space Science alumni’s shared email list.

“Alex Dessler was probably the smartest man I ever met,” wrote Larry Kavanagh ’67. “The first and most important thing he taught me was that I was not here to only learn about the magnetosphere, I was here to learn how to think. The second thing was that it was more important to visualize the physics than to visualize the equations. I thought his ways were unorthodox, but it was amazing how fast he could solve problems and how correct he could be.”

Dessler would chair the Space Science department until 1969 and again from 1979-1982 and 1987-1992. The department evolved and merged with the Physics Department in the mi-2000s to form the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Aside from taking a leave of absence from 1982-1986 to serve as director of the Space Science Laboratory at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, Dessler remained at Rice until his retirement in 1993. He would go on to serve as a research scientist at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory for 14 years before joining Texas A&M University in 2007 as an adjunct professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science, where his son, Andrew Dessler, is a professor.

Following his father’s death, Andrew Dessler posted a Twitter thread that includes several video clips from an oral history he created with his father in the mid-2000s.