(Video by Brandon Martin)

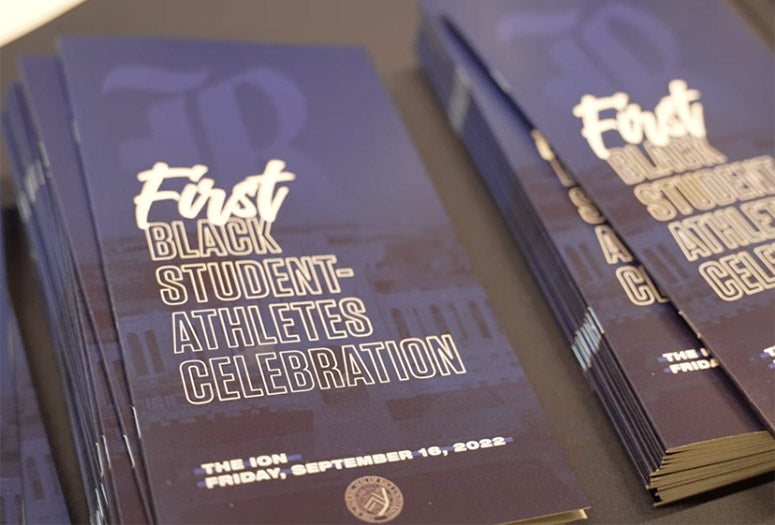

To mark the 50th anniversary of a pair of momentous occasions in Rice history, six trailblazing Owls were honored at the First Black Student-Athletes Celebration Sept. 16 at the Ion.

The event recognized four members of Rice’s matriculating Class of 1972 — football players Rodrigo Barnes '73, Stahlé Vincent '72 and the late Mike Tyler '72, and the late basketball player LeRoy Marion '72, who were the first Black men to play for the Owls — as well as volleyball and basketball player Denise Bostick '80 and track and field athlete Leila Freeman '79, the first Black women to perform for Rice following the implementation of Title IX in 1972.

The evening’s speakers highlighted the athletic achievements of the six, but it was their courage and strength outside of sport during an era of immense racial and social injustice that commanded the spotlight.

“We are here today to celebrate a group of young people whose intelligence and fortitude and talents, in addition to everything else they were, were also understood as solutions, as the solutions to long-standing national errors of racial and gender discrimination,” said Alex Byrd, Rice’s vice provost for diversity, equity and inclusion, who was part of the event’s organizing committee. “But we also want to recognize that there must have also been no small cost and sacrifice related to their coming to Rice when they did.”

Barnes, Tyler and Vincent were each three-time letterwinners on the gridiron and earned at least one All-Southwest Conference honor during their careers. All three were drafted by NFL teams: Vincent by the Pittsburgh Steelers and Tyler by the Detroit Lions in 1972, and Barnes by the Dallas Cowboys in 1973. Vincent won the Bob Quin Award, which goes to Rice’s top student athlete, in 1972.

Marion earned two letters on the basketball court and won the Billy Wohn Award as team MVP in 1972 after leading the Owls in scoring during conference play as a senior.

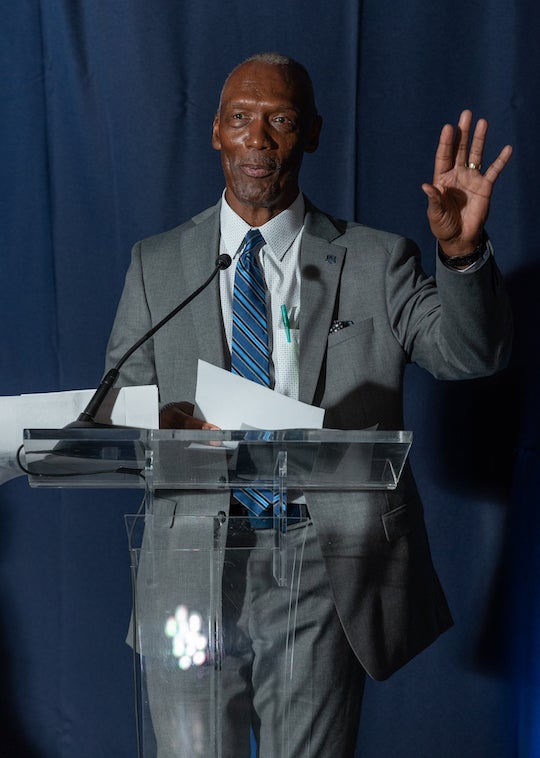

Barnes, who helped found Rice’s Black Student Union during his time on campus, spoke about the challenges he and his teammates faced after they arrived.

“1968, let's think about it. The world was a different world,” he said. “Rice University was one of many universities that were trying to put out the big lie. The big lie was centuries old, saying that Black people could not accomplish too much. … We took on that challenge, because for some reason the Bible said I was equal.”

Vincent described his arrival at Rice as “a complete culture shock for me. I went from an all-Black to an all-white environment. Hardly anybody spoke and most avoided getting close. The feeling of isolation was intense. I had two professors who did not call my name at roll call for the entire semester. When I asked if my name was on the roll, they said ‘yes, we know who you are.’

“I made the dean's list for the first grading period, a few students figured out who I was and spoke to me for about two weeks,” he said. “Over time, I realized I was hunting grades in order to be accepted instead of seeking knowledge. With this shift in focus, my mindset became more positive.”

Bostick, who earned three letters in volleyball and one in basketball from 1978-81, was unable to attend the celebration but was represented by current Rice basketball player Fatou Samb, who interviewed Bostick about her experiences on campus.

“Overall, I felt as an athlete we were held to a much higher standard,” Samb said, relaying Bostick’s message. “We represented the university on and off the court. But I was also a Black athlete, meaning I was more visible, and people paid greater attention to me and my actions. I understood I had to represent more than just me and my sport. … I promised myself and others to not give them the opportunity to look down upon me and the other Black student athletes across all sports. We all had that responsibility, and we were going to get the job done.”

Freeman was a sprinter for the Owls in 1979, running the 100- and 200-meter dashes and leading off the Owls' 4x100 relay. She emphasized that “we’ve got to do more to be loving and kind to one another” in our relationships, even if she felt comfortable personally during her time at Rice.

“I feel that I was never made to feel different,” she said. “But of course, maybe the reason for that is I was running everywhere. I ran in the morning, then I ran to class and I ran to track, I didn't walk by people, I ran by them, just ‘hi’ and ‘bye.’ I didn't know if they were looking at me weird.”

Like Byrd, Rice President Reginald DesRoches, whose daughter Shelby plays soccer for the Owls, noted the great challenges the six faced during their time on campus and the path they created for future Owls.

“Being a Black student athlete at Rice, in the early 1970s, when there were very few people that look like you, when people question whether or not you belonged at Rice, and having to deal with the stresses of performing on the court or the field while justifying that you belonged in the classroom, was really hard,” he said. “So thank you for your perseverance in what you've done. We've come a long way as a school and a society since then, but there's still much work to be done.”

Director of Athletics Joe Karlgaard also stressed the work left to be done as he thanked the evening’s honorees.

“Now, some may take it for granted that Rice has been integrated for a half-century, but our work to be a more inclusive place, not just a more diverse place, continues,” he said. “I'm grateful to our six honorees for the role they continue to play in setting a standard for Rice and compelling us to live into our mission.”

“You and your families made the brave but difficult decision to decide for you to come here and step foot on this campus, whatever the circumstances,” said Jamila Mensah ’00, president of the Association of Rice University Black Alumni and a former track athlete for the Owls. She added: “It was life-changing, not just for you, but for your families, for your families’ families, for me and my family, and for all the Black student athletes that came after you.”

The six honorees were also recognized the next day during the Rice football game, during which the current Owls wore helmets paying tribute to the 1971 team.