HOUSTON – (Oct. 20, 2022) –Creating a hydrogen economy is no small task, but Rice University engineers have discovered a method that could make oxygen evolution catalysis in acids, one of the most challenging topics in water electrolysis for producing clean hydrogen fuels, more economical and practical.

The lab of chemical and biomolecular engineer Haotian Wang at Rice’s George R. Brown School of Engineering has replaced rare and expensive iridium with ruthenium, a far more abundant precious metal, as the positive-electrode catalyst in a reactor that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen.

The lab’s successful addition of nickel to ruthenium dioxide (RuO2) resulted in a robust anode catalyst that produced hydrogen from water electrolysis for thousands of hours under ambient conditions.

“There’s huge industry interest in clean hydrogen,” Wang said. “It’s an important energy carrier and also important for chemical fabrication, but its current production contributes a significant portion of carbon emissions in the chemical manufacturing sector globally. We want to produce it in a more sustainable way, and water-splitting using clean electricity is widely recognized as the most promising option.”

Iridium costs roughly eight times more than ruthenium, he said, and it could account for 20% to 40% of the expense in commercial device manufacturing, especially in future large-scale deployments.

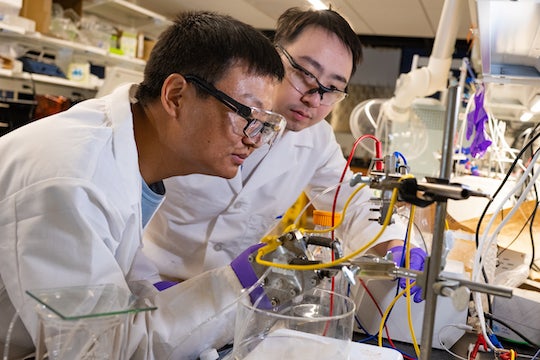

The process developed by Wang, Rice postdoctoral associate Zhen-Yu Wu and graduate student Feng-Yang Chen, and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Virginia is detailed in Nature Materials.

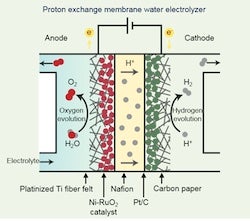

Water splitting involves the oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions by which polarized catalysts rearrange water molecules to release oxygen and hydrogen. “Hydrogen is produced by the cathode, which is a negative electrode,” Wu said. “At the same time, it has to balance the charge by oxidizing water to generate oxygen on the anode side."

“The cathode is very stable and not a big problem, but the anode is more prone to corrosion when using an acidic electrolyte,” Chen said. “Commonly used transition metals like manganese, iron, nickel and cobalt get oxidized and dissolve into the electrolyte.

“That’s why the only practical material used in commercial proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers is iridium,” he said. “It’s stable for tens of thousands of hours, but it’s very expensive.”

Setting out to find a replacement, Wang’s lab settled on ruthenium dioxide for its known activity, doping it with nickel, one of several metals tried.

The researchers demonstrated that ultrasmall and highly crystalline RuO2 nanoparticles with nickel dopants, used at the anode, facilitated water-splitting for more than 1,000 hours at a current density of 200 milliamps per square centimeter with negligible degradation.

They tested their anodes against others of pure ruthenium dioxide that catalyzed water electrolysis for a few hundred hours before beginning to decay.

The lab is working to improve its ruthenium catalyst to slot into current industrial processes. “Now that we’ve reached this stability milestone, our challenge is to increase the current density by at least five to 10 times while still maintaining this kind of stability,” Wang said. “This is very challenging, but still possible.”

He sees the need as urgent. “The annual production of iridium won’t help us to produce the amount of hydrogen we need today,” Wang said. “Even using all the iridium globally produced will simply not generate the amount of hydrogen we will need if we want it to be produced via water electrolysis.

“That means we can’t fully rely on iridium,” he said. “We have to develop new catalysts to either reduce its use or eliminate it from the process entirely.”

Boyang Li of the University of Pittsburgh is co-lead author of the paper. Co-authors are Rice graduate student Peng Zhu; graduate student Shen-Wei Yu at Virginia; physicist Zou Finfrock at Argonne National Laboratory; scientist Debora Motta Meira of Argonne and Canadian Light Source; Virginia alumnus Zhouyang Yin; and Qiang-Qiang Yan, Ming-Xi Chen, Tian-Wei Song and Hai-Wei Liang of the University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei. Co-corresponding authors are Sen Zhang, an associate professor of chemistry at Virginia, and Guofeng Wang, a professor of mechanical and materials science at Pittsburgh. Haotian Wang is the William Marsh Trustee Chair at Rice and an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

The research was supported by the Welch Foundation (C-2051-20200401), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (2020–71371), a Roy E. Campbell Faculty Development Award, the National Science Foundation (1905572, 2004808), the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing and the Advanced Photon Source of Argonne National Laboratory.

- Peer-reviewed research

-

Non-Iridium Based Electrocatalyst for Durable Acidic Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41563-022-01380-5

- Images for download

-

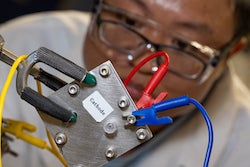

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/10/1024_CATALYST-1-web.jpg

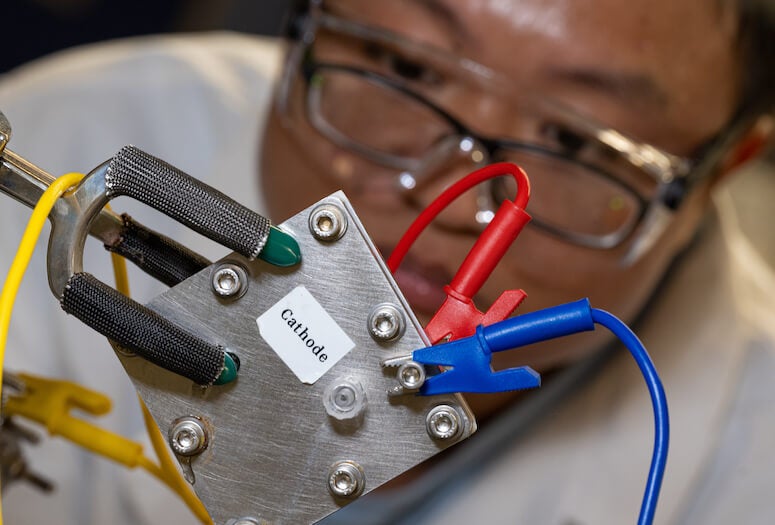

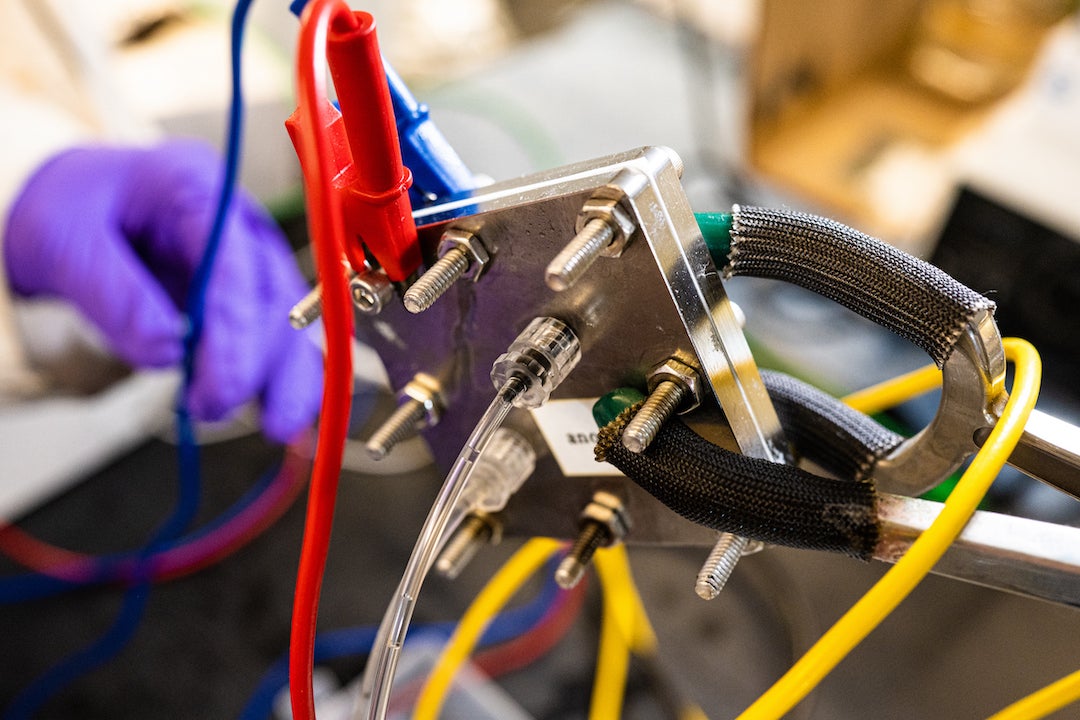

An experimental reactor at Rice University employs a ruthenium-based anode to split water into hydrogen and oxygen without the need for expensive iridium. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/10/1024_CATALYST-2-web.jpg

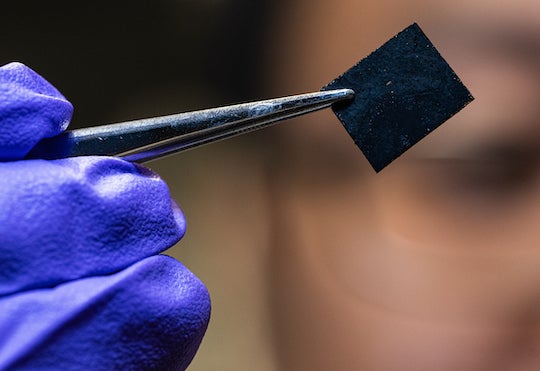

Ruthenium doped with nickel proved to be a robust catalyst to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. The anode developed at Rice University is intended to replace expensive iridium in industrial catalysts. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/10/1024_CATALYST-3-web.jpg

Rice University postdoctoral associate Zhen-Yu Wu sets up an experimental reactor that incorporates a ruthenium-based anode to split water into hydrogen and oxygen without the need for expensive iridium. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

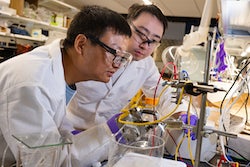

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/10/1024_CATALYST-4-web.jpg

Rice University postdoctoral associate Zhen-Yu Wu, left, and graduate student Feng-Yang Chen are co-lead authors of a study that introduced nickel-doped ruthenium as a candidate to replace expensive iridium in anode catalysts that split water into hydrogen and oxygen. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/10/1024_CATALYST-5-web.jpg

A schematic shows the experimental water electrolyzer developed at Rice University to use a nickel-doped ruthenium catalyst. (Credit: Zhen-Yu Wu/Rice University)

- Related materials

-

The Wang Group: https://wang.rice.edu

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering: https://chbe.rice.edu

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu

- About Rice

-

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,240 undergraduates and 3,972 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.