HOUSTON – (Aug. 25, 2022) – Research published this week in Science offers the clearest picture yet of the reverberating consequences of land mammal declines on food webs over the past 130,000 years.

It’s not a pretty picture.

“While about 6% of land mammals have gone extinct in that time, we estimate that more than 50% of mammal food web links have disappeared,” said ecologist Evan Fricke, lead author of the study. “And the mammals most likely to decline, both in the past and now, are key for mammal food web complexity.”

A food web contains all of the links between predators and their prey in a geographic area. Complex food webs are important for regulating populations in ways that allow more species to coexist, supporting ecosystem biodiversity and stability. But animal declines can degrade this complexity, undermining ecosystem resilience.

Although declines of mammals are a well-documented feature of the biodiversity crisis — with many mammals now extinct or persisting in a small portion of their historic geographic ranges — it hasn’t been clear how much those losses have degraded the world’s food webs.

To understand what has been lost from food webs linking land mammals, Fricke led a team of scientists from the United States, Denmark, the United Kingdom and Spain in using the latest techniques from machine learning to determine “who ate who” from 130,000 years ago to today. Fricke conducted the research during a faculty fellowship at Rice University and is currently a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Using data on modern-day observations of predator-prey interactions, Fricke and colleagues trained their machine learning algorithm to recognize how the traits of species influenced the likelihood that one species would prey on another. Once trained, the model could predict predator-prey interactions among pairs of species that haven’t been directly observed.

“This approach can tell us who eats whom today with 90% accuracy,” said Rice ecologist Lydia Beaudrot , the study’s senior author. “That is better than previous approaches have been able to do, and it enabled us to model predator-prey interactions for extinct species.”

The research offers an unprecedented global view into the food web that linked ice age mammals, Fricke said, as well as what food webs would look like today if saber-toothed cats, giant ground sloths, marsupial lions and wooly rhinos still roamed alongside surviving mammals.

“Although fossils can tell us where and when certain species lived, this modeling gives us a richer picture of how those species interacted with each other,” Beaudrot said.

By charting change in food webs over time, the analysis revealed that food webs worldwide are collapsing because of animal declines.

“The modeling showed that land mammal food webs have degraded much more than would be expected if random species had gone extinct,” Fricke said. “Rather than resilience under extinction pressure, these results show a slow-motion food web collapse caused by selective loss of species with central food web roles.”

The study also showed all is not lost. While extinctions caused about half of the reported food web declines, the rest stemmed from contractions in the geographic ranges of existing species.

“Restoring those species to their historic ranges holds great potential to reverse these declines,” Fricke said.

He said efforts to recover native predator or prey species, such as the reintroduction of lynx in Colorado, European bison in Romania and fishers in Washington state, are important for restoring food web complexity.

“When an animal disappears from an ecosystem, its loss reverberates across the web of connections that link all species in that ecosystem,” Fricke said. “Our work presents new tools for measuring what’s been lost, what more we stand to lose if endangered species go extinct and the ecological complexity we can restore through species recovery.”

Study co-authors includeChia Hsieh and Daniel Gorczynski of Rice, Owen Middleton of the University of Sussex, Caroline Cappello of the University of Washington, Oscar Sanisidro of the University of Alcalá, John Rowan of the University at Albany and Jens-Christian Svenning of Aarhus University.

The research was funded by Rice University, the Villum Foundation (16549) and the Independent Research Fund Denmark (0135-00225B).

- Peer-reviewed paper

-

“Collapse of terrestrial mammal food webs since the Late Pleistocene” | Science | DOI: 10.1126/science.abn4012

Evan C. Fricke, Chia Hsieh, Owen Middleton, Daniel Gorczynski, Caroline D. Cappello, Oscar Sanisidro, John Rowan, Jens-Christian Svenning and Lydia Beaudrot

- Image downloads

-

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/08/0825_FOODWEB-cheetah-lg.jpg

CAPTION: A predator-prey interaction between cheetahs and an impala in Kruger National Park, South Africa in June 2015. (Photo by Evan Fricke)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/08/0825_FOODWEB-aniH-lg.jpg

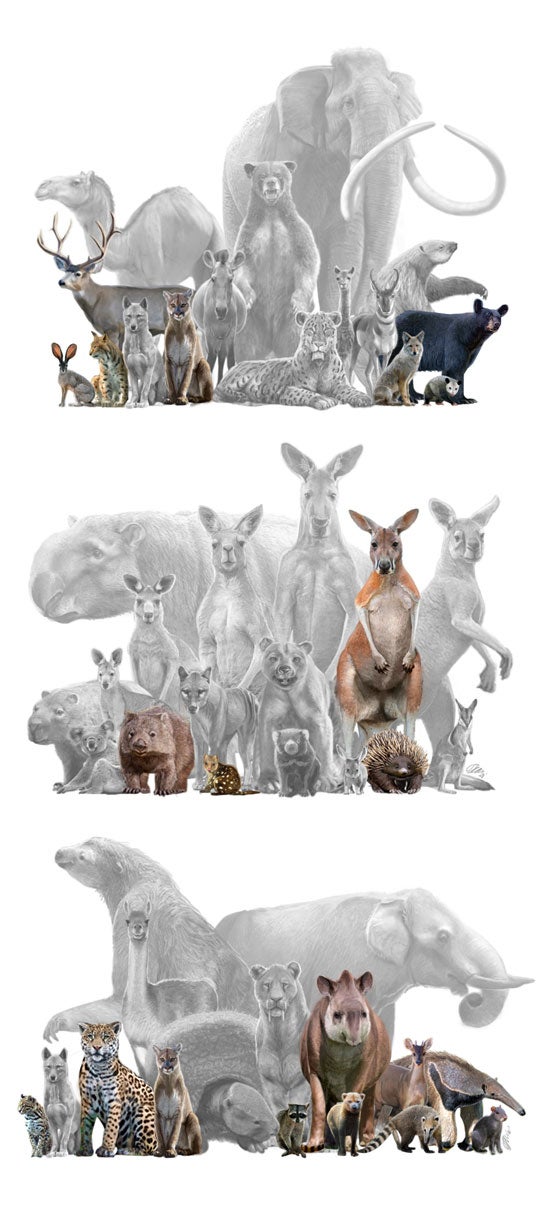

CAPTION: Illustration depicting all mammal species that would inhabit central Colombia (left), Southern California (middle) and New South Wales, Australia, (right) today if not for human-linked range reductions and extinctions from the Late Pleistocene to present. (Illustrations courtesy of Oscar Sanisidro/University of Alcalá)https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2022/08/0825_FOODWEB-aniV-lg.jpg

CAPTION: Illustration depicting all mammal species that would inhabit Southern California (top), New South Wales, Australia, (middle) and central Colombia (bottom) today if not for human-linked range reductions and extinctions from the Late Pleistocene to present. (Illustrations courtesy of Oscar Sanisidro/University of Alcalá) - Related stories

-

Lost birds and mammals spell doom for some plants - Jan. 13, 2022

news.rice.edu/news/2022/lost-birds-and-mammals-spell-doom-some-plantsCamera traps reveal newly discovered biodiversity relationship - March 3, 2021

news.rice.edu/news/2021/camera-traps-reveal-newly-discovered-biodiversity-relationshipNational parks preserve more than species – Sept. 9, 2020

news.rice.edu/news/2020/national-parks-preserve-more-speciesWhere lions operate, grazers congregate … provided food is great – Aug. 17, 2020

news.rice.edu/news/2020/where-lions-operate-grazers-congregate-provided-food-great - About Rice

-

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,240 undergraduates and 3,972 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.