English poet, painter and printmaker William Blake was largely unrecognized during his lifetime, and the original relief-etched plates he created to produce his illuminated poems were lost not long after Blake died in 1827. Today, of course, Blake is widely known as a seminal figure in Romantic-era poetry and visual art, and his surviving prints are highly sought by collectors and scholars.

Fondren Library and the Woodson Research Center have updated their collection of William Blake replica prints and plates created by renowned Blake scholar Michael Phillips. His highly authentic replicas of Blake’s illuminated poems are the culmination of more than 25 years spent researching Blake’s printing process. They offer students and researchers a rare opportunity to interact with Blake’s printing technology and understand the artistry of his original works.

“Michael Phillips is one of the big figures in Blake studies, especially when it comes to the kind of materials that Blake uses: the colors, the exact prints,” said Professor of English Alexander Regier, who teaches Blake’s work in his own courses. Regier first came across Phillips’ work while in Britain and helped the library acquire the important collection.

Phillips applies detailed historical accuracy to his work, relief-etching copper plates based on exact-size photo negatives of rare original monochrome impressions. He creates ink for the prints using period materials Blake would have used such as linseed oil and an array of dry pigments from bone black to Prussian blue. He inks the plates — a process that can take up to two hours per plate — with a leather-covered dauber and uses old hand-made paper that compares with the textured, woven papers Blake employed.

As with Blake’s originals, no two impressions are the same; each is unique. It’s work that drew the attention of the British Library, which made a short film about his process, and won Phillips international acclaim. Phillips’ research and experiments are part of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress, while Rice now boasts Phillips’ entire set of limited edition Blake replicas.

Fondren acquired “Songs of Innocence and of Experience” in 2016 and has added “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” and selections from “America: A Prophecy” and “Europe: A Prophecy,” Phillips’ latest works in this series. These sets include sample etched copper plates and other artifacts from the printmaking process, including one plate signed by Phillips himself.

“Apart from being stunning works of art in themselves — the impressions are three-dimensional with an incredible level of detail and faithfulness to Blake’s work — the prints allow students to gain a visceral insight into Blake’s working practices and the printing technology of his time,” said Joe Goetz, information literacy librarian at Fondren.

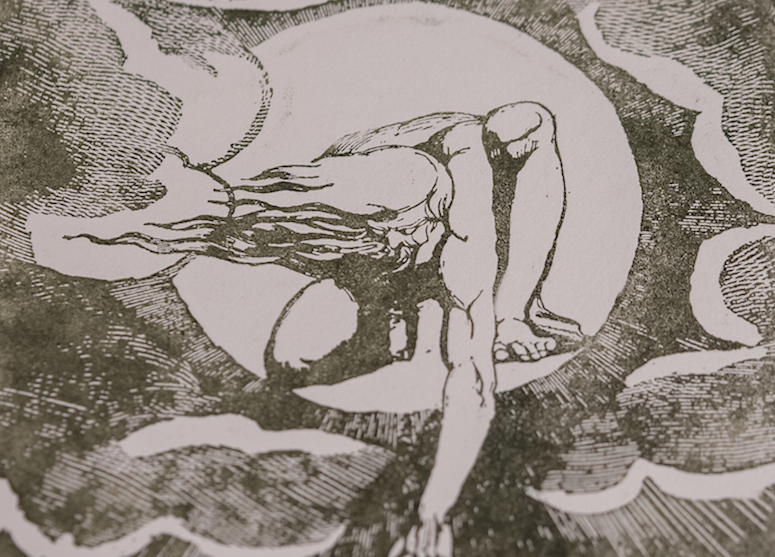

Many of Blake’s poems are now so popular they’ve been decontextualized from their original medium: a printed piece of art, the images as carefully chosen and considered as the words. We read lines like “Tyger Tyger, burning bright, / In the forests of the night;” from modern-day, image-free paperbacks without realizing that Blake’s poems were first presented to the world in a radically different fashion.

Seeing the small, richly colored and densely detailed prints for the first time is to totally reconsider Blake’s work. Even touching the materials themselves provides a sensory feast that Blake himself would no doubt appreciate.

“The reaction from students when they first see these types of materials is always one of wonderment,” said Rebecca Russell, an archivist and special collections librarian at the Woodson. “They hold the paper and see how thick it is; you can almost feel the cotton rags that went into creating this paper, in the highly laborious process that William Blake was undertaking and which Michael Phillips has recreated.”