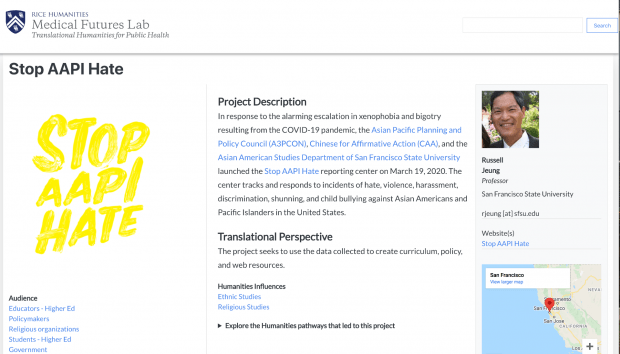

The Stop AAPI Hate self-reporting center launched last March in response to an alarming escalation in xenophobia and bigotry resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Russell Jeung, a professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University, noticed this increase in hate speech was also translating into violent attacks against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) across the U.S. — but he needed more observations than just his own to accomplish large-scale advocacy work.

“He started this website to document these incidents so that policymakers and others would be aware of the problem,” said Kirsten Ostherr, director of Rice’s Medical Humanities Program and chair of the Department of English. Soon, the Stop AAPI Hate site had received over 2,800 reports of anti-Asian incidents.

“And in late February of this year, the California Legislature enacted a law that includes funding at the level of $1.4 million, specifically to support the work of Stop AAPI Hate,” Ostherr said. “To me, that is a really good example of the kind of translational work that gets out there and has a real impact on policy and people's awareness of issues.”

Jeung launching the Stop AAPI Hate reporting center is a crucial instance of the work done in “translational humanities,” as highlighted in Ostherr’s newest project.

Translational Humanities for Public Health is an online database developed using a survey conducted last year in which Ostherr and her team of students tried to capture all of the various responses to the pandemic that involved some dimension of the humanities — whether published papers or podcasts, whether from historians, English professors, political scientists or artists.

With support from the Rice University COVID-19 Research Fund, the Humanities Research Center and the Fondren Fellows program at Fondren Library, Ostherr and her team created a website cataloging the hundreds of responses they received from across the world. Projects can be searched by researcher, location, field (37 in all), audience (is this work aimed at tech developers? Policymakers? Religious organizations?) and output (from maps to mobile apps to entire educational curricula).

The idea for such a database came to Ostherr while she was watching “often skewed and potentially harmful” data-driven visualizations reproduced on a mass scale during the early days of the pandemic in 2020.

That same spotty data was also driving the creation of new technological solutions, which rarely provide full solutions to human problems and can be actively harmful when developed with faulty data.

“Gaps in the data don't just mean missing numbers,” Ostherr said. “They mean that policy decisions may be directed by misleading understandings of what's actually going on in the world.”

The humanities, in contrast, offer myriad means of sorting through these gaps in our knowledge. And by virtue of offering a human lens through which to view the pandemic and our responses to it, they balance out technological and biomedical responses to the crisis.

Equally important is the idea of valuing human emotion as part of data science, grounding us in our shared humanity — “among the bodies from which data are derived,” as Ostherr put it.

“We intentionally use the term ‘translation,’ building on the NIH (National Institutes of Health) definition of translation as the process of turning observations in the laboratory, clinic and community into interventions that improve the health of individuals and populations,” Ostherr said. “And we did that because I and my team members really believe that the humanities offer unique and critically important insights, observations and methods that can improve the human condition and help alleviate suffering in our pandemic response.”

Ostherr and her team — an interdisciplinary group of students, staff and faculty across Rice — asked those who submitted their pandemic responses to the database to describe what made them “translational humanities” projects, in order to build methods and theories around what translational humanities work looks like.

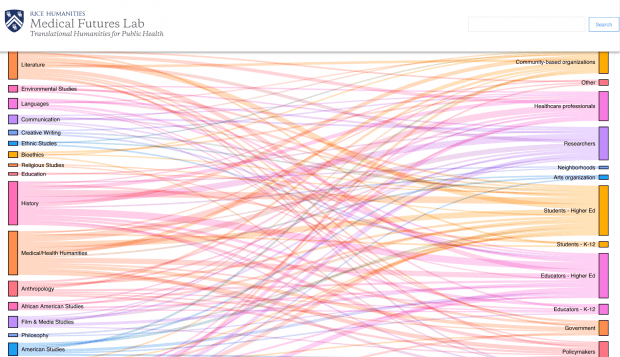

They also asked about all the different pathways that led to the project, which allowed Ostherr’s collaborator in the Computational Research Center, John Mulligan, to produce interesting data visualizations from their answers.

One heat map shows the relationships between project disciplines and researchers' training in the field. Another visualization shows the flow of humanities disciplines to their various final audiences.

Each project’s page within the Translational Humanities for Public Health database is also a wealth of information unto itself. They feature visuals, headshots, maps and links to explore, for instance, the ways in which Irish journalist and historian Ida Milne has disseminated findings from research on the 1918 flu to inform various aspects of the current COVID-19 pandemic — or perhaps to look ahead to the ways in which research from Erica Charters and her team at the University of Oxford can help answer one of the biggest questions of all right now: When exactly does a pandemic officially end?

“That was part of my motivation, really — to gather all these projects that I was seeing everywhere that I saw as really important contributions to the pandemic response, but if you weren’t looking at it from the lens of the humanities, you wouldn't see them,” Ostherr said. “It’s a different framing of what an intervention can look like.”

Find the Translational Humanities for Public Health database at transhumhealth.rice.edu.