‘Love each other,’ said legendary community activist and civil rights leader

The Rev. William Lawson didn’t need to be born in Houston to call the Bayou City his home. A figure of compassion at times when the city has needed it most, Lawson is a renowned civil rights activist and beloved community leader who’s spent his life healing the broken and brokering peace.

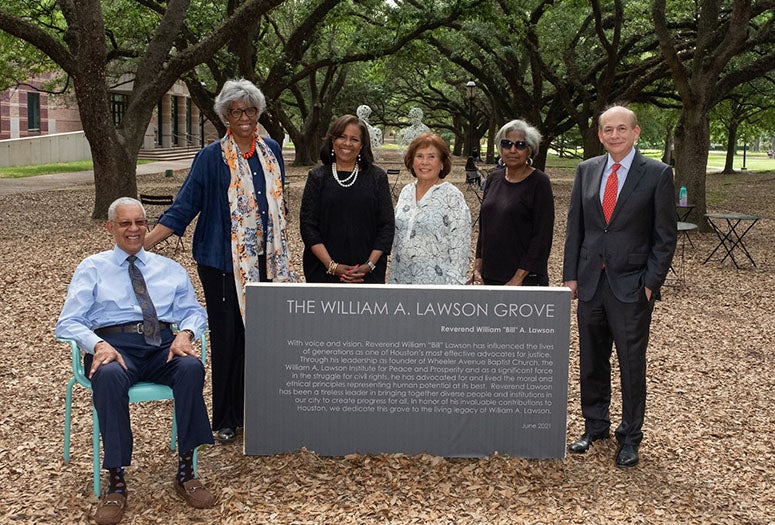

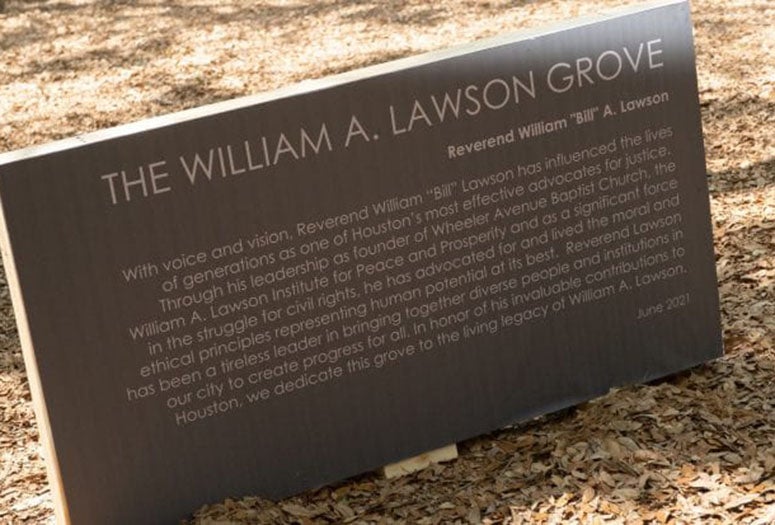

This is the legacy Rice honored in 2020 when it renamed part of the central campus quadrangle The Reverend William A. Lawson Grove, a live oak-shaded spot between Herring Hall and Brochstein Pavilion that’s a popular gathering place. The 93-year-old Lawson visited the grove with his family this week for the first time.

“People — decades from now, maybe even hundreds of years from now — will see this marker and they will remember, and I'm grateful for that,” Lawson said. “If there's anything that I'd like for my legacy to be, it is for the different cultures of humankind to get to know each other, to respect each other, and if possible to love each other.”

The Reverend William A. Lawson Grove is also home to one of Rice’s most iconic pieces of public art: Spanish artist Jaume Plensa’s “Mirror,” in which two giant genderless figures sit across from one another. Although their stainless-steel forms are composed of a profusion of interconnected letters and symbols from eight different languages, they are at peace.

“We thought in many ways that symbolized also the work of the Rev. William Lawson: his ability to bring people together of diverse backgrounds,” said Rice President David Leebron, who met with Lawson and his family as they toured the leafy area. “So in every respect, we thought this grove — located the very center of our campus, at the heart of interaction among students and faculty and staff, with artwork by Plensa — was the ideal location to honor him and his legacy.”

Lawson is the founder and pastor emeritus of Wheeler Avenue Baptist Church, which began as a 13-member congregation and one of the only churches to invite Martin Luther King, Jr. into its doors when he visited Houston. Today, the church has an estimated 20,000 members and is a vital community institution in the Third Ward.

“His legacy of advocating for justice and bringing diverse peoples together and forging a way forward — that's what we want our students to know about,” Leebron said of Lawson. “We think this will be an inspiration for many generations of Rice students.”

Woodson Research Center in Rice’s Fondren Library is home to Lawson’s papers, an archive that includes everything from decades’ worth of sermons and lecture materials to a letter of appreciation sent to Lawson by President Jimmy Carter. It’s an archive that will be useful for future students who want to know more about the man for whom the grove is named.

“I hope that generations of students will look him up and see what he did to deserve such a hallowed spot on the campus here, and we'll begin to appreciate the fact that this campus — like so many other places around the city — changed because of him,” said Lawson’s daughter, anchor Melanie Lawson of Houston’s KTRK-TV.

“But perhaps what's more important is the commitment that the university has made to demonstrate diversity by doing it in this way: he's adjacent to the chairman of the board's grotto,” she said. “And I think that students 50 or 100 or 150 years from now are gonna walk by it, and they'll put their coffee cups on it, and they'll do what they do — but they'll also notice that there's a name here, and if they look it up, then they'll learn a little bit about how important he was to our community.”

In 1960, when William Lawson was professor of bible at Texas Southern University and posting bail for students arrested at Houston’s first lunch counter sit-ins, Rice was still a segregated institution. It would remain a white-only university until a landmark court case in 1962. This history is not lost on Lawson, who was pivotal in the fight for desegregation.

“Rice decided several decades ago that it wanted to be available to people of all cultures, so right now, Rice is open to students of all backgrounds and all cultures and all economic levels,” he said. “That says a great deal about Rice. And that Rice University, which started out as a whites-only school, could dedicate a plot of land to an old Black man and feel as though he has made some contribution to Houston — that's important to me.”