Discussion in Rice’s What Is Hate? course focused this week on the March 16 murder of eight women in three Atlanta-area spas. Six of the women were of Asian descent, prompting new concerns over the surge of anti-Asian violence and sentiment across the U.S.

“Sadly, every week there is a reason to talk about the topic of the class,” said Luis Duno-Gottberg, professor of modern and classical literatures and cultures, who teaches What Is Hate? as part of the current slate of Big Questions courses from the School of Humanities. “It’s horrible that’s the case, because this is a class about hate — and there’s a lot of hate out there.”

What can art, literature, history and religion teach us about terrorism and hate crimes? Are human beings hard-wired to hate? How can we have more productive conversations about hatred and violence? These things affect our daily lives, Duno-Gottberg said; hate is not an abstract concept.

“I think our courses lately are talking about things that are urgent, because they speak to issues that we are living — that are fundamental to our existence,” he said. “These are not only ‘Big Questions’ but the questions of our time.”

To study philosophy is to learn to die

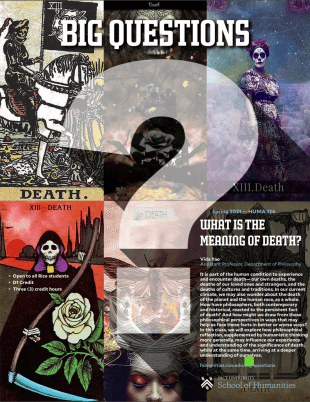

Vida Yao, an assistant professor of philosophy, is teaching What Is the Meaning of Death? this semester, during a period in which Americans have borne the loss of over 538,000 loved ones due to COVID-19. Many in the Rice community have witnessed the death of friends and family during the pandemic, Yao included.

“This last week we were doing an article about the relationship between grief and love, and it was just hard,” said Yao, who noted some students hadn’t reflected much the topic of death in depth before the course, which includes everything from Michel de Montagne readings to guest lectures by bioethicists.

“We still have so many resources against really accepting our own death that it’s like a philosophical abstraction,” she said. “Week after week the students are being asked to think about these things that otherwise can be quite difficult to think about, and they’re taking these complexities seriously.”

Contemplating keenly felt losses — the death of a parent, a best friend, a partner — provides a base of empathy and a framework for asking questions that prove vital to larger discussions about death: the course examines end-of-life care, for instance, or persistent vegetative conditions that leave a person in a complicated liminal state. Many of Yao’s students are on a pre-med track, and such considerations will one day be concrete for them as well.

But death comes for us all, not just pre-med majors. And it’s often argued, as French philosopher de Montagne famously put it, that to study philosophy is to learn to die, and thereby quell our fear of the inevitable. In that sense, Yao said she’s eager to see how her students’ views on death have shifted by the end of the course.

“To what extent can thinking about death prepare one for death? Or the death of other people?” Yao said. “It’s a good question whether it does — and what would it mean for it to really prepare someone for something like that.”

Always something to talk about

Equally inevitable in modern society is the inescapability of Disney, the scope of which requires a massive infographic to depict everything the company now owns: Hulu, ESPN, Fox, ABC, National Geographic, Hollywood Records, Lucasfilm, Marvel, cruise lines, hotels, theme parks, even a governing jurisdiction in Florida.

Charles Dove, professor in the practice of film, is teaching Who, What, Why Is Disney? this semester, focusing on the massive global influence of Walt Disney from his first cartoons to today’s empire. Dove has been screening Disney classics in the Rice Cinema — his will be the final class taught in the historic structure — and learning, he said, as much from his students as he’s teaching them.

“They've all been watching Disney+, they all know all the old Disney stuff,” Dove said. They all knew the 1928 cartoon “Steamboat Willie” featured Mickey Mouse’s earliest rival, Peg-Leg Pete, for instance. But students are less familiar with interrogating the pervasive presence of Disney or investigating the fables and contemporary events that influenced early Disney movies. That’s where Dove comes in.

“We're having fun, but we’re also talking about serious stuff like folklore and its relationship to culture,” he said. The conversations aren’t restricted to history, of course. “Disney is always in the news about something,” he said. “There’s always something to talk about.”

Keeping it relevant

With no shortage of current events to cover in his own class, Duno-Gottberg said he hopes his students will find the guest speakers in What Is Hate? helpful as they figure out how to manage and combat hatred in their daily lives and in the world at large. Starting next week, his class will be joined — virtually — by local, national and international experts on the topic.

Zahra Jamal, associate director at Rice’s Boniuk Institute for Religious Tolerance, will speak on Islamophobia in America. Cherry Steinwender, executive director of the Center for the Healing of Racism and the 2013 recipient of the Gandhi, King, Ikeda: A Legacy of Building Peace Award, will talk about the anti-racism workshops she’s led for the U.S. State Department.

Students will also hear from voices on the ground in the United Kingdom: The founder of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, Imran Ahmed, an expert on fake news and internet trolling, and the head of Anti-Hate Research for the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, Jacob Davey, a leading researcher on right-wing extremism.

The course, Duno-Gottberg noted, has already made an impact on his students, including one who recently told him it had been the main topic of conversation during her medical school entrance interview.

“Basically the whole interview was her talking to the interviewers about the class, and specifically one of the books we read, Jonathan Haidt’s ‘The Righteous Mind,’” Duno-Gottberg said. “She was fascinated, and the interviewers were fascinated with her readings in the class.

“That made me so happy,” he said. “You really want to feel that what you’re teaching is relevant to the life of your students.”