A recent study from Indiana University-Purdue University and the University of Oklahoma suggests Americans who “strongly embrace Christian nationalism” — which, the authors note, is nearly 25% of the U.S. population and growing — are also much more likely to refuse COVID-19 vaccination.

Such intersections — of religion and science, in this case — occur everywhere you look. Religion influences our daily lives in ways we might not realize. And for the last year, the pandemic has also dominated our global existence: 2.7 million people across the world are estimated to have died due to COVID-19, including 546,000 in America.

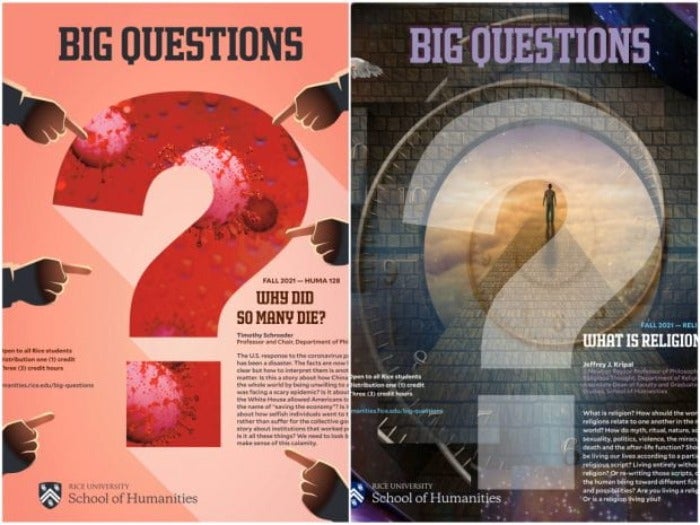

This fall, two new Big Questions courses from Rice’s School of Humanities will explore crucial issues around both topics: How can we begin to make sense of the disastrous U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Is it a story of people choosing to be selfish over suffering for the collective good or a story of institutions that failed the public at every level — or both stories and more? Should we be living our lives according to our religious convictions even if it negatively impacts others? How should religions relate to each other in the modern world?

Jeffrey Kripal, the J. Newton Rayzor Professor of Philosophy and Religious Thought and associate dean of humanities, will teach What Is Religion? — a version of a course he’s taught for 25 years that encourages students to question everything they thought they knew about themselves and their beliefs.

Timothy Schroeder, professor and chair of the Department of Philosophy, will teach a new course — titled Why Did So Many Die? The U.S. Response to COVID-19 — that offers a unique opportunity to critically examine a historical, generation-defining event as it happens.

Questions we all need to answer for ourselves

“What's exciting about teaching a course on what went wrong with the pandemic is that it will be a chance to step back and think about this enormous tragedy that we have all just lived through,” Schroeder said of his fall Big Questions course.

Even as the pandemic ebbs, he said, we’ll reckon with the effects of living in a yearlong partial lockdown, of living under conditions of fear and stress and uncertainty, and of seeing a side to our humanity that was uglier than we imagined.

“We'll need to confront what happened and ask, ‘Why? Could things have gone better? Are we to blame for our own suffering? How are we supposed to understand it all? And how should we go on after such a tragedy?’ We can't spend every day in mourning and we shouldn't just pretend it never happened. So then what? Is there a remedy? Can there be justice? Is there hope?” Schroeder said.

“These are questions I need to answer for myself, and that many students need to answer for themselves too,” he said. “This class won't tell anyone what to think, but it will give students the tools and the opportunity to figure out for themselves how they should react to the disaster America just endured.”

Changing the way we think — about everything

Kripal’s course is similarly exploratory. It wants students to question their core beliefs, including their secular and scientific ones — because within that uncertainty, Kripal said, lies the kind of wisdom that can only be earned through humility and openness. And he wants students to realize that questions central to religion can also be found throughout the science, technology, engineering and math fields, which are also, after all, expressions and knowledge of human beings

.

The course will spend a great deal of time on scientific questions and ecological concerns, he said, especially the nature of the universe and our relationship to the planet as human beings. In its more sophisticated and philosophical forms, religion has long concerned itself with questions about the deepest nature of such basic constructs as space, time and consciousness, and many modern scientists surprisingly come back to these potential answers in their own forms of mathematical and scientific knowledge. So Kripal’s class will debate these as well.

The originality of Big Questions courses like this, he said, lies in the way students’ worldviews are engaged — be they secular, scientific or religious — and challenged in a way that encourages personal growth. This has inestimable value in itself and is something students can carry with them into the world beyond Rice.

“It asks them to become more aware of and reflexive about these beliefs, to think about them in relation to other competing worldviews, and finally to refigure them after the course is over and the comparisons are complete,” Kripal said. “In short, the course is ‘existential’ in the sense it asks the students to engage the materials in a way that might well change how they think, believe and feel about, well, about everything — including themselves.”

For more on the Fall 2021 Big Questions courses, visit humanities.rice.edu/big-questions.