HOUSTON – (Dec. 2, 2021) – The Styrofoam container that holds your takeout cheeseburger may contribute to the population’s growing resistance to antibiotics.

According to scientists at Rice University’s George R. Brown School of Engineering, discarded polystyrene broken down into microplastics provides a cozy home not only for microbes and chemical contaminants but also for the free-floating genetic materials that deliver to bacteria the gift of resistance.

A study in the Journal of Hazardous Materials describes how the ultraviolet aging of microplastics in the environment make them apt platforms for antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs). These genes are armored by bacterial chromosomes, phages and plasmids, all biological vectors that can spread antibiotic resistance to people, lowering their ability to fight infections.

The study led by Rice civil and environmental engineer Pedro Alvarez in collaboration with researchers in China and at the University of Houston also showed chemicals leaching from the plastic as it ages increase the susceptibility of vectors to horizontal gene transfer, through which resistance spreads.

“We were surprised to discover that microplastic aging enhances horizontal ARG,” said Alvarez, the George R. Brown Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and director of the Rice-based Nanotechnology Enabled Water Treatment Center. “Enhanced dissemination of antibiotic resistance is an overlooked potential impact of microplastics pollution.”

The researchers found that microplastics (100 nanometers to five micrometers in diameter) aged by the ultraviolet part of sunlight have high surface areas that trap microbes. As the plastics degrade, they also leach depolymerization chemicals that breach the microbes’ membranes, giving ARGs an opportunity to invade.

They noted that microplastic surfaces may serve as aggregation sites for susceptible bacteria, accelerating gene transfer by bringing the bacteria into contact with each other and with released chemicals. That synergy could enrich environmental conditions favorable to antibiotic resistance even in the absence of antibiotics, according to the study.

Co-authors of the paper are Rice graduate student Ruonan Sun; former Rice postdoctoral researcher Pingfeng Yu, now a faculty member at Zhejiang University; associate professor Qingbin Yuan, Yuan Cheng and lecturer Wenbin Wu of Nanjing Tech University, and Jiming Bao, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Houston.

The Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20201367), National Natural Science Foundation of China (42177348) and National Science Foundation funding of NEWT (1449500) supported the research.

-30-

Read the abstract at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127895.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Alvarez Research Lab: http://alvarez.rice.edu

NEWT: https://newtcenter.org

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu

Image for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/12/1202_MICRO-1-WEB.jpg

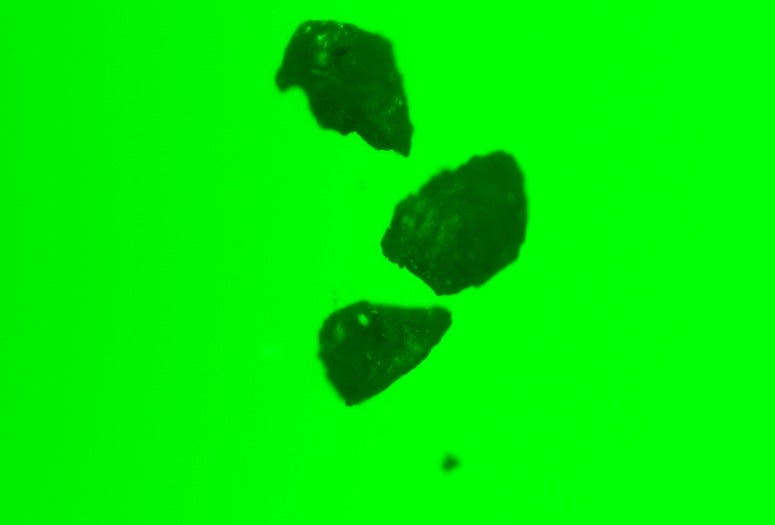

A fluorescent microscopy image shows phages adsorbed by microplastics. Rice University researchers and their colleagues found that chemical-leaching plastics draw bacteria and other vectors and make them susceptible to antibiotic resistant genes. (Credit: Alvarez Research Lab/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,052 undergraduates and 3,484 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.