Many early film theorists believed cinema could and should manipulate reality, tuning into our subconscious and encouraging the kind of exploration made possible by creating dreamlike sequences on larger-than-life silver screens. Others, such as French critic André Bazin and German writer Siegfried Kracauer, held an opposing view: that film as an art form should reflect reality as accurately as possible. Both views, however, ultimately recognize cinema as a way to understand and explain the world around us.

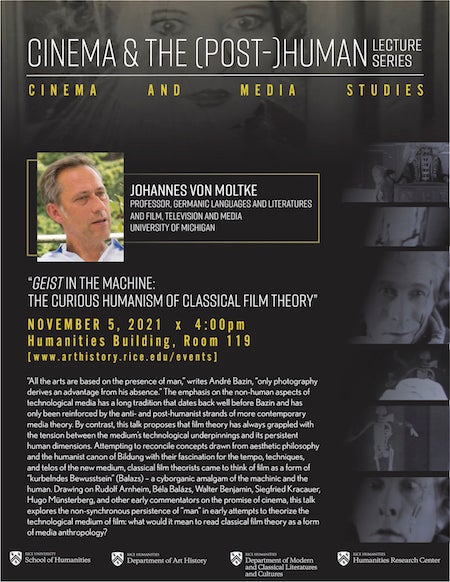

On Nov. 5 at 4 p.m., leading cinema scholar Johannes von Moltke will contrast these classical film theories with contemporary media theory in a lecture sponsored by the departments of Art History and Modern and Classical Literatures and Cultures in collaboration with the Humanities Research Center and the School of Humanities.

“Cinema has always tried to visualize the world in a way that the human eye couldn't,” said Martin Blumenthal-Barby, associate professor and co-director of Rice’s Program in Cinema and Media Studies. “Cinema always captured what was too big or too small, too fast or too slow for the naked eye.”

In a talk titled “Geist in the Machine,” Moltke will dive into “the curious humanism” of such classical film theorists as Bazin, Rudolf Arnheim, Béla Balázs, Walter Benjamin, Hugo Münsterberg and Kracauer, the latter of whom Moltke analyzed in his award-winning 2015 book “Curious Humanist: Siegfried Kracauer in America.”

The emphasis on the non-human aspects of technological media has a long tradition in film theory; take, for instance, formalist film theory that focuses intently on such things as lighting, scoring, set design, shot composition and editing. Moltke’s talk proposes that the field has always grappled with the tension between film’s technological underpinnings and its persistent human dimensions.

After all, the camera is an extension of our senses and a tool in the same way as a shovel was an advancement on the human hand. And even a movie that features no humans at all is still an act of human creation, a witnessing or ordering of things as only humans do.

“Cinema can show us the world in a way the human eye cannot,” Blumenthal-Barby said. “The larger question, then, is what can cinema and media studies contribute to the study of the Anthropocene and to the ethical imperatives arising from the planet's anthropogenic turn? And how can cinema inform our understanding of our way of worldmaking in real life?”

Cinema is not merely a form of entertainment, but actually something that can shed light on who we are and the human condition.

Hailing from a family that has impacted German and Prussian culture and history for centuries, Moltke is today equally influential in his field as a professor of film, media and television and of German at the University of Michigan. “Moltkes thread back through centuries of German history to a time when Germany hardly existed,” as Otto Friedrich put it in his 1995 book “Blood and Iron.”

Moltke is also the author of “No Place Like Home: Locations of Heimat in German Cinema,” which won the Modern Language Association’s Scaglione Prize for Best Book in German Studies, and most recently the co-editor of “Last Letters: The Prison Correspondence, 1944-45.” This collection features his grandfather and grandmother’s letters to one another while his grandfather, Helmuth von Moltke, awaited trial for his leading role in the Kreisau Circle, one of the most significant Nazi resistance groups in Germany. Helmuth von Moltke was arrested by the gestapo in January 1944 and executed by the Nazis one year later, though his wife, Freya, was able to flee Poland and ultimately ended up in America.

Moltke will be the third guest in the ongoing Cinema and the Post-Human lecture series. Previously, the series featured Vanderbilt University cinema and media arts professor Jennifer Fay and University of Toronto cinema studies professor Brian Price.

“Cinema creates illusions and fictions, and as such film has always had a propensity toward dreams and fears and anxieties and hopes,” Blumenthal-Barby said. “That's why we go to the movies — there is easy access to the subconscious desires and concerns that we are all carrying with us on a day-to-day basis.”

Because of this, Blumenthal-Barby said, film reflects our subconscious back to us in a way we wouldn’t necessarily visualize on our own.

During his Nov. 5 talk, Moltke will draw extensively on the 1927 Raymond Bernard masterpiece “Le Joueur d'échecs” (“The Chess Player”), an anti-war historical drama set in the late 18th century during the Russian domination of Polish Lithuania. Although renowned for its lush, large-scale sets that matched its ambitious scope and use of contemporary cinematic techniques such as hand-held cameras during chaotic battlefield sequences, Bernard’s film is also a haunting meditation on men made into mindless machines.

“Film has this intimate access to our ‘geist,’” said Blumenthal-Barby, referring to the German philosophical term that denotes a combination of soul, mind and spirit — the same “ghost in the machine” referred to by British philosopher Gilbert Ryle in his famous description of René Descartes' mind-body dualism.

“Cinema is not merely a form of entertainment, but actually something that can shed light on who we are and the human condition.”

For more information or to register for the Nov. 5 lecture, visit arthistory.rice.edu/events.