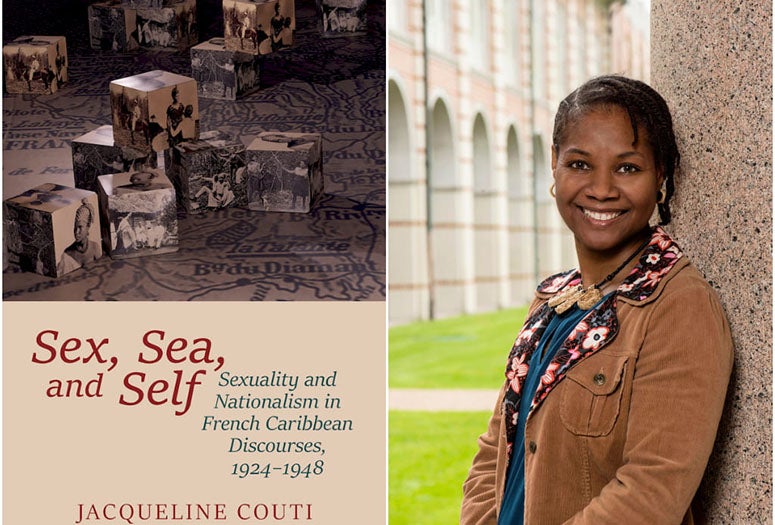

“Sex, Sea and Self,” Jacqueline Couti’s second book, continues her research examining the construction of self and identity through what she terms “dangerous Creole liaisons” — the problematic interconnections — between sexuality and nationalism within the French Caribbean and Black Atlantic.

An extensive and expansive work written in two parts — “She Says” and “He Says” — “Sex, Sea and Self” will be released in November.

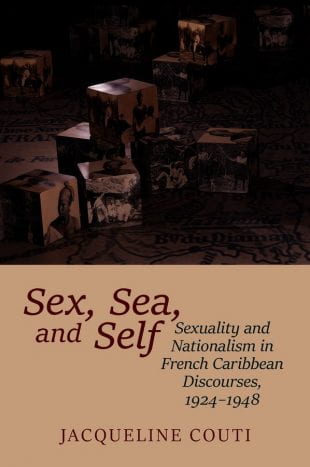

Couti, the Laurence H. Favrot Professor of French Studies in the Department of Modern and Classical Literatures and Cultures, has spent her career studying the trans-Atlantic and transnational connections between cultural productions from continental France and its former colonies such as Martinique and Guadeloupe.

“We have long sexualized the sea and the people who live next to the sea,” Couti said.

Just listen, she said, to any Serge Gainsbourg song for notably French examples. “Tu es la vague, moi l'île nue” (“You are the wave, me the naked island”) sings Gainsbourg in his most famous composition, “Je t'aime moi non plus.” Then there’s “Sea, Sex and Sun,” from which Couti derived some partial inspiration for her book’s title.

There’s even a word for this in France, born out of a French Creole word: doudouisme, the tendency to exoticize and fetishize the people and places of overseas French territories, especially those of the West Indies, all of it wrapped up in a male colonial gaze. “Doudou” has also become a term, Couti said, for the sexualized Black enchantress or seductress, who often has lighter skin.

This sexualization of bodies in the French Caribbean and Antilles is a theme that is particularly prominent in colonial and postcolonial literature written about, and by, the people in those island or coastal countries, often male writers.

“Black male authors in colonial and also postcolonial times have used the sexualization of female bodies to advance their masculine agenda,” Couti said. “So these men were writing like white authors embracing exoticism but they still used sexuality in an erotic and often exotic fashion.”

Couti, however, is interested in what both male and female Black writers from Martinique and Guadeloupe have had to say about their own notions of gender, race, identity and, of course, sexuality.

“Sex, Sea and Self” examines neglected French texts by Black writers from the first half of the 20th century in order to reassess the place of French Antilles and French Caribbean literature within current postcolonial thought and visions of the Black Atlantic. Couti’s work means the analysis of some of these texts is also now available to readers of English for the first time.

In 1948, Lucette Ceranus Combette became the first woman of color to be awarded a literary prize for publishing a book in France, under the pen name of Mayotte Capécia. “Je suis Martiniquaise” (“I Am a Martinican Woman”) has attracted the attention of scholars since its publication, and was presented by the press as a semiautobiographical novel about her life and relationship with a white Vichy naval officer who abandoned her in Martinique with their son.

The beautiful mixed-race protagonist, Mayotte Capécia, is trying to better herself while seeking to embrace French ideals of respectability. Mayotte often presents herself as shunned from white social circles and believes she is also shunned by some members of her own family and hometown as a “race traitor” due to her son’s whiteness. However, Mayotte does not seem to realize that her relationship with a man who was dedicated to the Pétain regime could be problematic amid the fall of the Vichy regime. The novel ends as Mayotte departs for Paris to find a different identity in France — ideally, for her, with another white man.

Mayotte’s is just one of the stories examined in “Sex, Sea and Self,” which digs into doudouisme, the deconstruction of the “white Creole” myth and the dangerous liaisons of Black and white bodies at a time when sexualization went hand in hand with violence.

The book’s bifurcated approach — the first section devoted to women writers, the second to men — was important to understanding the different ways men and women viewed their own sexuality and each other’s, recalibrating overly simplistic understandings of the victimization and alienation of French Caribbean people.

“Men and women do not share the same experiences,” Couti said. “So why do we give men the authority to define us?”

The work of women from various classes, socioeconomic backgrounds and skin color further diversifies the perspectives offered, looking beyond the Négritude movement to explore how notions of Blackness in the French Caribbean remain entangled with French Creole and French continental principles of whiteness.

“How do you relate to Blackness as someone with lighter skin? Or darker skin?” Couti said.

Couti laid the foundation for this work with her first book, “Dangerous Creole Liaisons: Sexuality and Nationalism in French Caribbean Discourses from 1806 to 1897.” With her new book, she examines sexuality as an instrument of political and cultural consciousness in the chaotic period between 1924 and 1948. Studying this sexual imagery demonstrates the significance of agency and the legacy of the past in cultural resistance and political awareness.

Négritude, a movement which emerged in the 1920s as a revolt against historical French colonialism and racism, is just one example of this artistic and political resistance. This self-affirmation of Black culture and heritage has its roots in Martinique and French Guiana (as well as Senegal), two colonies on the sea where memories of slavery were still vivid and recent.

Upon traveling to Paris and meeting other intellectuals, both Black and white, writers like Martinique-born Aimé Césaire found — and expressed — a Black pride and distinct identity that was in sharp contrast to French assimilationism. Black women in these spheres also found themselves pinned against the “French national misogyny” of the time, Couti said.

“As such, simply promoting one’s own culture was an act of resistance and agency in the 1940s on a small island, particularly for women,” Couti said. “Self-awareness is the first step; then everything changes.”

Couti’s goal, she said, is not to lionize these authors or put them on pedestals but rather to remind readers of these individuals’ humanity in a world bent on dehumanizing them. Her work reveals a fascination with what it means to be human in a world where others always want to define you, and not always in the best light.

“Isn’t the greater achievement simply to be human with all our weakness and glory instead of superhuman or extraordinary?” Couti said. “To be accepted as a human, like any another?”

With “Sex, Sea and Self,” Couti provides an analysis that illuminates the multifaceted and conflicted relationships between France and its overseas departments while also expanding the ideas of nationhood in the Black Atlantic. It’s an exciting new perspective and brings cutting-edge theoretical studies of Caribbean literature to a broad scholarly audience.

“Sex, Sea and Self” will be available in both hardcover and paperback formats Nov. 1 through the Oxford University Press.