Larry McMurtry ’60, who launched his writing career as a student at Rice University — a place he considered his “intellectual home”— and became famous for such memorable novels as “Lonesome Dove,” “The Last Picture Show” and “Terms of Endearment” among his dozens of other books and screenplays, has died. He was 84.

McMurtry wrote more than 30 books, two collections of essays, three memoirs and more than 30 screenplays. Best known for his Western novels, McMurtry won a Pulitzer Prize for “Lonesome Dove,” a blockbuster novel that tells the epic story of two retired Texas Rangers who encounter one adventure after another as they drive a herd of stolen cattle to Montana. He later won an Academy Award as one of the screenwriters of “Brokeback Mountain,” a critically acclaimed movie about two ranch hands who fall in love.

“He wrote about the Texas he knew from his own life, and then the Old West as he heard it through the stories he heard on his grandfather’s porch,” President Barack Obama said in 2015 when he presented McMurtry with the National Humanities Medal.

“Larry McMurtry was one of the most influential Texas novelists who updated the genre of the Western and helped preserve its relevance,” said Scott Derrick, an associate professor of English at Rice.

Born in 1936 in Wichita Falls, Texas, and raised outside Archer City, McMurtry said he began his literary journey when he 6 years old. He recalled that he was living on a cattle ranch when his cousin gave him some adventure books that transformed him into an avid reader. “Reading to me is the perfect pleasure,” he said in an interview with Rice Magazine. “It’s stable, inexpensive and gratifying. It’s everything a culture should be.”

Early in life McMurtry decided to defy his parents, who wanted him to stay at the ranch and herd cattle. Instead, he was determined to become a writer and, as he would later describe his craft, “herd words.”

McMurtry enrolled at Rice in 1954 after seeing a television program showing what was then called the Rice Institute. “The campus had what I supposed to be an Oxford-like look,” he said.

One of his fondest memories of Rice was the Fondren Library, which at the time contained 600,000 volumes. He recalled spending hours wandering around the library, an experience that inspired him to romanticize Fondren in his novel “All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers.” The book’s hero, Danny Deck, sleeps on the couches in the campus library.

At Rice, McMurtry took literature and writing courses from professors Alan McKillop, Jackson Cope, Wilfred Dowden and George Williams ’23. Although he left Rice before graduating, McMurtry said, he thought of the university as the place where he began to read seriously. “I love Rice and think of it as my intellectual home,” he said.

From Rice, McMurtry transferred to North Texas State University (now University of North Texas) in Denton, where he took creative writing classes and received his bachelor’s degree in 1958. He returned to Rice for graduate studies in English, earning a master’s in 1960, and briefly considered pursuing a doctorate before deciding a master’s was all he needed. By then, he had already finished the drafts of two novels, and he used the manuscripts to enter the Wallace Stegner Fellowship creative writing program at Stanford University.

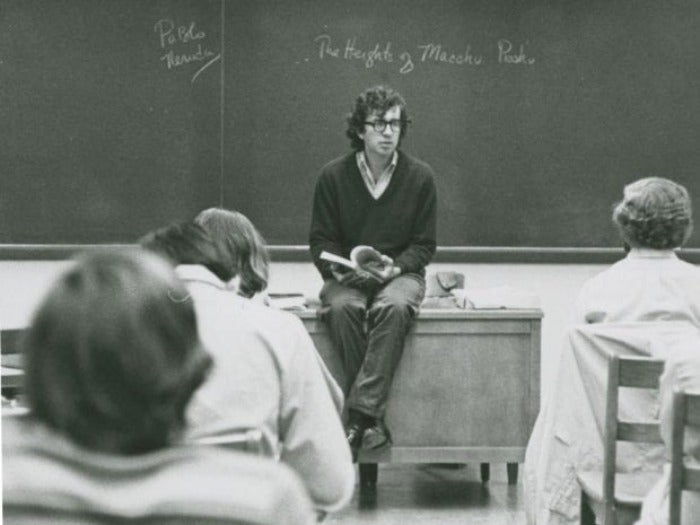

McMurtry taught at Texas Christian University before moving back to Rice to teach freshman English and creative writing.

“Many of the senior and emeritus members of the Rice English department have fond memories of their friend Larry McMurtry," said Kirsten Ostherr, chair of the Department of English. "He famously wore a sweatshirt that read 'MINOR REGIONAL NOVELIST' — a sign of his humor and humility, even as his work earned international acclaim. He inspired generations of students and faculty at Rice.”

McMurtry's time in Houston deeply influenced his work, most notably his famous "Houston trilogy," which culminated with "Terms of Endearment" in 1975.

“Rice was only one location in McMurtry’s Houston landscape: he imbibed and reflected upon Houston in his novels,” said Dean of Humanities Kathleen Canning. “Moreover, McMurtry's non-fiction book, 'In a Narrow Grave,' became what CNN presidential historian Douglas Brinkley called 'the gold standard for understanding Houston’s brash rootlessness and civic insecurities.'”

In time, McMurtry decided to leave teaching and dedicate more time to writing. He developed a disciplined routine, waking up early every day, including holidays, and writing five pages; with experience, he doubled his daily output to 10 pages. Well into the 21st century, McMurtry wrote on an old manual typewriter, never on a computer, not even to send an email or do research on the internet. For research, he said, he depended upon his reading habits. After growing up on a ranch that for many years had no books, his personal library contained close to 30,000 volumes.

“Larry McMurtry was a giant figure in U.S. Western studies, and like many celebrated writers, he had a love/hate relationship with cowboy mythology and the idea of the US West as a place where no one read,” said Krista Comer, English professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies at Rice. “His friendship with Susan Sontag and his massive love affair with books are well known. Less known are important writerly collaborations and understandings of the West such as that with the Laguna Pueblo writer Leslie Marmon Silko. If audiences knew his Lonesome Dove series best, among critics, his quirky ‘Reading Walter Benjamin at Dairy Queen’ captured both his learnedness as well as his complex pull toward the lonelier hinterlands of Texas.”

When he wasn’t writing or reading, McMurtry was selling antiquarian books. He owned what became a famous book store in Archer City, Booked Up, that housed an estimated 400,000 volumes. It became a small-town tourist attraction, drawing visitors from around the world who stopped by to buy rare books and catch a glimpse of a lion of Texas literature.

As he approached the end of his career, McMurtry said he hoped he would never write another novel because he thought authors who kept writing for too long got worse at their craft.

“Writing great fiction involves some combination of energy and imagination that cannot be energized or realized forever,” he said.

In a lecture he gave at Rice in 2009, McMurtry voiced concern that technology and the internet were replacing books and contributing to the dying culture of literature. He loved books and wanted them to live forever, long after the last chapter of his own life.

“My research has been my lifelong reading,” he once said. “Mostly the reading fertilizes the writing. Reading is the aquifer that drips, spongelike, into my fiction.”