When people enter a dark room, they’re likely to flip a light switch. Plants do something similar — but the protein switches they flip sense whether light is present.

As these phytochromes transform from quiescent to light-activated states and back, they help plants regulate their life cycles around daily and seasonal rhythms, measuring the length of day to prepare for the start of summer or the coming of winter.

A multi-institution team of researchers that includes Rice bioscientist and co-principal investigator George Phillips and co-lead author and former postdoctoral researcher Jonathan Clinger has gained a better look at the mechanism by which plants manage photosynthesis to absorb the sun’s bountiful energy.

Their paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences describes a reversible phytochrome photosensor found in a cyanobacterium, Thermosynechococcus elongatus, that shares characteristics with plant proteins. The protein is expressed in the dark but is awakened by light in a fraction of a second.

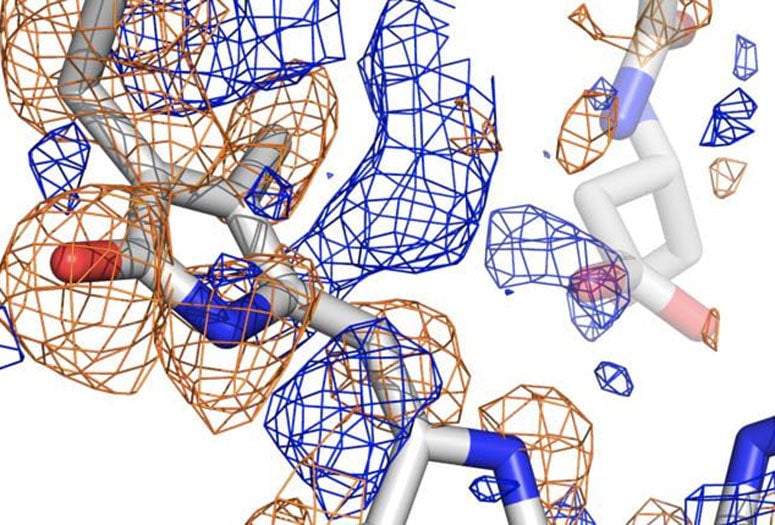

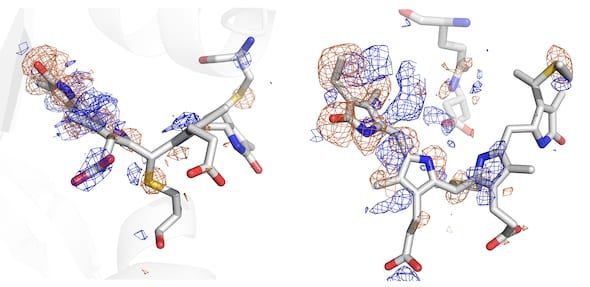

Until now, that process was impossible to see. But a powerful form of X-ray crystallography employed by Phillips and his collaborators through the National Science Foundation-supported BioXFEL Science and Technology Center allowed them to witness the sensor’s conversion in great detail.

The team used the newly upgraded X-ray free-electron laser at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University to analyze phytochromes, running streams of the protein crystallized at various states through the femtosecond (quadrillionths of a second) beam to capture information about their atomic structures. Powerful computers then analyzed the high-resolution diffraction data to build pictures of the protein in a variety of conformations.

The work follows an earlier proof-of-concept paper in Nature Methods by the team, which also includes Rice senior scientist Mitch Miller, a co-author of both.

“We are getting closer to making atomic ‘movies’ of proteins in action,” said Phillips, Rice's Ralph and Dorothy Looney Professor of Biochemistry and Cell Biology and director of education and diversity for the BioXFEL Center.

“When organisms need to change their behavior with respect to light, sensors pick up the photons and send a signal downstream to the response machinery,” he said. “This study helps define how that signal works in photosynthetic organisms, which obviously need light to thrive.”

Co-principal investigator Richard Vierstra of Washington University in St. Louis said such photoreceptors have been studied for 60 years, but only now are their processes being seen in detail. The images revealed how the chromophore of the protein, known as PixJ, rotates by changing the bonds between two pyrrole rings when activated or deactivated by blue and green light.

Primary funding for the research came from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis and the National Science Foundation.