Like finding that needle in the haystack every time, your T cells manage what seems like an improbable task: quickly finding a few invaders among the many imposters in your body to trigger its immune response.

T cells have to react fast and do so nearly perfectly to protect people from diseases. But first, they need a little “me” time.

Rice University researchers suggest that has to do with how T cells “relax” in the process of binding to ligands -- short, functional molecules -- that are either attached to the invaders or just resemble them.

The look-alikes greatly outnumber the antigen ligands attached to attacking pathogens. The theory by Rice chemist Anatoly Kolomeisky and research scientist and Rice alumnus Hamid Teimouri proposes that the T cell’s relaxation time -- how long it takes to stabilize binding with either the invader or the imposter -- is key. They suggested it helps explain the rest of the cascading sequence by which invaders prompt the immune system to act.

The inappropriate activation of a T cell toward its own molecules leads to serious allergic and autoimmune responses.

The researchers’ study appears in the Biophysical Journal.

T cells operate best within the parameters that control a “golden triangle” of sensitivity, specificity and speed. The need for speed seems obvious: Don’t let the invaders infect. And it is important because T cells spend so little time in the vicinity of the antigen-presenting cells, so they must act quickly to recognize them. Specificity is most challenging, since self-ligand imposters can outnumber invaders by a factor of 100,000.

“It is amazing how T cells are able to react so fast and so selectively. This is one of the most important secrets of living organisms,” said Kolomeisky, a professor and chairman of Rice’s Department of Chemistry and a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

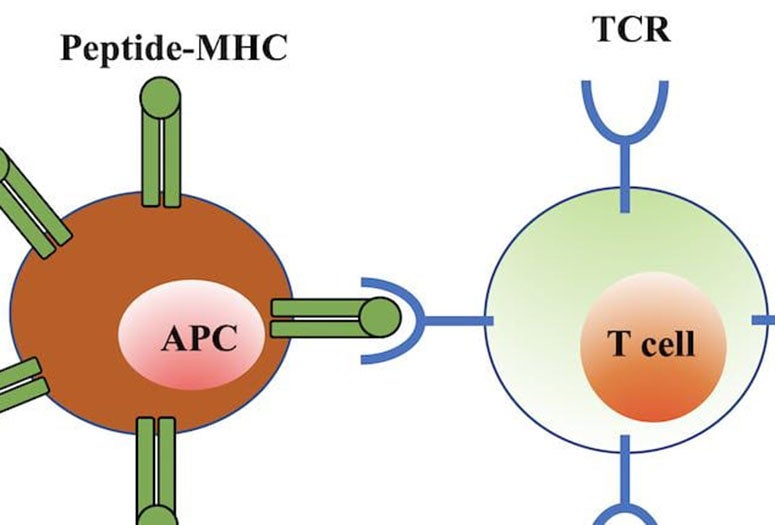

Their approach was to build a stochastic (random) model that analyzed how T cell receptors bind step-by-step to the peptide major histocompatibility complexes (pMHC) on the surface of antigen-presenting cells. At a high enough concentration, the bound complexes trigger the immune cascade.

The mathematical model aligned with experimental results that suggest T cell activation depends on kinetic proofreading, a form of biochemical error correction.

Proofreading slows down the relaxation for wrong molecules, and this allows the organism to start the correct immune response.

While the theory helps explain the T cells’ “absolute discrimination,” it does not explain downstream biochemical processes. However, the researchers said timing may have everything to do with those as well.

In a “very speculative” suggestion, the researchers noted that when the binding speed of imposters matches that of invaders, triggering both biomolecular cascades, there’s no immune response. When the more relaxed binding of pathogenic ligands lags behind, it appears more likely to reach a threshold that triggers the immune system. Kolomeisky said the concept could be validated through experimentation.

He and Teimouri wrote that many other aspects of T cell triggering need to be explored, including the roles of the cellular membranes where receptors are located, cell-cell communications, and cell topography during interactions. But having a simple quantitative model is a good start.

“Our theory can be extended to explore some important features of the T cell activation process,” Kolomeisky said.

The Welch Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics at Rice supported the research.

-30-

Read the abstract at https://www.cell.com/biophysj/fulltext/S0006-3495(20)30451-3.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Kolomeisky Research Group: http://python.rice.edu/~kolomeisky/

Rice Department of Chemistry: https://chemistry.rice.edu/

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: https://naturalsciences.rice.edu/

Image for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2020/06/0622_T-CELL-1-web.jpg

Rice University scientists’ simple model of T cell activation of the immune response shows the T cell binding, via a receptor (TCR) to an antigen-presenting cell (APC). If an invader is identified as such, the response is activated, but only if the “relaxation” time of the binding is long enough. (Credit: Hamid Teimouri/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,962 undergraduates and 3,027 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 4 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.