Jim Blackburn sees Houston as a perfect reflection of the 20th century, an emerging but disorganized city at the turn of one century that boomed into a diverse economic powerhouse by the next.

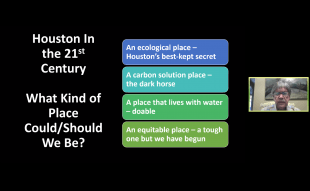

But in the 21st century, Houston “finds itself a little lost” as climate change forces the city to think about it’s very survival.

“We’re a bit like a monarch butterfly,” Blackburn said. “The chrysalis is formed, the butterfly has emerged. The 20th century was great – but are we going to make it?”

Blackburn, an environmental lawyer and professor in the practice of environmental law in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at Rice University, reviewed the city’s history and his offered thoughts on its future in an OpenRICE webinar, “This Place Called Houston,” on Aug. 28.

Speaking one day after Hurricane Laura avoided Houston and crashed ashore in Louisiana, Blackburn warned that a hurricane directly hitting the Houston Ship Channel would be a “death knell” for the city. A devastated ship channel would ravage Houston’s economic system and potentially spill “100 million gallons of oil and hazardous substances,” he said. The ecological and economic damage would be comparable to the effects of Chernobyl, he argued, a point he elaborated on in an opinion piece published in the New York Times.

“This would be the worst environmental disaster,” he said in the webinar. “It would probably be the worst economic and probably, depending on how evacuation was handled, possibly the worst loss of human life in the United States since the Galveston storm of 1900.”

As he reviewed the city’s history, Blackburn noted that oil changed everything. The Spindletop oil strike near Beaumont happened just four months after the 1900 hurricane devastated Galveston, which had been the state’s premiere city. Houston, which expedited the dredging of a ship channel to the Gulf, was poised to become the most important city in Texas.

That the Port of Houston and the Panama Canal both opened in 1914 was no accident, Blackburn said.

“The idea of making that channel opening coincide with the Panama Canal was absolutely brilliant – because Houston became the first stop for vessels either going into the Gulf of Mexico and coming to the United States from the Pacific, or the last stop before you go through the canal,” he said. “It really put Houston on the shipping map, something that oil and gas had already begun.”

Thanks to massive expansion in the chemical industry after World War II, the Texas Gulf Coast boomed with refineries and chemical plants. The Houston Ship Channel was the industry’s focal point.

The integration of lunch counters in August, 1960, steered Houston towards becoming one of the most diverse cities in the country. The Astrodome, the Offshore Technology Conference and NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center (later renamed the Johnson Space Center) helped Houston become a technology hub during the 1960’s.

By the millenium, Houston was “certainly the epitome of a 20th century success,” Blackburn said. Population saw “tremendous growth,” as did many Texas cities, with people leaving places like New York City and Chicago.

The 21st century brought massive flooding during Tropical Storm Allison in 2001, which led to revision of the city’s flood plain maps.

“They considered it an aberration at the time, although it was a precursor,” he said. “It was the first indication of the climate change rainfall that we have been inundated with in the first 20 years of the 21st century.”

Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and even Ike were near misses, Blackburn said, but the Tax Day and Memorial Day floods of 2016, Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and last year’s Tropical Depression Imelda were further evidence of how climate change was impacting Houston.

“We’re seeing the outer limits of the bell curve of distribution being redefined by the rarer incidents, the incidents (like Allison) that are off the charts,” Blackburn said. “This summer is being identified as being ‘off the charts.’ We keep having rainfall events, we keep having temperature events. The Gulf of Mexico heat being off the (charts) – that’s climate change.”

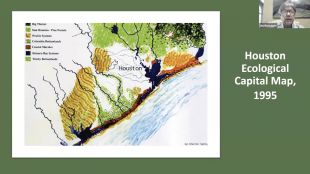

Blackburn believes Houston’s ecological capital is a treasure that’s the city’s best kept secret. The Columbia Bottomlands are a “wonderful bunch of old growth trees” near the Brazos River. Several species of trees there have “tremendous” potential for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it. According to his research, a live oak can remove upwards of five tons of carbon dioxide in 30 years. After 50 years, it goes up to 10 tons per tree.

“That becomes very important in a long-term carbon dioxide reduction strategy. That will be the centerpiece of every corporation in the 21st century.”

The Coastal Wetlands are “fabulous from a fish production standpoint,” he said. The wetlands are nurseries for fish and shellfish, for example, housing about six thousand shrimp, brine and white per acre, as well as blue crab and juvenile flounder. These marshes also remove and store carbon dioxide via photosynthesis.

Houston sits on a prairie that covers much of the region’s crop land, but some of that prairie survives as parks and conservatories. The native plants here are “carbon pumps,” Blackburn said. “And carbon dioxide storage in the soil is both real and can become a commodity” with the potential to be the largest “carbon sink” in the U.S.

Blackburn said companies have to understand their carbon footprints and work to reduce them in the near future with carbon capture and storage.

The energy industry thinks “in terms of pumps and valves, then patents and technologies,” he said. “But here’s the mindblower. Photosynthesis may be the technology that will save the oil and gas industry. And we have a fabulous amount of that resource right around Houston.”

Houston’s land resource is disorganized, Blackburn argued. As a Baker Institute Rice Faculty Scholar and co-director of the university’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters Center (SSPEED), he’s working on the Baker Institute Soil Carbon Storage Standard. It will create a set of standards and a certification entity for carbon credits, “so buyers can buy with confidence in U.S., ecologically sound carbon storage,” he said.

Blackburn will lead a six-week course this fall through the Glasscock School of Continuing Studies, The United States’ Green Future: Economy + Environment. The class will dicuss carbon-neutral-design and carbon-neutral-thinking and the circular economy.

He also writes ecology-inspired poems every day during the pandemic and pairs it with art by Houston native Isabelle Chapman. They can be seen on his blog, Virus Vigil.