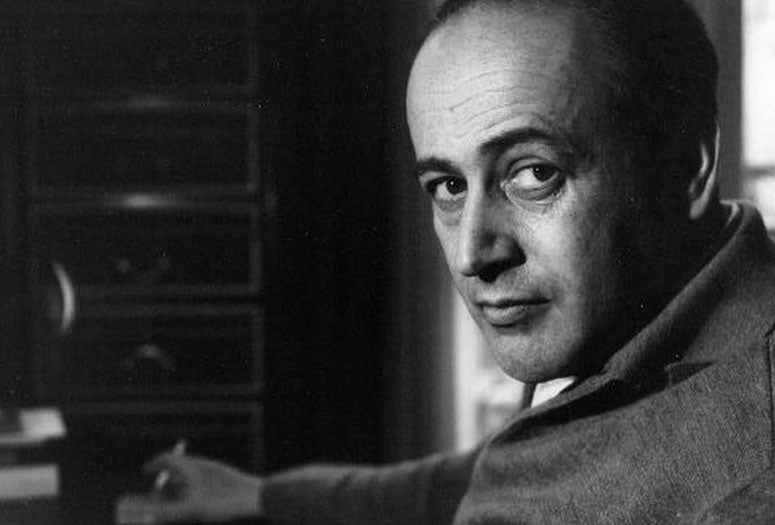

As one of the most important and influential poets of the 20th century, Paul Celan’s life and work reflect a central ethical and literary concern of his own time: “Can one still write poetry after Auschwitz?”

This question — originally posed by the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno — highlights the ethical urgency of Celan’s work. Adorno posited that writing poetry after the Holocaust could only be “barbaric,” but it was Celan who found a new and highly personal lyrical language that allowed him to respond to the continued possibility of poetry.

An upcoming conference at Rice, “Life Lines: Paul Celan’s Poetic Recreation of the World,” will examine the way in which his poetry is embedded in both historical experience and his own life. The conference takes place March 6-7 in the Moody Center for the Arts and is presented by Rice’s Department of Classical and European Studies.

Speakers from across the United States and Europe will present research on Celan’s life and the future of Celan scholarship, including University of Tübingen professor Barbara Wiedemann, Harvard University professor Judith Ryan and well-known Celan translator Pierre Joris, a poet in his own right.

Rice professor of German studies Klaus Weissenberger will also be among the esteemed lineup of presenters. During his more than four decades at Rice, Weissenberger has become one of the world’s leading experts on Celan, having written three books and countless articles about the poet.

“These books kind of set the standard for subsequent scholarship on both sides of the Atlantic,” said Christian Emden, professor of German studies and chair of the Department of Classical and European Studies.

And with Weissenberger's retirement looming in 2021, he and his colleagues in the department thought a conference on Celan would be a fitting conclusion to a long and extremely productive scholarly career.

Born to a Jewish family in Romania, Celan barely survived deportation, life in a Nazi ghetto and forced labor in a Transnistria internment camp. His parents didn't survive the camp: Celan's father died of typhus, and his mother was shot after being exhausted by forced labor.

Fluent in Romanian, French and German, Celan lived in exile in Vienna and Paris following World War II, but chose German — the language of his perpetrators — for his poetry, famously composing what is perhaps one of the most haunting and complex poems in the German language, “Todesfuge” (Death Fugue).

Written around 1945 but not published until 1948, the poem gives stark lyrical expression to a topic often seen as escaping language and representation: the Holocaust.

“More so than prose, modern poetry in particular forces us to reflect not only on what is said but how language itself operates,” Emden said. Poetry, he said, foregrounds the problem of how language represents the world in the first place — an almost philosophical pursuit, and one that prose doesn’t really tackle.

“By pushing poetic language to an extreme that often makes reading and understanding difficult, Celan emphasizes the autonomy of language vis-a-vis other forms of representation, e.g., images, paintings, film, et cetera,” Emden said.

The conference also coincides with the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, regarded as the symbolic end of the Holocaust, though Celan is not strictly a “Holocaust writer,” the conference organizers are quick to note.

Instead, Emden said, the real achievement of Celan’s poetic language is its ability to indirectly reconstruct lived experience — and thus humanity itself — at the intersection of something both resoundingly historical and deeply personal.

For these reasons, Celan’s poetry — indeed, all poetry, Emden said — maintains an urgency today as we seek to understand our place in the world and its ever-unfolding history.

A poet like Celan, Emden said, can provide “an understanding of the actual relevance of poetry and poetic language for the ways in which we, as human beings, reflect on what we are and on our position in this world — a world that is not rosy and simply marked by the empty pursuit of economic happiness, but a world that is serious and places existential demands on us, including demands of an ethical nature that cannot easily be resolved.”