Rice University researchers, alumni and staff are part of an international effort that has discovered a pathway for warm ocean water to melt the underside of Thwaites Glacier, a precarious body of west Antarctic ice that could add as much as 25 inches to global sea level if it were to suffer a runaway collapse.

In two papers published this month in the journal The Cryosphere, a team of U.S. and British scientists detailed deep seabed channels beneath Thwaites, which covers an area approximately the size of the state of Florida and is particularly susceptible to climate and ocean changes.

Glaciers are moving bodies of ice that flow downhill. Thwaites flows into the Amundsen Sea, and already accounts for 4% of global sea-level rise each year. The amount of ice Thwaites dumps into the ocean each year is five times greater than it was 30 years ago.

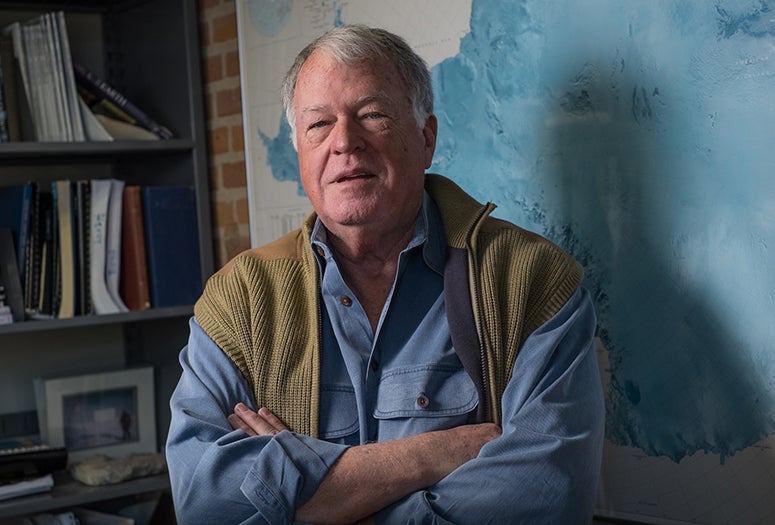

Rice Antarctic expert John Anderson, co-author of one of the papers, said the research brings attention to an impact of climate change that has gotten little attention in a year when the global COVID-19 pandemic competed for headlines with "unprecedented drought and wildfires in the west, record temperatures at the poles and what is potentially going to be a record year for severe storms and their impacts."

"History will record the year 2020 as one filled with eye-opening impacts of climate change," said Anderson, Rice's W. Maurice Ewing Professor Emeritus of Oceanography. "One example is global sea-level rise, which is occurring at about five times the rate of a century ago and causing significant impact on coastal areas across the globe."

It's well-established that ocean warming and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets are increasing rates of sea level rise. The melting of thick ice sheets atop Greenland and Antarctica have the most potential to increase sea level, but scientists still do not understand all the factors that influence ice sheet stability. Thwaites is especially remote and little studied.

"The Greenland Ice Sheet shows clear signs of accelerated decay, with vast areas experiencing melting and retreat that is clearly observed from space," Anderson said. "But, melting of the Antarctic Ice Sheet has remained more elusive because the ice sheet is melting from its base and is less obvious to scientists."

Thwaites is part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which is about two miles thick and sits mostly on land below sea level. Because water extends far beneath Thwaites, it is particularly vulnerable to a runaway collapse, which occurs when a glacier lifts off the continent and slides into the ocean.

Because Thwaites has the potential to increase sea level so much, the United Kingdom and the United States have funded a joint effort, the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, to study the glacier in detail. The two papers published this month resulted from the collaboration's first data-gathering missions in January-March 2019.

Anderson, a veteran of more than two dozen Antarctic expeditions, is a member of the collaboration's Thwaites Offshore Research (THOR) project, as are three former members of his research group – Julia Wellner '01 of the University of Houston, Rebecca Totten Minzoni '14, of the University of Alabama and Lauren Simkins of the University of Virginia. Rice science writer and photographer Linda Welzenbach, a science communications specialist in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, is also a THOR member.

Minzoni and Welzenbach sailed with THOR aboard the National Science Foundation icebreaker Nathanial B. Palmer in 2019 to map the seafloor in front of the glacier. Welzenbach served as the mission's public outreach coordinator and photographer. THOR's maps revealed networks of deep-sea channels that allow water from the Amundsen Sea to reach the cold underbellies of both Thwaites and its neighbor, Pine Island Glacier.

"This discovery is an important step in estimating the volumes of water, and therefore heat, that are reaching the ice," Anderson said. "Scientists need that information to predict future ice loss and associated sea-level rise."