Gerilyn Gordon’s grandfather was greeted at the Port of Galveston in 1901 with a banana. It was a welcome gift for the new immigrant from his brother-in-law.

The young man from Austria had never seen a banana before and didn’t know if it was kosher, but he recognized the exotic fruit as a harbinger of an exciting future in America.

Indeed, he was so thrilled to arrive in Galveston that he never left — “never even wanted to cross the causeway,” said Gordon, who works in Rice’s Office of Finance.

But most of the 10,000 Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who arrived through the port as part of the “Galveston Movement” between 1907 and 1914 fanned out across all of Texas and the rest of the nation.

As Gordon’s grandfather and, a few years later, her grandmother settled into life on the island, mementos occasionally sent from back home reminded them of their difficult decisions to leave the old world behind.

“Every year they got a picture from Europe, and that's how they knew when somebody died — that person was not in the picture anymore,” Gordon said, recalling her grandmother’s stories. “She sat shiva when her mother disappeared from the picture.”

A Jewish immigrant's guide to Texas

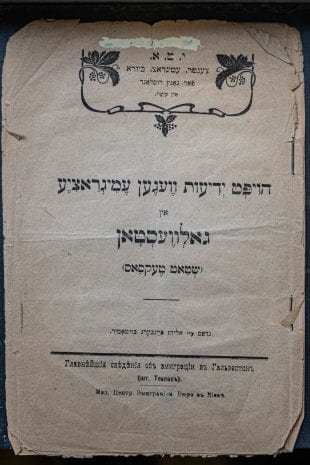

Anecdotes like these serve as reminders of the individual immigrant stories of the Galveston Movement — as do primary source documents like the rare guide to the immigration process obtained late last year by Joshua Furman for the Houston Jewish History Archive located in Fondren Library's Woodson Research Center.

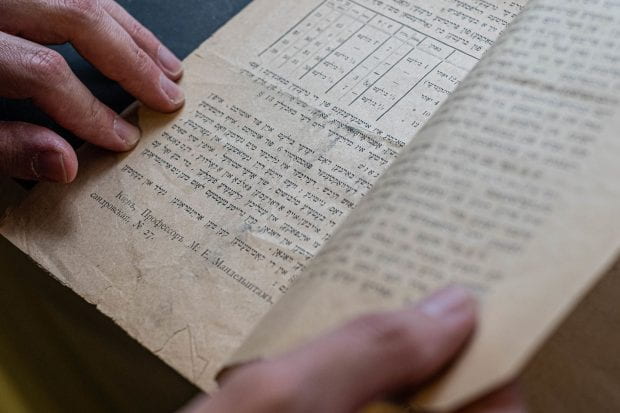

The delicate pamphlet is one of only two known to exist, printed in 1907 in Ukraine, mostly in Yiddish. The other pamphlet had never been translated, and when Furman heard that this one — tucked away in the collections of a rare Judaica book dealer in New York City — was up for sale, he rushed to obtain it.

Soon, the pamphlet arrived in Houston, where it was translated by Maurice and Judy Wolfthal. Their work revealed a guide to Texas — home to 20,000 Jews at the time — that was remarkably accurate.

It described the jobs available in various Texas cities, the Jewish populations and institutions found there (Houston’s population of 60,000 included 2,500 Jews), what to expect upon arrival at the Port of Galveston and honest assessments of the weather: “Except for its southern section, its climate is good for your health, especially in the winter months.”

For Furman, it was a tremendous find.

“Now we have the document that would have convinced people who live in a shtetl, in a small village, in Eastern Europe in 1907 — what do they know about Texas? — to try to entice them to make this incredible journey,” Furman said.

Though it only took place over seven years, the Galveston Movement had an outsized impact on the Jewish diaspora in the United States.

Most Eastern European Jews came to American through Ellis Island. But in the decade before World War I, a wealthy Jewish philanthropist in New York City, Jacob Schiff, recognized a need to rescue the Jews from the pogroms spreading across Russia and Poland.

“He didn't want them to make that Ellis Island journey because he was worried that if the Lower East Side of New York became too overcrowded with Yiddish-speaking Orthodox or socialist Jewish immigrants, it would give more fodder to anti-immigration advocates in Congress,” Furman said.

“So the idea was to send these immigrants into the heartland of America where they would not be noticed by xenophobic immigration opponents and where they would find employment, find physical safety and assimilate into American life,” he said.

Ellis Island. And so, Schiff’s guide instructed Jews from across Eastern Europe to first travel to Bremen, in modern Germany. There, they waited in kosher-friendly lodging run by a network of Schiff’s fellow philanthropists until the next ship took them on a nearly monthlong journey to Texas.

From Galveston, extensive networks of train lines shuttled new arrivals to towns as close as Marshall and Temple and to states as far away as Rhode Island and California.

“He must have seen a pamphlet just like this.”

Paula Sanders’ great-grandfather was part of that Galveston Movement, arriving in 1911. He eventually joined other family members in St. Joseph, a town north of Kansas City on the Missouri side of the line. Older members of the tight-knit Kansas City Jewish community, Sanders said, still referred to the port city as “Gal-VES-ton,” a classically Yiddish emphasis on the penultimate syllable.

“When I interviewed for my job at Rice, I said, ‘You know, I actually have Texas roots,’” said Sanders, professor of history and director of the Boniuk Institute for Religious Tolerance. She had just finished reading a copy of the translated pamphlet, which will soon be published in the journal Southern Jewish History.

“I knew my great-grandfather came on a ship from Bremen, but I didn't realize until I read this that he was responsible for getting himself there,” Sanders said. “How did he get himself to Bremen? He must have seen a pamphlet just like this.”

For Furman, the pamphlet will help shed even more historical light onto similar questions about the journeys these men, women and children decided to undertake.

“What did they think they were getting into?” Furman said. “Right now, we have some information about that — we've got some memoir literature, some newspaper articles in the American press — but this is one more piece of the puzzle that we didn't have before.”