In 1962, the Rice Board of Trustees passed a resolution to amend its 1891 charter and desegregate the university, a change it would ultimately defend in a lawsuit that reached the Texas Supreme Court in 1967. But Rice’s move to admit Black students was a decision spurred mainly by financial and aspirational motives rather than a commitment to advancing civil rights.

Putting the landmark legal case into context was the focus of a Nov. 5 webinar that explored how pressure to “do the right thing” was only one factor in Rice’s decision to desegregate. The move was immediately opposed by alumni, who filed a lawsuit to block Rice from changing its charter and thus prevent Black students from attending.

Hosted by Rice’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice, “The Legal Battle Over Desegregating Rice” webinar convened panelists with Rice roots and a wide range of legal expertise.

Moderator Akilah Mance ’05 is the general counsel for the Houston Forensic Science Center, an independent crime lab serving the city of Houston and its police department. Her panelists were Megan Francis ‘03, associate professor of political science at the University of Washington; Steven Wilson ’86, assistant provost of academic affairs and registrar at Lehigh University; and Michael Olivas, the emeritus W.B. Bates Distinguished Chair in Law at the University of Houston Law Center.

The legal battle, Wilson said, “wasn’t what we would now regard as a civil rights case at all.”

“It didn’t have the hallmark of plaintiffs seeking entrance to Rice,” he said. “It didn’t have the sort of arguments that we see in other civil rights cases… There was no reference to the 14th Amendment.”

Wilson described Rice in the early 1960s, when the original petition was filed by the Board of Trustees, as a campus that had just signaled its greater ambitions by changing its name from Rice Institute to Rice University. (Alumni had opposed that, too.) The newly renamed university was 50 years old and had recently appointed Kenneth Pitzer as its third president.

“He was hired by the trustees to transform Rice into a major player in higher education,” Wilson said.

The Cold War era, he said, was both “an exciting and dangerous time to be in higher ed.” But Pitzer’s bold plans — a tenure system, new laboratories, more robust graduate programs and the kind of research output that would attract world-class scholars — would match the big strides undertaken by Space Age America.

Due partly to the fact that it was then a tuition-free institution, Rice was perceived as a wealthy school. Yet as early as the 1920s, the trustees recognized they needed to secure more funding. The Great Depression and successive World Wars mostly stymied fundraising efforts, but by the 1960s a booming country was investing heavily in higher education.

The federal government was handing out the kinds of grants Rice needed, but many of those grants came with caveats requiring that their funds go only to universities that had desegregated and which charged tuition. Rice needed that federal money to continue pursuing fruitful relationships with government institutions such as NASA, the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. The trustees knew Rice would eventually need to charge tuition anyway in order to continue achieve its ambitions.

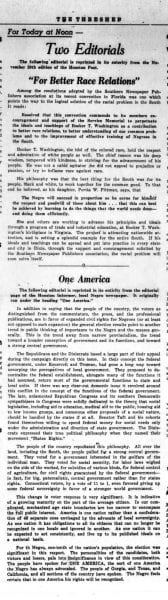

Meanwhile, as early as 1948, Rice students had begun calling for the campus to follow the example of the U.S. armed forces by desegregating. That same year, the editorial board of the Thresher, Wilson said, “was making the argument that Rice should be at the forefront of this — that Houston is going to be a great city and if we do this, Rice will be a great place, too.”

Ivy League institutions were ahead of other colleges by this time, Francis said: Yale’s first Black student graduated in 1857; Alpha Phi Alpha, the first Black men’s fraternity, was founded at Cornell University in 1906; even the southernmost Ivy, Princeton, graduated its first three Black students by 1947.

“Even in terms of the ’60s,” Francis said, “Rice was moving at a glacial pace.”

Houston’s only public university at the time was Texas Southern University (TSU), as the University of Houston went private in 1945. And in 1950, TSU had been at the center of landmark “separate but equal” case Sweatt v. Painter, which would later be crucial to deciding Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

“Of course, with this landmark decision, the Supreme Court held that segregation in public education violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment,” Francis said. “The Brown decision inspired student marches across the country, and especially in the south. But they also advocated inside and outside the hedges; segregated institutions of all stripes needed to fall.”

By 1960, TSU’s students were organizing the city’s historic sit-ins — the first west of the Mississippi — at Weingarten supermarket lunch counters. By 1963, the University of Houston was undergoing desegregation in order to become a public institution once again, leading to the rise of such student groups as Afro-Americans for Black Liberation.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had not yet passed, but across the country, organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee were leading protests and marches and changing hearts and minds.

“The grassroots civil rights movement created a national crisis of conscience that led many individuals and institutions vital to colleges’ survival to insist on desegregation,” Francis said.

Even the city of Houston itself had begun undergoing desegregation in its own unique fashion: Newspaper owners secretly agreed to a total blackout of press coverage, making for a quiet transition in schools and other public spaces throughout the 1960s. Houston avoided the unrest that convulsed other cities like Little Rock and Montgomery.

“And so these things came together — the tuition issue and the civil rights issue — and that’s what led, finally, in the early 1960s, for the trustees to finally decide they were going to try and change the charter specifically so that they could do these two things,” Wilson said.

Yet what should have been a relatively simple matter, he said, quickly turned into a legal morass as angry alumni challenged reformatting the university’s charter.

“One of the most interesting things about this is how a very carefully articulated and planned and strategic case, which was just supposed to be saluted by everybody, turned out to be as vexed as it was,” Olivas said.

The original petition to desegregate the university and charge tuition was filed with the courts in 1963. It was countered a few months later with a lawsuit filed by alumni John Coffee and Val Billups. In January 1964, another group of alumni filed a petition supporting the trustees’ position and opposing Coffee and Billups. The case went before District Judge William M. Holland’s court in February 1964 and a verdict favorable to Rice was handed down the following month.

But Coffee and Billups weren’t done: After losing a series of appeals in lower courts, they eventually took their case to the Texas Supreme Court. It all came to an end in 1967, when the original 1964 ruling in favor of Rice was upheld once and for all.

Stranded amid the chaos was the university’s first Black student, who had been admitted in 1963 but was left “waiting in the wings,” Olivas said, for years while the case wound its way through the courts.

“Dr. Raymond Johnson, the very first Black student to attend and graduate from Rice, he’s here,” Mance said. “He’s come to Rice understanding and believing that he’s going to be a student. And as he’s beginning his coursework, that fall, he gets a notice from the university: Pause while we work this out with the attorney general.”

The delay behind them, Rice could finally move forward with admitting Johnson and all of the Black students who would follow in his footsteps. And this, the panelists all agreed, was a necessary step towards making Rice the world-class university it now is.

“This was instrumental in a very direct way to becoming a better institution,” Olivas said. “Because having access to the best students in the world is what distinguishes Rice today.”

Francis, who spent much of her undergraduate time at Rice involved with organizations like the Black Student Union and hopes to see even more Black students at Rice in the future, agreed.

“It’s always been the case to me that we make these institutions better,” Francis said.

And although the panelists agreed that Rice never held itself up as an example of a particularly progressive institution at any point in the civil rights era, the end result is clear: The legal battle did land Rice on the right side of history.

“These were good, sound steps for the aspirations that Rice had,” Wilson said.

Pitzer, too, deserved credit for his role in desegregating Rice, he said.

“It shows the value of a president and a leader who makes his job contingent upon doing this, and then does it, because it would have set the university back 20 years if he had not,” Wilson said.

“The narrative here actually is a very fortunate and positive one that people should be proud of, even if it were undertaken for the wrong reasons,” he said. “Sometimes great things occur for all the wrong reasons.”