What is it to be a Black student at a predominantly non-Black institution? Black undergraduates at Rice laid bare their thoughts and frustrations in a sweeping discussion via Zoom Oct. 22.

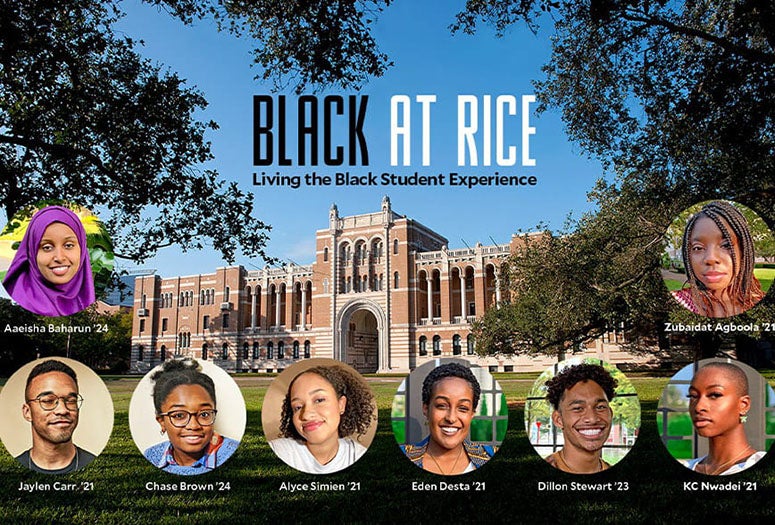

“Black at Rice: Living the Black Student Experience” was convened by the university’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice and moderated by Duncan College magister Eden King, the Lynette S. Autrey Professor of Psychology.

King began by addressing the fact that, as a non-Black person, she couldn’t speak directly to the evening’s topic.

“But I hope like many of you, I am here to listen — to really listen — to learn and to do my best to support Black students at Rice,” King said.

One major theme shared among the panel’s participants, who ranged from freshmen to seniors across five of Rice’s residential colleges, was a desire to be more forcefully heard and for their concerns to be more widely recognized.

“One-hundred percent honest, I feel like there's a little bit of frustration amongst some of the Black students just because I feel like we did lay out a list of demands, and a lot of those demands haven't been met,” said McMurty College senior Alyce Simien. She noted that the task force, for instance, was not on that list of "Tangible Ways to Improve the Black Experience," which students issued over the summer.

“I do think Rice could have easily have done nothing as well,” Simien said. “So we are definitely grateful for everything that occurs. But I think there is just a little frustration in feeling like, you have to be grateful for the bare minimum.”

Students also felt that, despite ongoing achievements around diversity at the university, they still bear much of the burden of continuously integrating the campus and educating their fellow Rice community members.

“When I came in as a freshman, and even as a sophomore, I saw so many Black upperclassmen who were working so, so hard to just improve the campus,” said Zubaidat Agboola, who later threw herself into similar work with organizations such as the Black Student Association (BSA) and the Rice African Student Association (RASA).

Agboola and Duncan College senior Axel Ntamatungiro co-founded a task force focused on "Increasing African Presence in Academia" in part to advocate for an African studies major. They organized events educating others about such topics as “Western Misconceptions of African Reality,” a discussion held during last year’s Black History Month, all while juggling the demands of coursework.

“That's extra pressure on you as a student to, you know, fix systematic problems that have been here (at Rice) since Black people have been here — and in the span of your four years — plus do academics, plus do extracurriculars,” Agboola said. “It's just a lot of stress to put on a group of people, a small group of people at Rice.”

Many students are also athletes or have jobs in addition to their classes, and it can be exhausting to handle it all while simultaneously struggling with the mounting grief presented by the current racial climate across the globe.

“I don't know how explain it — my people are dying,” said Wiess College senior KC Nwadei. “I'm Nigerian. I was born in Nigeria. And my family, my people, are dying and being murdered and killed,” she said, referring to ongoing violence and deaths amid protests against police brutality in the West African nation. “And I'm just supposed to sit in class while everything is going on over there.”

Agboola, whose family is also from Nigeria, agreed.

“You see Black people all over the world dying from police brutality,” she said. “It's been a rough couple of weeks, especially for my people in Nigeria and all over Africa.”

“And those things that people think happen outside of Rice, outside the hedges — they happen in the hedges too,” said Nwadei, who recounted instances of hearing racial slurs, racist jokes and frustrating interactions with non-Black students.

“I feel like after freshman, sophomore year, all the Black students move off campus — and it sucks for the freshmen because they don't get to see Black upperclassmen but it's like, at what cost are they going to like stay on campus when it's an everyday thing?” she said. “Walking around and not seeing people that look like you … you feel kind of lost and on the outside of everything.”

And when she and her fellow Black students would gather for meals or other social interactions, Nwadei said, bizarre assumptions would follow.

“This happened so many times: Me and my friends would get together, it doesn't matter at what college, and people would be like, ‘Oh, what club meeting is this?’ Why did you expect it to be like a club meeting, for it to be RASA or BSA? We just can’t be regular students,” she said.

When you’re seen as Black first and foremost, which can happen at a university where Black students make up less than 10% of the undergraduate population, there’s pressure to both be the Black voice in the room and “represent the race,” as it were.

“I would want faculty — everybody at Rice — to know that I'm always conscious of the fact that I'm Black,” said Baker College freshman Aaeisha Abdurahman Baharun. “In some cases, it's positive; in most cases, it's in its negative form — I'm worried that people are looking at me or, like, ‘Am I representing the whole race well?’ I’m just one person. I just want to be myself.”

Among the racially motivated remarks many of the students reported hearing over the years was the insinuation that they were only at Rice because they were Black.

“I can't even tell you how many times at Rice I've heard jokes and comments about Black students having it easier to get in and complaining about (how that) doesn't allow other people who deserve it more to get it,” Simien said.

“I've had to sit in a philosophy class where we debated whether that was true or not. Maybe it's just a fun debate for you, but it’s traumatizing to have to go through that in class and just sit there and listen,” she said.

Baharun agreed, adding that she shares a lot of the same self-doubts many students naturally bring to their college experience.

“Sure, I might have clicked the box saying ‘African American’ on the Rice form, but I would like to believe that they chose me for more than that,” Baharun said. “And I’m already suffering with imposter syndrome — you don't have to throw that at me too.”

Students said that while they feel supported by most faculty and staff, there are still too many incidents in which Rice community members don’t intercede and should.

“The amount of racist jokes I hear on a daily basis … it kind of blows my mind, thinking that we go to a school that like prides itself on having the happiest students, prides itself on its diversity and inclusion,” said Wiess College sophomore Dillon Stewart.

“Yet I've had experiences where I will hear a racist joke, I'll confront it, and there will be an adult standing right there, hearing it and saying nothing,” he said. “And it's like, am I having to fight this battle by myself?”

Equally troubling, said many of the students, was the idea that the recent surge of support for racial justice movements, both at Rice and in the world at large, would end up being brief and conditional.

“If that sort of conversation just naturally hits its turning point or it fizzles out, then people will suddenly be like, ‘Oh, well, like things are good now,’” said Martel College senior Jaylen Carr.

“And then we won't be having these discussions about further developments that are needed — they're necessitated by the current conditions of not only the country, but of Rice,” he said. “And so I'm anxious, but also hopeful that we are going to continue to have this discussion for years to come, for as long as it takes, far beyond us.”

At the beginning of the conversation, Catherine Clack, the associate dean of undergraduates and director of the Office of Multicultural Affairs, shared some of her own context and history after nearly 40 years at Rice.

In 1981, the Black student population had been so small, Clack said, that every single Black student, faculty and staff member was on a first-name basis. Areas of weakness had long been identified, and campus groups across the country like the Students of Color Coalition would form to address many of those concerns.

After the current students shared their thoughts, Clack said that what she was most impacted by was the fact that a lot of the concerns and issues students are conveying today are the same she was hearing on campus 20 to 30 years ago.

“To be honest with you, I think that it's just always going to be distressing to hear that there's still a significant cohort of your population who just isn't finding the sort of connection and support on an emotional, mental and social level that contributes to a well-rounded, healthy college experience — and one in which you can look back fondly, and therefore you become that outspoken, delightful alum who's getting everybody else to go and who's invested in the university,” Clack said. “And I know that we are keen on making sure students are always feeling invested in part of the university.”

One of the most important ways to address this, the students said, was to not only listen to their concerns, but share them with others.

“I was honestly so captivated by what everybody was saying and resonating so much with what everybody was saying, I forgot I was on the panel,” said current RASA president and Sid Richardson College senior Eden Desta, who implored everyone watching to share the video of the evening’s discussion and remember that Black students, despite sharing similar experiences, are not a monolith.

“We're not one group. And the only way you're going to get that idea is if you listen to a lot of different people, because not one person has had the exact same experience as another,” Desta said. “I think that's very important, as is sharing and echoing our stories.

“Watch this recording, share this recording. Black people are being vocal — so vocal — right now. Just echo our voices and don't overpower them.”