Ahead of a typical study-abroad trip for Rice in Japan, professor Naoko Ozaki tells her second-year Japanese students to prepare a recipe they’ll be able to make using ingredients found in Tokyo or the countryside town of Fujieda, Ozaki’s hometown. Making a meal is a fun way to literally share a taste of their own culture and, just as importantly for Ozaki, to show gratitude to their hosts in Japan.

The pandemic, however, forced the Rice in Japan program to cancel its yearly summer trip and instead take the JAPA 263 course to Zoom. Of course, an online classroom can’t replicate everything about a study-abroad trip — including shared meals with locals — but that didn’t deter Ozaki.

“I will do my very best to bring Japan to you,” Ozaki promised her students. “I'm Japanese enough for all of us.”

And through their final project, an online cookbook of cross-cultural recipes translated into Japanese, Ozaki and her class were able to send a little bit of Rice to Japan.

From Turkish cheese pastries and Indian-style scrambled tofu to Salvadoran pupusas and French-influenced duck confit, each recipe was compiled by a different student, who wrote a personal introduction explaining the dish’s background and significance. The recipes were narrated in Japanese by the students who chose them, a component designed in lieu of a traditional oral exam.

Once completed, the online cookbook was shared with the people who’d helped Ozaki’s class virtually replicate a summer abroad.

“It's important for my students to know that they have to show gratitude; they cannot be just the takers,” Ozaki said. “These Japanese people helped, and I didn't pay them any money. So I told my students, ‘This is what can we do in return.’”

What can we do thanks to Zoom?

Ozaki and her students were naturally disappointed when they realized their trip would be canceled. But Ozaki said her perspective shifted quickly after she began hearing the phrase, “Thanks to Zoom … ” spoken with sarcasm, not sincerity.

“I said, ‘OK, what can we do because of — or thanks to — Zoom?’” Ozaki said.

That’s when she started reaching out to her fellow Japanese professors across the state — Ozaki is the president of the Japanese Teachers Association of Texas — and to her Japanese friends both here in Houston and back home in Fujieda, a small town in Shizuoka Prefecture near Mount Fuji.

After making sure her students would be OK with Zoom calls in the evening, Ozaki planned a seven-week summer session filled with the kinds of sociocultural exposure crucial in a study-abroad trip.

Her students learned the art of paper cutting and crafting bento boxes from Japanese experts. They Zoomed with people whose Osaka and Kyoto dialects were distinct from the Tokyo dialect that’s more common in Japanese media while friends from back home in Fujieda also served as guest speakers. The class chatted in Japanese with fellow students at Texas A&M whose summer plans had also been curtailed. Ozaki’s young nieces and nephews talked to them about their daily lives in Yokohama and Marugame over Zoom, fondly referring to the Rice students as their “big brothers” and “big sisters.”

“The great thing about this class was that in terms of the actual learning and the engagement, it was the exact same as it would have been in person because Dr. Ozaki is so engaging and always had fun stories to share,” said Wiess College junior Pranay Mittal.

A computer science and mathematics double-major who became interested in Japanese after years of listening to J-rock and other Japanese music back home in Seattle, Mittal had taken one of Ozaki’s first-year courses and was eager to take a trip abroad with the professor. But, he said, the fact that the class ended up going virtual didn’t detract from the experience.

“There were just so many things we did that were only possible because we established Zoom as a precedent from the beginning,” Mittal said. “Like, we were able to talk to all of these people around the world.”

A cookbook unlike any other

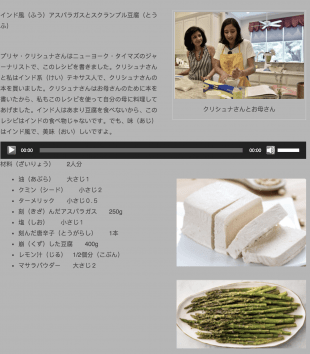

Mittal chose his recipe, Indian-style scrambled tofu with asparagus, in part because the ingredients — save, perhaps, the masala spice — would be easily found in Japan. But what made it personal was that the recipe’s original author, New York Times writer Priya Krishna, was also an Indian American living in Texas.

“I was drawn to this recipe because the author made it for her mom and so I made it for my mom on Mother's Day,” said Mittal, who was already a practiced cook and enjoys experimenting with recipes. The toughest part, he said, was translating the ingredients and steps into Japanese. It was a complicated recipe, but Ozaki cheered him every step of the way.

What impressed Mittal the most was the diversity of recipes submitted by his classmates, some of whom even took the time to translate the recipes into other languages, such as Russian, Chinese and Turkish.

“It's hard for me to imagine a cookbook that's so, like, out there, you know?” Mittal said. “These American students writing about their cultural dishes in Japanese. It was just a really fun experience.”

His other big takeaway was what Ozaki had hoped to instill in her students all along.

“The Japanese culture is very big in terms of expressing gratitude formally, but I think it’s something that Dr. Ozaki really wanted us to internalize and express when it came to all these other people who came together to help make these events possible,” Mittal said.

And the recipes, Ozaki said, are already being employed by her friends and family back in Japan.

Her sister, she said, was experimenting with one student’s recipe for Cameroonian “drop doughnuts.” Her father has been leaving encouraging comments on all of the recipes and is planning to make the Turkish lentil soup. They’re all eager to meet Ozaki’s students next summer, when Rice in Japan hopes to return once again. Many of Ozaki’s students in this summer’s course plan to make the trip with her.

“I’m excited too,” she said. “I’m looking forward to it.”