By Andy Olin

Special to the Rice News

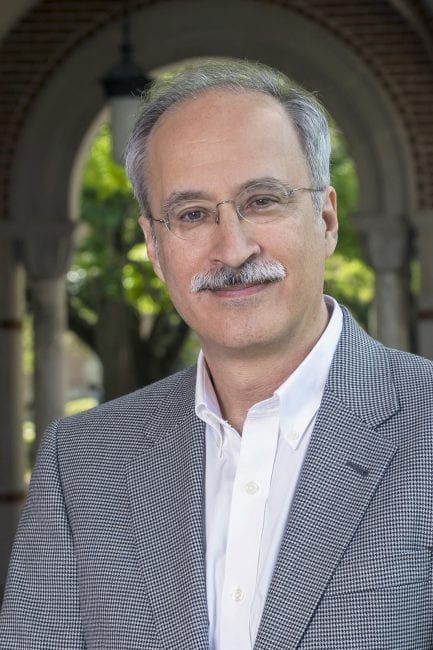

"When you think about an urban environment, which is densely populated like Houston, you have really specific challenges, as we've seen on cruise ships," said Yousif Shamoo, Rice University's vice provost for research and a professor of biosciences, on efforts to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, the pandemic spreading throughout the United States and changing life as we know it. "If you look at the Diamond Princess, that's kind of the worst-case scenario in terms of infectious disease because cruise ships essentially are a petri dish. And when you have an infection, they're really difficult environments."

Shamoo is an infectious disease expert and researcher who studies multidrug-resistant bacteria. ("Those super pathogens that you hear about in hospitals, like MRSA — Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus — things like that, which are resistant to almost all antibiotics," he said.) And he's explaining how infectious diseases such as the coronavirus threaten and can quickly accelerate in urban areas like Houston.

COVID-19 is a viral — not bacterial — infection but, as Shamoo points out, the characteristics of transmission and how they move through a community basically are the same for viruses and bacteria. "Not exactly the same, but they're pretty similar," he said.

"On the other hand, if I'm a rancher in Montana, I might see somebody tomorrow or I might not. So, density matters," he said. "The persistence (of the virus) in the environment matters.

"Cities are densely packed and we have lots of mixing of the community. And that makes containment really difficult. Right now, in the United States, we've gone from containment to mitigation. As you've heard Dr. (Anthony) Fauci (head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases), say, containment happens when you're in the mindset of 'we're going to stop the infection at the gates. We're not letting anything through.'

"When things start getting through — as we have now — you have to transition to mitigation."

“Here’s what I think about Texas, in particular: People here, when they’re told the right things to do, generally, will do them.”

Houstonians have shown resilience in the face of crises

Shamoo is also a member of Rice's Crisis Management Team, which has taken a series of preemptive steps to address the virus and protect the health of students, employees and the larger community. These included the March 12 decision to move all classes online for the remainder of the spring semester and the March 17 decision to reduce the on-campus staff population from 2,700 to approximately 300 at any given time.

"Rice was very proactive very early on and we were ahead of the curve in a lot of respects with regard to other how other universities were dealing with the coronavirus issue," Shamoo said. "But it helped that we're used to (natural disasters) like hurricanes. We know how to act — and react.

"And I think the city is the same way because we have been subject to crises on a regular basis. Maybe that's part of what's special about Houston. I would guess Houston has a significant psychological and infrastructure advantage in dealing with crises."

Shamoo originally is from New England but has been in Houston for many years — long enough to have witnessed the city and its residents respond to and recover from the sudden shock of disaster again and again.

"Here's what I think about Texas, in particular: People here, when they're told the right things to do, generally, will do them," he said. "I remember when Hurricane Ike hit the Gulf Coast in 2008 and Judge (Ed) Emmett said, 'Everybody hunker down.' And everyone in the city knew what that meant. And everyone pretty much did that, and the city was extremely disciplined in taking his advice.

"When people have the facts and when they understand the (seriousness of the situation), I think they will act accordingly. And I think you see it already.

"That doesn't mean people won't panic-buy toilet paper, which I still don't understand," he said. "Of all the things I would panic-buy, I'm not sure toilet paper is on that list."

As the nation works to slow the acceleration of the outbreak, Shamoo sat down to discuss the infection, what's being done to "flatten the curve" so hospitals and the health care system aren't overwhelmed, and what we can expect in the coming months.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

What's the difference between containment and mitigation?

If you have one individual in the city of Houston who had contact with somebody who was COVID-19 positive, then you can ask, where did they go? Who did they talk to? And you can quarantine all the people that they talked to that day, if it's possible. For the average person, you went to work, you talked to people, you went home to your family. You can quarantine those people. And that's containment. You're building a firewall around that first patient zero.

Once we have, say, 50 people, well, then the number of people that have contacted is in the thousands. You can't really identify all the contacts they've had. You don't have the manpower to interview all of those people. So you go to mitigation, which is to reduce the spread. And the easiest way to think about mitigation is just social distancing. You just put people farther and farther apart from each other. And that reduces the probability that they're going to transmit the disease from one person to the next.

How does Houston's size and density affect how we deal with an outbreak?

The incubation period of the virus, depending on the report you read, is somewhere between five and seven days before you become symptomatic. If you think about it, if all of us went home and sat in our rooms for two weeks, it's over. Because it didn't have anywhere to go. So, it got the people sick it was going to get sick and they got better — hopefully. And then it's done.

Now, can you do that in a city the size of Houston? No.

That's because food has to come in. People have to keep the power grids running. Social services have to be there. The medical system has to run, right?

Yes, in theory, everybody could go home and stay home for two weeks but who's going to treat the people who are sick? And health care workers who are exposed are becoming positive from this disease at a very high rate because — of course — it is very infectious. They're in close contact with those people all the time and heroically trying to keep them healthy. They're a very high-risk group, as are first responders who are transporting patients to the hospital.

So, many cities are tough environments for mitigation.

"... it can be shocking that in the space of three days, you go from this very small number of cases to a very large number of cases. But it will. That's the math. That's how these things — from the biology point of view — work."

What are we doing right?

I think the city has responded appropriately. Canceling the rodeo was a very difficult decision — but the right one — because there are economics and people's livelihoods to consider. If people stop going to restaurants or stop going to buy things, there are economic consequences that shouldn't be ignored.

Education is a big part of it. Teaching people to wash their hands; bump elbows instead of shake hands. You know, just have good hygiene. It's amazing how important hygiene is in all of this.

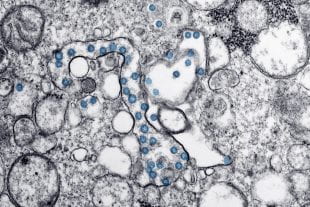

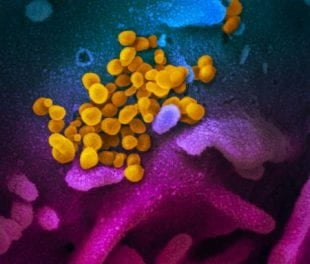

But it's not perfect because the virus can persist in the environment. It can stay on plastic surfaces and stainless steel surfaces. It's even aerosolized and persistent in air for a couple hours. There's some very nice work on this in review at the New England Journal of Medicine suggesting that the virus is airborne for a couple of hours at a time. That makes it really hard to be perfectly clean all of the time."

Where have we come up short?

I think the U.S. squandered a lot of time. Nationally, we were aware of what was going on in China for four months and watched it from afar.

As a person in this field, I feel like we didn't use the time to get ready. You can see that by the failure to test. We're testing a fraction of what other countries have tested and we're the most advanced country in the world (in terms of) biotechnology and biomedical applications. Yet, in this critical moment, we seem very flat-footed. And I think when we're all through this, there's going to be a serious reexamination of how we've handled this pandemic. And I don't think it's going to be very flattering.

What sort of things do we need to do now as we play catch-up?

You don't want people who suspect they have coronavirus going to the emergency room, right? You don't need to overwhelm the emergency room and contaminate all the emergency room doctors because you have a fever. So, drive-through or drive-up testing is promising. (More than 10 states now have drive-up testing sites.) You drive up in your car, you report your symptoms, "I'm not feeling well today; I think I have a fever." Someone takes your temperature really quickly, and, say you do have a fever, they'll swab you right there in the car. You open your mouth, they swab you and put it in an envelope and then they get back to you with the results.

So, you can begin opening up ways to get people tested so that they can know they need to quarantine themselves or stay away from elderly people. This is a disease that really hits older citizens much harder than younger citizens. So, say grandma is living with you. Well, you know you need to distance yourself from her.

Or, if you have somebody in your family with an underlying medical condition that makes them immuno-compromised, you need to not be around them. And that's challenging but COVID-19 spreads very well in a family cluster because we're in close proximity to each other.

"We're testing a fraction of what other countries have tested and we're the most advanced country in the world (in terms of) biotechnology and biomedical applications. Yet, in this critical moment, we seem very flat-footed."

What should we expect next?

You know, one of the other dynamics that people aren't used to is the rapidity with which the disease will spread. As animals, we're not really good at understanding doubling or exponential phenomena — things that go really rapidly. So, things look fine. Things look fine. And then, "holy cow, things don't look fine at all now."

Intuitively, we don't see phenomena like that very much in our day-to-day existence. We tend to be linear thinkers — it got a little bit worse, it's incremental, incrementally worse. We don't expect doublings to happen or exponential growth to happen this way. And so, it can be shocking that in the space of three days, you go from this very small number of cases to a very large number of cases. But it will. That's the math. That's how these things — from the biology point of view — work. It would be surprising if it didn't go that way for the United States.

Now, I hope that because we're aware of what we need to do, that will help. People are doing a lot of social distancing on their own. Public health is always about what the public does. The government can only do so much to educate and provide resources. At the end of the day, it's about how well you and I take responsibility for ourselves. Do we wash our hands? Do we avoid doing things we don't need to do?

Is there a way to estimate how many people in the Houston region will end up contracting the coronavirus?

Oh, I can make estimates but I'm not an epidemiologist. I'm sure the city has their estimates. A lot of it depends on how often and how aggressively we test when it comes to how accurate those numbers are going to be.

There's a certain inevitability that will have to play out over the next couple of months. If you look at what's happened in the countries that have preceded us or are currently at high stages of infection, that's how it will play out here in some ways. You hope that it's not Italy. You hope it's more like South Korea, which did a good job of controlling it but still had a large number of infections.

What you want to do by your public education mission is to get everybody pulling on the same team, mitigate the spread of the disease and then you can get to a more controlled crash landing as opposed to the crash landing.

Andy Olin is a senior editor and writer at Rice University's Kinder Institute for Urban Research