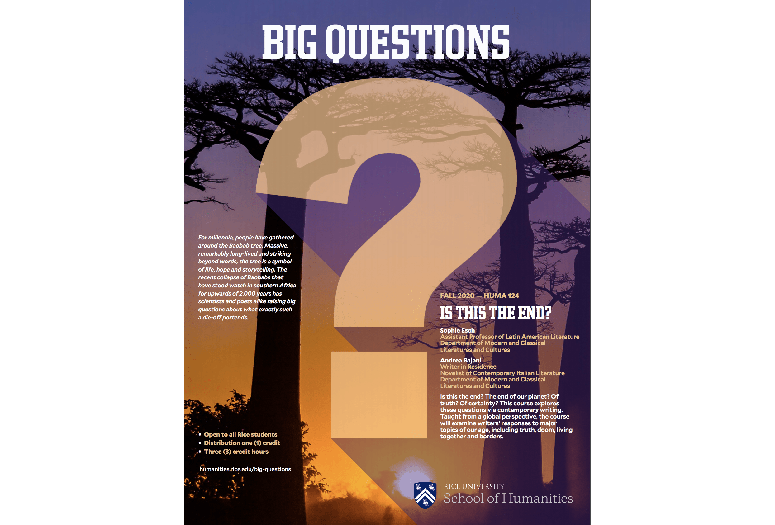

The groundbreaking Big Questions courses from Rice’s School of Humanities are designed to take a multidisciplinary approach to some of the most compelling and interesting questions of our time. And this semester, those questions are more topical than ever.

“Is This the End?” will be taught by assistant professor of Latin American literature Sophie Esch and Andrea Bajani, one of Italy’s foremost modern novelists and current Writer-in-Residence at Rice. “What Is the Ethical Thing to Do?” will be taught by philosophy professor Elizabeth Brake.

Both classes are filling up quickly, and not just because they’re distribution courses created to be accessible for all students at Rice, regardless of major. There’s something compelling about the freedom to explore questions for which there is no “right” answer.

“The School of Humanities is thrilled at the success of the Big Questions courses we have offered thus far,” said Dean of Humanities Kathleen Canning. “Our goal remains that of inviting students from across the Rice campus to grapple with big questions that are relevant across disciplines, professions and generations and to do so in the vibrant classrooms of our most exciting and accomplished teachers.”

In “Is This the End?” students will be prompted to think about how we identify a process, period or phenomenon that is coming to an end — whether that’s the end of truth, of democracy, of national borders or the end of the planet as we know it. And then there’s the matter of how to measure an ending.

“We always assume that the end is the end and it lasts one second,” Bajani said. “It can be reassuring to think, ‘Oh, it’s the end; it’s finished,’ but no — the end can be a long, long journey.”

The course will use contemporary literature from across the globe as a framework for examining these ideas, with writers hailing from Angola, Mexico, India, Italy, Germany, Belarus or Argentina. It was decision inspired by a chance hallway conversation last semester between Esch, a literary scholar, and visiting writer Bajani.

“Literature helps humans think about the world and through the world, so this is really a course about the current zeitgeist,” Esch said. The course will begin with one of the books she examines for her current research on animals, humanity and war. It is a novel by acclaimed Mozambican author Mia Couto, “Sleepwalking Land.”

“It's a novel about war and it's a novel about destruction,” Esch said. “But it is also a novel about trying to think about what happens after the destruction — how do you rebuild a country, how do you rebuild humanity after something like that — so it is a novel of both doom and genesis.”

In “What Is the Ethical Thing to Do?” students will probe this question as it applies to the fields of artificial intelligence, engineering and natural science. The course will introduce students to key philosophical texts on ethics while inviting them to consider applications of ethics to contemporary issues such as reparations for slavery.

“Most people want to do the right thing, but it's not always clear what that is,” said Brake, whose research as a philosopher has focused on the study of disaster ethics and states' role in disaster response.

“More information doesn't always help” Brake said. “For example, knowing how the coronavirus is transmitted can help us make more informed decisions, but doesn't settle questions about our moral obligations to sacrifice for the greater good and the degree of risk that it is morally acceptable to impose on others.”

There is, however, a long tradition of philosophical ethics which has investigated such moral questions, and this class will be an introduction to them. Students will also be introduced to classics of Western moral philosophy, while at the same time making cross-cultural comparisons and examining historical philosophers with a sensitivity to race and gender.

“For example, what should we make of the fact that John Locke, one of the most influential theorists of property rights, held shares in a slave-trading company?” Brake said.

In addition, there will be an “ethics lab” component, in which students will do in-depth research on an ethical question of their choosing, and the course will culminate with a sustained examination of arguments for reparations for slavery and racial injustice.

To that end, Brake has lined up a series of guest speakers for her course, from within Rice and outside as well. Susanne Sreedhar, associate professor of philosophy at Boston University, will speak on early modern philosophy and gender. George Yancy, Emory University’s Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Philosophy, will speak on racism from a philosophical perspective following an assignment of excerpts from his seminal book, “Black Bodies, White Gazes, The Continuing Significance of Race in America.”

Rice’s first faculty Pulitzer Prize winner, history professor Caleb McDaniel, will also visit with the class, and teaching assistant Wan Zhang — who’s currently pursuing his Ph.D. in philosophy — will give a guest lecture on Confucianism and virtue ethics.

Outside of the topics debated within the classes themselves, students will hopefully come away from these Humanities courses knowing that they can — and should — be asking these kinds of “Big Questions” in everyday life. Those critical thinking skills can be successfully applied across any and all pursuits, Canning said.

“Big Questions courses have the high ambition of providing students with the vital skills of critique — social, literary or philosophical — that will enrich their studies of science and medicine, law and society, humanities and the arts, and equip them to lead and shape the future,” she said.