As the COVID-19 crisis plays out, Rice University faculty have been proactively making the best of a difficult situation for their students — not to mention for themselves and their families — while navigating the daunting process of moving hundreds of classes online.

And so far, so good.

Some faculty come to campus to teach alone in web-enabled classrooms that let them give more traditional instruction. Some record hours of lectures at home and distribute them to their students, saving classroom hours for personal interactions via Zoom. That is, essentially, the flipped classroom model that became popular among some professors a few years ago, now made necessary by reality.

And did we tell you about the chopstick solution? Wait for it.

The Rice community has stepped up to deliver on promises and give every student as much opportunity as possible to complete their academic requirements, even when lab courses are strictly curtailed.

“This week, there’s been more of a lull, and I would say some kind of stability,” said Robin Paige, director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an adjunct professor of sociology at Rice, of the transition before and during spring break to online learning.

“One of the instructors I’ve been working closely with had a bunch of Zoom sessions with his students,” she said. “I sat in on one of those to do some problem-solving and then he and I debriefed. Others have been sending us questions as they’re problem-solving around what’s working and what’s not.

“I think they’re taking the right approach, cautiously entering into this knowing things are probably going to go wrong and then figuring out how to fix them,” Paige said.

As civil and environmental engineer Pedro Alvarez noted, “Teaching via Zoom is easy, but it takes longer to drive home points and answer questions.”

Fortunately, faculty seem willing and eager to share among themselves what they’re learning about online resources.

Some of those resources are available through a webpage assembled by Associate Dean of Natural Sciences Ken Whitmire, mathematician Stephen Wang and chemist Kristi Kincaid, both lecturers, and their colleagues. They include links to resources for working remotely, Zoom and Kaptivo tutorials, advice on giving students written feedback and online grading with Gradescope.

“I had started working on an informational sheet for my students, but I saw Stephen’s, and it was pretty great already,” Kincaid said. “So I took his text, added the screenshots I had taken for my sheet, and then changed the instructions where it differed for my CHEM students versus his MATH students. Once I had my document, I sent it to Ken, thinking that others might find it useful.

“I found the amount of helpful resources that were sent/offered to me to be overwhelming,” she wrote. “So the dean’s office curating a small list for faculty and faculty curating a small list for their students seems like a good way to wade through it all.”

Kincaid offered special praise for Rice’s Office of Information Technology. “Rice OIT has done a phenomenal job in helping us through all this, so I can’t let the opportunity for a public thank you to go by without taking it,” she said.

Biogeochemist Caroline Masiello said her students have stepped up to the online challenge. “They seem to be quite resilient in how they’re adapting to the situation,” she said. “They have been remarkably patient as we faculty have learned to use Zoom, talking us through some of the features in real time.

“I had to rework my field-trips-only class,” Masiello said. “We got some good trips in before the break, but will miss more than half of them. Instead, now, the students are going to do online video interviews with alumni and local professionals working in Earth and environmental sciences.”

Mechanical engineer Laura Schaefer missed seeing her students in person, “but I know that they have it much worse than we do.”

“I also miss the exercise of bounding back and forth in front of the class, gesturing emphatically,” she said. “Thank goodness I have a dog I can walk to get rid of some of that excess energy!”

Like many, Schafer is prerecording her lectures but holding office hours online. “For the lectures, I’ve had great turnout, especially considering how scattered our students are now around the world,” she said. “One nice and unexpected outcome is that some students who don’t tend to raise their hands in class are more likely to participate.”

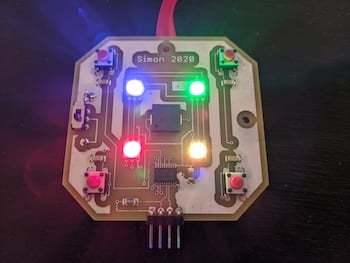

Electrical and computer engineer Caleb Kemere’s solution went beyond virtual. He sent students in his Digital Systems Laboratory the 1970’s electronic memory game Simon along with tools to make custom modifications to the units.

“The only thing I did was refuse the invitation to switch the class from a ‘we-make-things’ lab to something based on a simulator. They need and want the hands-on experience,” Kemere said. (Read Patrick Kurp’s story about the project here.)

Chemical and biomolecular engineer Haotian Wang believes the future is presenting itself, in a way, disguised as crisis management. “It opens up new trends of research communication,” he said. “I believe there will be many conferences in the future held online, instead of traveling to a destination.”

Christopher Fagundes, a psychological scientist whose studies of stress on human health have particular relevance now, said that with no current classes, teaching isn’t a problem for him this semester. “However, I do have a large lab,” he said. “Every morning, I meet with my team over Zoom. We discuss what we are trying to accomplish for the day. I’m also using this time to foster social support and encourage everyone to create and maintain a routine.”

“The message we were really clear about was to just focus on learning objectives for the course and think about how to do that as low-tech as possible, because that's going to create the least amount of obstacles,” Paige said.

Bioengineer Jane Grande-Allen certainly took that to heart.

“I’ve been forcing myself to take the technology approach, and I switched to using a tablet,” Grande-Allen said of her strategy to distribute documents to her students. “(Microsoft) OneNote is good for this, where I can just write on the app with an Apple Pencil. It captures my notes, and I use Zoom to record myself writing them and save that for students.

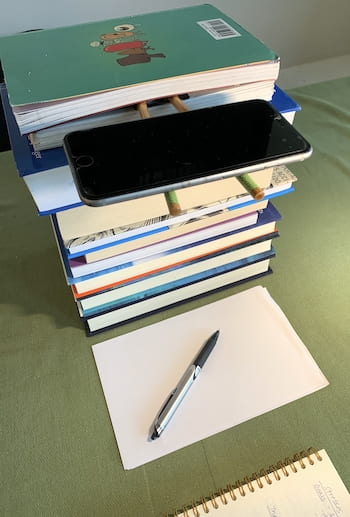

“But because I couldn’t figure out how to record from the document camera, I made my own,” she said. “I put a stack of books really high and I duct taped chopsticks to the top book. Then I put my iPhone on the chopsticks. That works.”

Paige had three best-practice recommendations: maintain consistent communications with students, make sure they “show up” by making lessons as easily accessible as possible, and maintain structure.

“That’s really important,” she said. “There's going to be a wide variety of responsibilities and things that are pulling their attention while they're at home. It may be Netflix, it may be caring for younger siblings, and it may be parents who, all of a sudden, are unemployed.

“It’s good to provide structure that’s still flexible enough for all students to engage no matter what,” she said.