Every single edition of the Campanile, Rice’s yearbook, is now digitized and available online.

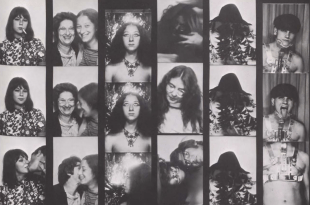

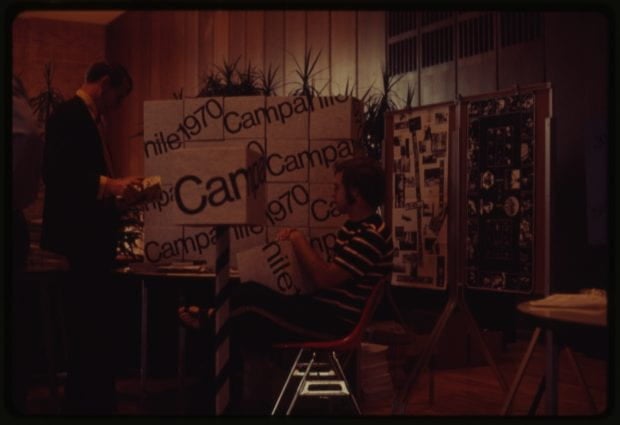

That includes the special two-volume year in 1944 during World War II and the 1970 yearbook that was not a bound volume at all — just a cardboard box filled with assorted materials including Monty Python-inspired illustrations, atmospheric photos of student protests inside Allen Center and a 45 rpm record.

“It is kind of like a time capsule,” said Amanda Focke, head of special collections at the Woodson Research Center in Fondren Library. “It is one of the most popular yearbooks that people want to see in person when they come in to the library.”

Thanks to the ambitious undertaking by the Woodson staff, you can now examine its contents virtually — good news at a time when the entire world is social distancing and Fondren Library remains closed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

For years, universities across the nation elected not to digitize their yearbooks, citing privacy issues. Rice had a policy of waiting at least 75 years to publish its Campaniles online out of concern for its students’ privacy.

“Those yearbooks from way back when were created at a time when nobody would ever have an expectation that those things would be going online,” Focke said. “That was a standard in the field.”

But times change, and soon a new standard arose: transparency.

Rice had always had two volumes of each year’s Campanile in its archive for anyone who wanted to see them, but the trend toward transparency spurred Focke to offer even greater access to the yearbooks by digitizing them.

By October 2019, almost every issue was fully digitized, a process which includes the painstaking creation of metadata and addition of tags, bookmarks and alternative text for photos — important detail work that ensures each yearbook also adheres to accessibility standards.

These steps are increasingly required for new web content, in order to ensure its accessibility to people with a diverse range of hearing, movement, sight and cognitive abilities. But Focke said these provisions are important regardless of whether or not they’re mandated.

“For these yearbooks and all the other things that we in the archives put online, we try to make them high-quality digital objects that can be useful to the widest number of people,” she said.

All they were missing for a full Campanile collection were two issues: 1936 and 2017, both of which were still in various steps of digitization. Luckily, it was work Focke and her staff could do from home — rewarding work, but also fun work.

“What's interesting about the yearbook over time, having just spent time looking at them over the decades, is that they change so much,” Focke said. “And because it's a student publication, it's always an expression of the students there at that time and what’s important to them.”

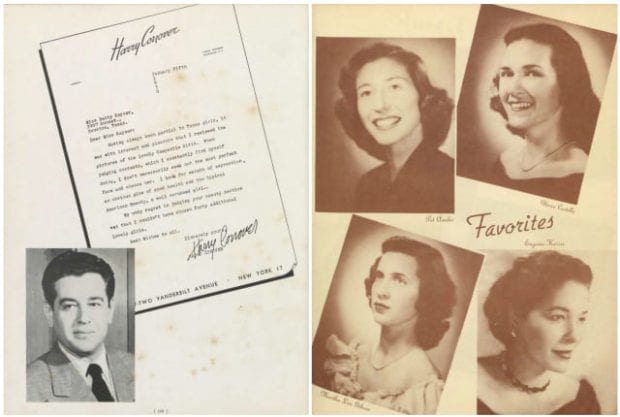

Women’s literary societies were crucial in the years before women could live on campus at Rice, providing much-needed social structure.

“And then you kind of don't really see them as much anymore because college life just takes over,” Focke said.

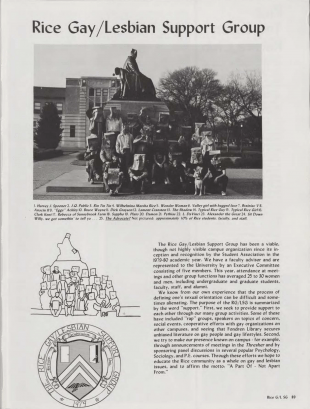

“You can also see the development of the LGBTQ presence on campus, starting off invisible and then making its way to, ‘OK, now we're in the yearbook as a club, but we're in here with people's faces covered and made-up names.’”

From the 1920s on into the 1950s, she said, no yearbook was complete without a “Vanity Fair” section that spotlighted the school’s more glamorous students. Campaniles weren’t organized by college until the 1960s. And by the 1970s, the yearbook had been so thoroughly deconstructed that it was, well, a bunch of stuff in a box.

The 2020 Campanile is still under construction, though there are still plans for it to be a physical book, according to director of student media Kelley Callaway.

It too, however, will one day be scanned and uploaded into the university’s digital archives at scholarship.rice.edu — a time capsule of life at Rice before, during and immediately after a global pandemic.