Challenging. Supportive. Defining. Ever-changing. Apathetic. Surprising.

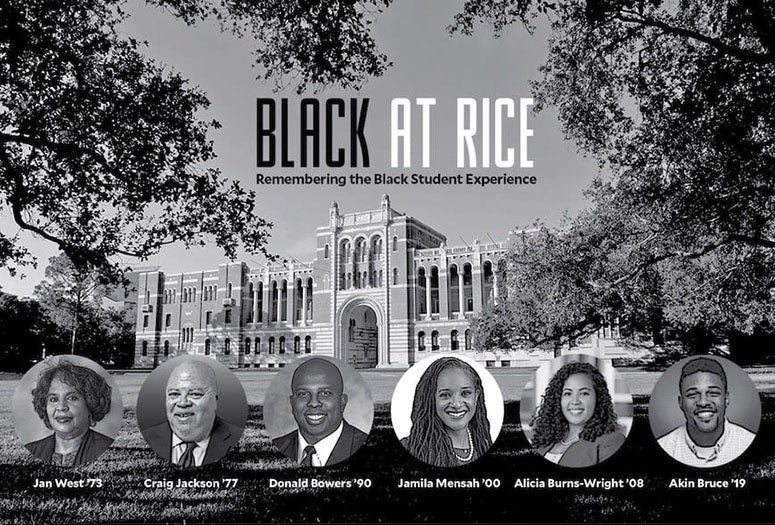

These were a few of the words chosen by Black alumni at Rice to sum up their time at the university during “Black at Rice: Remembering the Black Student Experience,” an Oct. 7 panel convened via Zoom and sponsored by Rice’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice.

“When it comes down to questions about how we can improve Rice and how we can make Rice a more diverse and inclusive place — which is what we all want and which was originally what the charge of the Task Force was all about — taking that time to really share in those experiences and listen to those experiences is something that’s really necessary,” said moderator Summar McGee ’00.

McGee asked fellow alums who ranged from the Class of 1973 to Class of 2019, one per decade since Rice first admitted Black students in 1965, to prepare three words that described their undergraduate years. As with the 90-minute discussion, the answers were wide-ranging and varied.

Jan West ’73, Rice’s assistant director of multicultural community relations in the Office of Public Affairs, recalled a Rice that did not yet have a Black Student Association (BSA) — she and her peers would eventually start the university’s first Black student union — but was still considered a “radical” campus when she matriculated in 1969 thanks to a series of protests that included a teach-in that February and the student occupation of Allen Center in 1970.

As a freshman, West was the only Black student in Brown College and often the only Black student in her classes. And although she’d come from a segregated school herself, where she had been surrounded by Black classmates, she was undaunted by the dramatic change in demographics.

“I was one of the children that watched other children being tortured by guard dogs and the whole Birmingham bombing and I saw the schools integrated and it was awful and scary, but I was so determined to leave Port Arthur, Texas, and try something bigger and the larger world that was I coming to Rice, no matter what,” West said.

“And I was so pleased to see people show up to move me in,” much as students still do during O-Week, West said. She became fast friends with her Brown College roommates and found professors who cared for and defended her amid difficult classroom situations.

“Was it a perfect situation? No,” she said. “But I saw Rice as a supportive place.”

Craig Jackson ’77, professor of law at the Texas Southern University Thurgood Marshall School of Law, also came to Rice at a time when his previous schools had all been segregated. Jackson found the racial climate at Rice “troubling” by the time he matriculated in 1973.

“I was always in the majority before I came to Rice and all of a sudden at Rice I'm a minority and I am a guest,” Jackson said. “I didn't see into the logic behind that so I rejected that notion of being a guest.”

It was an atmosphere, he said, that was challenging yet apathetic.

By the time Donald Bowers ’90 came to Rice, he found a racial climate he described as “in transition.” Bowers is now the vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas in Houston and a member of the Rice Board of Trustees. But as one of only 30 Black students in his class, Bowers recalled, he found himself becoming closed-off and withdrawn.

“People who know me would say I'm gregarious and I'm outgoing, but if you were around me at Rice and you weren’t one of those people who I relied on or who I had an association with, I did not have much to say to you because I didn't know who you were, what you may have had as a motive or how you may have thought of me — and so I did not engage.”

Code-switching, Bowers said, was very much a reality for him and his fellow Black undergraduates, many of whom were also his fellow student-athletes and became his closest friends.

“It was definitely an environment where, when I was with those people who were within my circle, I could be me,” Bowers said. “When I was in the rest of Rice, I felt like I had to keep my guard up.”

In 1996, when Jamila Mensah ’00 matriculated, she was lucky to have a built-in support network thanks to her brother and his fellow Rice football teammates. But Mensah, “very much a joiner,” quickly expanded her circle.

“I tried to do everything that the track schedule allowed me to do,” said Mensah, who worked for the library, volunteered in the admissions office and served as an O-Week adviser. “Rice really allowed me to do that. I felt like I could be whatever I wanted to be in that space.”

Growing up, like Bowers, in heavily integrated school systems prior to coming to Rice, Mensah said she didn’t remember any open hostility on campus.

“Or to the extent that I did experience that, it wasn't any different from what I experienced growing up in … the suburbs in Houston,” said Mensah, who is now a partner at the Houston offices of Norton Rose Fulbright working in employment and labor litigation.

Washington, D.C. attorney Alicia Burns-Wright '08 visited Rice during Vision Weekend, sponsored by the Office of Admissions to recruit underrepresented minorities. Coming from a “very diverse” high school in Las Vegas, Burns-Wright saw a Rice campus during that overnight stay that was filled with prospective students of color.

“I had a great time at Vision but was a little shocked when I got to campus as a freshman, because that diversity was very scattered relative to everyone else,” she said. “That being said, I did as Jamila advised and I found my tribe.”

Burns-Wright got involved in BSA and became “very at home” in the sociology department, where her professors cheered her on whenever she struggled.

“I felt very supported by a lot of the faculty — not all the faculty at the time — and I felt very supported over the years by President Leebron,” she said.

Still, there were times when she felt the university failed to live up to its ideals, particularly two incidents she remembered from her sophomore year. In one, Burns-Wright said the Rice Thresher “ran a very racist Backpage,” the content of which the provost at the time defended.

The second memory was of a Sid Richardson College “40s Party” held on Martin Luther King Jr. Day that had been banned in 2004 due to its offensive racial connotations, yet continued on as an unregistered event. The 2008 iteration of the party resulted in a racist message scrawled on the door of the Sid Richardson college coordinator as well as other incidents of vandalism.

“Aside from that I loved Rice,” said Burns-Wright, who remains active in the alumni community. “Obviously I'm very invested in Rice — I volunteer a lot and I'm happy to give back — and I'm so proud of how far Rice seems to have come.”

Akin Bruce ’19, the most recent graduate on the panel, said he was pleasantly surprised to find a diversity of backgrounds within the Black community at Rice.

“At Rice we have a very strong African student and Caribbean student population,” said Bruce, who served as Lovett College president, O-Week coordinator and a campus tour guide, among other roles.

He never encountered “direct malice” from his peers, he said, but still faced situations in which he saw fellow Black students treated differently by campus police and other Rice figures.

“You don't go here just because you're a Black person” was a common assumption made in these situations, Bruce said.

Adding to this, he said, was the fact that despite an increase in overall enrollment rates for Black students at Rice, the division of the student body into 11 residential colleges can lead to feelings of isolation, as Black students still represent less than 10% of the undergraduate population.

“While I was on campus, there were other members of the Black community that felt more isolated than I did or like felt like their voices weren't being heard like I thought mine was being heard,” Bruce said. “And I felt like that had a lot to do with … being broken up into 11 different communities.”

After sharing their memories of Rice, the members of the panel took questions. Several of the questions centered on current discussion about whether or not to remove the statue of founder William Marsh Rice due to his ownership of slaves. This question is currently one of many being contemplated by Rice’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice, though the decision on the matter rests with the Board of Trustees.

“As a member of the Task Force, I want to reserve an opinion on the statue itself,” Bowers said. “But I will say this, I think what we've learned, even through this call this evening, is how each generation rises and reaches more towards its ideal at the kind of institution that Rice supposed to be.”

West said Rice has become a place she never could have imagined in 1969.

“You have something that we dreamed of: the African and African American studies center,” she said. “So, use it. There are some things I didn't understand about my cultural background till I took a Black history course at Rice my senior year.”

Bowers joined her call for continuing education around these topics and more.

“The Task Force is putting together lots of great forums and opportunities for people to increase their knowledge and understanding,” Bowers said. “I think every student, every alum, anybody who really has Rice in their heart should be connected to this and be a part of this learning process.”