Rice University leads research to find the best nanofluid for heat transfer

A mixture of diamond nanoparticles and mineral oil easily outperforms other types of fluid created for heat-transfer applications, according to new research by Rice University.

Rice scientists mixed very low concentrations of diamond particles (about 6 nanometers in diameter) with mineral oil to test the nanofluid’s thermal conductivity and how temperature would affect its viscosity. They found it to be much better than nanofluids that contain higher amounts of oxide, nitride or carbide ceramics, metals, semiconductors, carbon nanotubes and other composite materials.

The Rice results appeared this week in the American Chemical Society journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

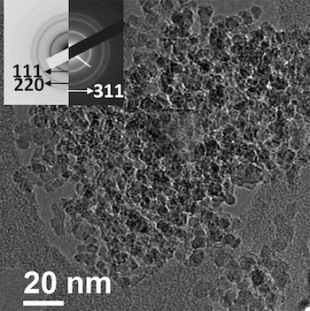

Mineral oil combined with nanodiamonds is more effective than other nanofluids for heat-transfer applications, according to researchers at Rice University. The researchers tested nanodiamonds in mineral oil at concentrations up to 0.1 percent weight to see how well it would transfer heat while remaining at a usable viscosity. Courtesy of the Ajayan Group

The work that could improve applications where control of heat is paramount was led by Pulickel Ajayan, chair of Rice’s new Materials Science and NanoEngineering Department, and Rice alumnus Jaime Taha-Tijerina, now a research scientist at Viakable Technology and Research Center in Monterrey, Mexico, and a research collaborator at Carbon Sponge Solutions in Houston.

Thermal fluids are used to alleviate wear on components and tools and for machining operations like stamping and drilling, medical therapy and diagnosis, biopharmaceuticals, air conditioning, fuel cells, power transmission systems, solar cells, micro- and nanoelectronic mechanical systems and cooling systems for everything from engines to nuclear reactors.

Fluids for each application have to balance an ability to flow with thermal transport properties. Thin fluids like water and ethylene glycol flow easily but don’t conduct heat well, while traditional heat-transfer fluids can be affected by stability, viscosity, surface charge, layering, agglomeration and other factors that limit essential flow.

Researchers have been looking since the late 1990s for efficient, customizable nanofluids that offer a middle ground. They use sub-100 nanometer particles in low-enough concentrations that they don’t limit flow but still make efficient use of their heat-transfer and storage properties.

Nanodiamonds are proving to be the best additive yet. They carry most of the properties that make bulk diamond so outstanding for heat-transfer applications at the macro scale. Single diamond crystals can be 100 times better at thermal conductivity than copper while still acting as an efficient lubricant.

An electron microscope image shows diamond nanoparticles suspended in oil. The inset shows the diffraction planes of the particles. Courtesy of the Ajayan Group

“The great properties of nanodiamond — lubricity, high thermal conductivity and electrical resistivity and stability, among others — are quite impressive,” said Taha-Tijerina. “We found we could combine very small amounts with conventional fluids and get extraordinary thermal transport without significant problems in viscosity.”

In tests, the researchers dispersed nanodiamonds in mineral oil and found that a very small concentration — one-tenth of a percent by weight – raised the thermal conductivity of the oil by 70 percent at 373 kelvins (about 211 degrees Fahrenheit). The same concentration of nanodiamond at a lower temperature still raised the conductivity, but to lesser effect (about 40 percent at 323 K).

They suggested a mechanism somewhat like percolation – but perhaps unlike anything else yet seen — takes hold as oil and diamond molecules collide when heated.

“Brownian motion and nanoparticle/fluid interactions play an important role,” Taha-Tijerina said. “We observed enhancement in thermal conductivity with incremental changes in temperature and the amount of nanodiamonds used. The temperature-dependent variations told us the changes were due not just to the percolation mechanism but also to Brownian motion.”

Co-authors are former Rice postdoctoral researcher Tharangattu Narayanan, now at the CSIR-Central Electrochemical Research Institute, Karaikundi, India; Chandra Sekhar Tiwary, who has a research appointment at Rice and is a scientist at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India; and Rice alumna Karen Lozano, a professor of mechanical engineering, and Mircea Chipara, an assistant professor of physics and geology, both of the University of Texas Pan American, Edinburg, Texas. Ajayan is Rice’s Benjamin M. and Mary Greenwood Anderson Professor in Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science and of chemistry.

Mexico’s National Council for Science and Technology and the Army Research Office through the Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative supported the research.

Leave a Reply