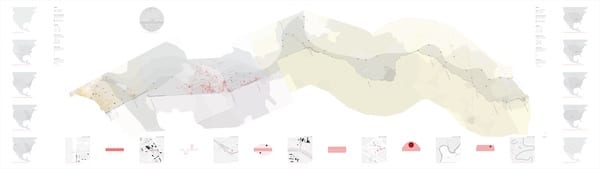

An illustration from architecture student Veronica Gomez’ thesis presentation, “Claiming the Line.” Click on the images for a larger view. Rendering by Veronica Gomez

Architecture student’s thesis takes compassionate look at US-Mexico border’s human element

Veronica Gomez understands the debate over the proposed wall between the U.S. and Mexico, but doesn’t believe the debaters fully understand what life is like for those who live and work in proximity to the border.

Veronica Gomez

The newly minted Rice Architecture alumna took a deep look at dynamics along the border, not only for how it keeps people apart but also as a place that brings them together, even if only for a few precious minutes.

“We understand it in a very abstract way, perhaps through what we hear in the news,” Gomez said. “For me, it was more interesting to look at people.”

Gomez based her graduate design thesis on a yearlong study of the border’s history and how people in its neighborhoods relate to it and to each other, and presented it in an unusual manner: as a fold-out, 14-foot-long, stitched canvas map that let her easily expand and compress aspects of her findings during her presentation. That choice, she said, aligns with her choice of adviser, Dawn Finley, a Rice associate professor, director of graduate studies and an architect with a particular interest in fabrics.

Gomez was one of 20 graduate students to present a thesis to a panel of judges, all prominent figures in the field of architecture, in January. The presentation is the students’ final requirement to earn a Master of Architecture degree. Projects included such subjects as shared storage in the 21st century, models for Arctic development and strategies for high-speed rail in urban settings, each a thorough analysis of theoretical concepts in architecture and how they might be applied to solve real-world problems. (See examples of past thesis projects here.)

The project by Gomez, who came to the U.S. from Mexico as a child, had a relevance she didn’t anticipate when she started down the path last year.

“I did not want to focus on border security, although I investigated it as part of the different systems that connect to the region,” she said. “To me, the border represents more of a region rather than a division between two countries.”

Her presentation encompassed the border’s past as well as its present influence on life and death on both sides, all represented on the massive map that laid out not only major infrastructure but also had examples of the interactions that happen daily. Along the left and right of the map are continental segments that show how the border has evolved over time, while along the bottom are illustrations that detail ongoing transactions.

Among them are the location and layout of a refugee detention camp for children in Tornillo, Texas; a U.S.-side farm that lies awkwardly between the border fence and the actual border; and detailed illustrations of the San Diego-Tijuana and El Paso-Juarez crossings.

“Those talk about specific places and specific moments,” Gomez said, giving an example. “I have one that maps the route of a girl who goes to school every day and has to cross the border (from Juarez to El Paso). That’s what’s interesting to me: the people who interact with this place every single day.”

The large-scale map is unfolded for Gomez’ presentation.

Thousands of Mexicans duplicate the girl’s arduous journey every day as they cross to work or shop and encounter a barrier that complicates the process. In at least one place — Friendship Park in San Diego — Gomez said simply communicating across the border in the way for which the park was designed has become difficult, if not impossible. At the park, people can meet through a fence for up to 30 minutes during limited weekend hours.

“The park is supposed to represent friendship between the two countries,” she said. “People who cannot cross legally to the other side used to meet in this place. But now, there’s a second fence which inhibits people from touching the first fence. For me, that was shocking, but there are a lot of these little instances I was interested in.

“I saw video of another place in El Paso where people were given shirts of different colors and allowed to meet for five minutes or so,” Gomez said. “There were people crying and emotional because they hadn’t seen each other or touched each other for many years.”

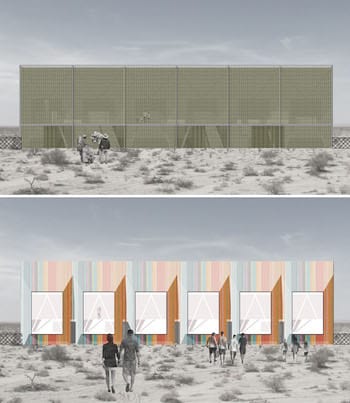

That situation, she feels, requires a more humane solution. To that end, Gomez proposed and designed a building she would put along the border at San Luis, Arizona, and San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico, as a place where family and friends can meet without crossing, but also without the onerous structures that now stand in their way.

Another purpose of the building would be “to collect stories from people who interact or have a relationship to the border, to give them a voice,” she said. Visitors would be encouraged to contribute oral histories through audio recordings and written transcripts, which would be catalogued and made available. With a colorful, fabric-dominated façade on the U.S. side and a plain one facing Mexico, the design “embodies the dual character of the border” and emphasizes its unbalanced nature, Gomez said.

Gomez’ design for a data collection center at the border would facilitate meetings and host a collection of oral and written histories of visitors. The building also makes a point about disparity, as the Mexican side (top) presents a plain face, while the U.S. side is more colorful. (Renderings by Veronica Gomez)

Further highlighting the tension, she noted U.S. visitors would walk into the building at ground level, while Mexican visitors would access the interior by walking underneath to connect with the other side.

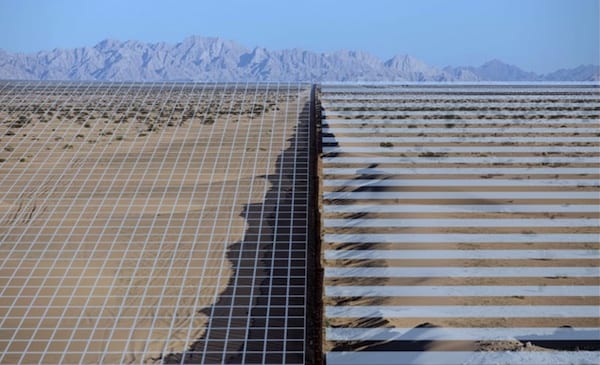

Gomez noted that whether or not a wall extends all the way along the border, crossings remain essential to the economies of both nations, from trade regulated by the North American Free Trade Agreement (or its negotiated successor) to workers who live in Mexicali, Mexico, but cross the border to harvest crops in California’s Imperial Valley. She noted many people who work in San Diego choose to live across the border in Tijuana for its more affordable housing, and cross every day.

“People will talk about … wanting a fence or even a wall,” Gomez said. “I don’t think you can propose those things without fully understanding the region. People don’t really see that human component. They have a tendency to generalize people as well: ‘Oh, those people are bad, or immigrants are not good for the country.’ Which is totally erroneous.

“There is a kind of connection between the countries that the U.S. only has with Mexico and Mexico only with the U.S.,” she said. “It’s very unique. I think preserving the good things is more important than just creating a barrier between the two countries, because both benefit from each other.”