By Greg Marshall

They fought Nazis and fascism, fought segregation and racism and have lived to see a black U.S. commander in chief; but were it not for their base commander, Rice alumnus Col. Noel Parrish ‘28, the Tuskegee Airmen might never have had taken to the skies. On Feb. 15, nearly a dozen of the original Tuskegee Airmen returned to the place where it all started, Moton Field in Tuskegee, Ala., to dedicate the newly renovated national historic site, greet surviving comrades in arms and reflect on those who supported their double victory: over the enemy in World War II and over the prejudice they fought in the country they swore to defend.

“The Tuskegee experiment was an experiment that was meant to fail,” said retired Brig. Gen. Leon Johnson, national president of the Tuskegee Airmen Inc., the organization dedicated to preserving the history of the pioneering black flight crews, ground crews and support personnel who trained at Moton Field and nearby Tuskegee Army Air Field between 1941 and 1946. “The prevailing belief in the military at the time was that blacks lacked the mental faculties to learn to fly, service and support combat aircraft, so initially, even here, they were treated as second-class citizens and subjected to some very unfair practices. When Noel Parrish took over as commander, he abolished those practices. He is regarded as someone who allowed the experiment to succeed based on its own merit and not fail because of outside pressures.”

Noel Parrish

The idea of succeeding on merit is one that Parrish must have absorbed early in life. Born in Kentucky and raised in Georgia and Alabama, he graduated from high school at the age of 15, and in 1928, at age 18, he earned a bachelor’s degree in history from the Rice Institute. After his first year of graduate school, he left Rice and decided to hitchhike to California, but finding jobs scarce in the summer of 1930, he enlisted in the Army as a member of the 11th Cavalry. In the summer of 1931, Parrish was appointed a flying cadet, and he earned his wings in 1932. For the next nine years he rose through the ranks, and in March 1941, while still a student at the Air Command and Staff School at Maxwell Field in Alabama, he was appointed assistant director of training for the Eastern Flying Training Command. This brought him into direct contact with the Army’s first ever all-black flying unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron, formed that same month.

Parrish must have been impressed with what he saw in that first class of young African-American cadets whom he helped to train, because upon his graduation from command school that summer, he elected to forgo the opportunity for a combat command of his own and instead, two days before Pearl Harbor, on Dec. 5, 1941, he became the director of training at the Tuskegee Army Flying School. A year later, in Dec. 1942, he was promoted to base commander.

“Prior to his becoming commander, segregation was still a part of Tuskegee Army Air Field,” said Tuskegee Airman Lt. George Hardy, who earned his wings under Parrish in 1944. “Col. Parrish changed that once he took over. He made it much easier for blacks on the base.”

Col. Roosevelt Lewis, president of the Tuskegee Chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen Inc., concurred: “[He] gave them the respect that was not the norm at that time. The Airmen speak in glowing terms about Noel Parrish — some will tear up — because he gave them the opportunity to prove themselves in the aviation program. They loved him because he permitted them to succeed.”

“He was a fair man,” said Calvin Moret, who came to Tuskegee as an 18-year-old cadet and graduated in 1944 as a flight officer. “Col. Parrish had a hand in picking the instructor pilots, and they never put me in a position to be looked down upon or made to feel inferior. They knew we were training to go over and fight for our country, so they did the best they could to give us the instruction to do the job at hand.”

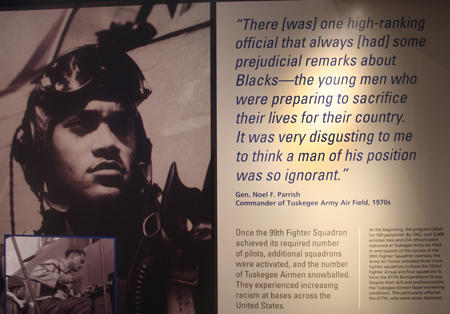

But learning the job was only part of the battle. Being allowed to apply their training in actual combat was yet another hurdle. “They had to fight just to get into the fight,” Johnson said. That reality is reflected in the exhibit at the Moton Field National Historic Site, where a large wall features a quote from Parrish:

“There [was] one high-ranking official that always [had] some prejudicial remarks about Blacks –the young men who were preparing to sacrifice their lives for their country. It was very disgusting to me to think a man of his position was so ignorant.”

Lewis of the Tuskegee Chapter remembered hearing from a legendary Airman of the effect this had on Parrish at the time: “[Col. Parrish] would have to leave Tuskegee from time to time to go to Washington to report. Lee Archer, who would become one of the Airman with the most kills in the war, flew him to Washington for these meetings. Lee said that Col. Parrish would be upbeat on the way there, but beaten up on the way back.” According to Lewis, it was clear to Archer that Parrish was pressing his own superiors to give the Tuskegee Airmen a legitimate combat role. “Lee said, ‘I loved the man for what he did,’” Lewis said.

Eventually, their commander’s persistence paid off, and the Tuskegee Airmen did get the chance to fight, flying more than 1,500 combat missions in North Africa and Italy, shooting down more than 100 aircraft and disabling another 150 on the ground; they received three distinguished unit citations.

Eventually, their commander’s persistence paid off, and the Tuskegee Airmen did get the chance to fight, flying more than 1,500 combat missions in North Africa and Italy, shooting down more than 100 aircraft and disabling another 150 on the ground; they received three distinguished unit citations.

“We proved that we could handle it, and that led to integration of the services,” Hardy said. “In 1947, when the Air Force became a separate branch of service, they realized these guys could fly as well as anybody else, the mechanics could repair airplanes as well as anybody else and the other guys [supporting] the group or squadron could do their jobs as well as anybody else, and so the Air Force announced, in April of 1948, that it was going to integrate racially. Three months later, President Truman signed his executive order telling the Army, Navy and Air Force to submit their plans for racial integration.”

“When that happened, the U.S. military became the largest integrated institution in the country,” Johnson said. “All that was started by a Rice graduate named Noel Parrish.”

After World War II, Parrish continued to advance both in the U.S. military and academically, eventually earning the rank of brigadier general, and returning to Rice after his retirement in 1964 to earn master’s and doctorate degrees in history. He died in 1987.

Today, at Moton Field’s newly renovated Hangar Two museum, Parrish himself is a part of history, as are the pioneering black aviators, ground crews and support personnel who served under his command. In the new exhibit, a photo of Parrish is displayed prominently under the heading “Honor Roll” along with such legendary Tuskegee Airmen as Gen. Daniel “Chappie” James Sr., Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. and C. Alfred “Chief” Anderson. In the exhibit, the accompanying information credits Parrish for his efforts to combat racial prejudice in the U.S. military both during and after the war.

But perhaps the greatest evidence of the respect and affection with which Parrish is regarded by the men and women he led may be seen at the Tuskegee Airmen’s annual convention when the highest award for service to the organization is presented, an award named in honor of the man who confronted racial prejudice within his own chain of command to help the Tuskegee Airmen earn their wings: Rice graduate Brig. Gen. Noel Parrish.

— Greg Marshall is director of university relations in the Office of Public Affairs.

What a remarkable story/article! To all involved-an excellent job done, one that is most appropiate and encouraging. Thanks for the history facts. I was moved and touched by it very much.

A wonderful story indeed. I remember General Parrish from my undergrad years at Rice. If memory serves he was a resident fellow at Weiss college or at least took most of his meals in the Weiss Commons and made it a point to strike up acquaintances among the undergrads over lunch or supper. I remember him as a kind and gentle man and a very interesting conversationalist, especially on matters relating to his studies in history, but I then knew nothing of his past life and his remarkable past contributions in the Air Corps/Air Force. Thanks for filling in the gap.