BY RILEY HATCH

During my education, I have read about Earth’s amazing tropical rainforests and phenomenal barrier reefs — great hubs of life that have served as living laboratories for biologists for more than a century. This summer I experienced these great centers of biodiversity in person, and I discovered that some of nature’s lessons cannot be learned from books.

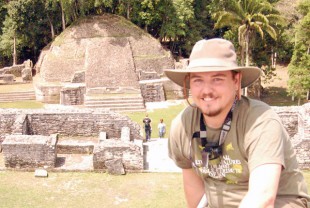

Through Rice's Tropical Field Biology course, visiting student Riley Hatch was one of 12 students who experienced one of Earth's great centers of biodiversity and discovered some of nature's lessons cannot be learned from books.

I was one of a dozen students enrolled in Rice’s Tropical Field Biology (EBIO 319) course, which took place over 15 days in Belize. We lucky 12 and our fearless leaders, Rice faculty members Scott Solomon (lecturer in ecology and evolutionary biology) and Andre Droxler (professor of Earth science) and Rice graduate student Nick Rasmussen, saw for ourselves what these huge and powerful ecosystems contained.

Belize’s barrier reef was an underwater wonderland that seemed to be composed of many chaotic mounds of living stone surrounded by a rich variety of fish, echinoderms and the occasional mammal or reptile. When we prepared to leave the reef, we saw past the chaos into the incredible sense and order of the reef ecosystem, including its natural and geological history, and the fascinating interactions between the organisms of the reef.

All of this clarity was accomplished through seeing firsthand the organisms we studied and through conversations in the field. In the evenings, we delved more deeply into the details of the ecosystems as we shared lectures on topics related to the ecosystem we inhabited during our time in Belize. We broke into groups to study specific organisms, and each group shared its knowledge as we prepared blog entries about the sightings and actions of our respective study groups.

We learned about the scourge of the invasive Lionfish, genus Pterois, by seeing it in person and discussing the problem with a scientist at the Smithsonian research facility at nearby Carrie Bowe Cay. We learned about the white band disease of the coral genus Acropora and the victorious return of Acropora palmata by seeing these incredible animals so close that we could reach out and touch them. This is where Dr. Solomon and I developed the mantra of the course: “You can’t learn that in a book.”

As we waved goodbye to the enchanted mangrove island we had called our home during six days on the reef, we prepared to enter the treacherous but beautiful tropical rainforest of Belize. The experience awaiting us at our remote inland research facility was so similar to that of the reef that our slogan for the course did not change. In the forest, the cycle repeated. Our initial wide-eyed awe quickly melted away to a confident mastery of the forest.

By the end of our time at the research station, we had the privilege of observing the annual mating flight of the leafcutter ant Atta cephalotes. We captured snapshots of cougars, ocelots and other mammals in camera traps set throughout the forest. We conducted experiments regarding predation and the limited resources in forests. We spent our mornings observing tropical birds that most of the world only ever sees in nature magazines.

Since my return to Houston, folks have asked me to name the three main things I took away from the course. If I must choose only three, I would say: I have gained a realization of the dynamic nature of the forest and the reef and an appreciation for the fragility of the ecosystems. I brought home a respect and admiration for the symbiotic relationship between the plants and animals of the forest, particularly when referring to the ants. Lastly, I took away a sense of awe at the power of organisms to find a niche where there is none, as exemplified by the amazing mangrove tree islands we visited on the reef.

By spending time fully immersed in the forest, we learned to speak its language and to understand the sounds, smells and sights beneath the canopy. Thousands of books have been written about the tropics, and reading them is a perfectly valuable experience. However, in order to truly understand the tropics, I recommend only this: Go see it for yourself.

EBIO 319 is scheduled again for summer 2013. The blog entries of all 12 students who took the course this summer can be found at www.owlplayground.com/2012EBio319/.

Riley Hatch is a senior-level student of biology and chemistry at the University of Houston.

See Dr. Solomon talk about this project here

You can see a video report relates to this in course in the EdTech video Archives