An art history class tours a two-story piece of university history

In Sam Houston Park, a two-story Greek Revival home holds its own amid the skyscrapers of downtown Houston. The mid-19th-century building has been painted yellow; ionic columns dominate the front, and large windows peer out from all sides.

Joseph Manca’s HART 360, an art history class, took a field trip to the house Wednesday. They paced across its squeaky wooden floors, climbed its narrow staircase and sketched the furnishings in its parlor.

Joseph Manca, left, shows his class the exterior details of this mid-19th century Greek Revival home.

It was the perfect subject for Manca’s class to study; the course is devoted to American architecture and decorative arts before 1900, and this home offered good examples of both. But there’s another factor that always makes this a must-visit house for Manca’s classes: It was once the home of the university’s founder, William Marsh Rice.

The Nichols-Rice Cherry House was built about 1850 in Houston’s courthouse square by Ebenezer Nichols, Rice’s friend and business partner. Nichols and Rice both arrived in Texas in 1838, and the men went into business and made their fortunes together.

When Nichols’ business ventures took him to Galveston, he sold the house to Rice in 1856, and Rice and his first wife lived there until she died in 1863.

After that, Rice left Houston. For the rest of his life – even after he remarried – Rice lived in New York and came to Houston only when business required it.

Rice rented out the large home, then sold it to a real estate company in 1873. It was moved to another location and modified; it changed hands a couple of times. Finally, the artist Emma Richardson Cherry bought the house in the 1890s and moved it to the city’s developing Montrose area. Cherry lived in the house until she died in 1954; then Houston’s Heritage Society acquired the structure and moved it one more time to its current location in Sam Houston Park.

Now the home, called the Nichols-Rice-Cherry House, is a museum, and the Heritage Society offers tours of the home to visitors and student groups.

“This house, as you can see, is a great example of Greek Revival,” Manca told his students on the home’s front porch. He pointed out its columns, its capitals, the intricate honeysuckle anthemia carved above the door.

Inside, collections curator Wallace Saage took over the tour and told students about the home’s furnishings and décor. They’re not original, but they are typical of the time period, Saage said – mirrors, rosewood chairs and a classical settee with paw feet were just the sort of furnishings a wealthy couple would have chosen in the 1850s.

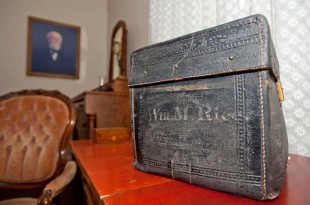

There’s just one item in the house that actually belonged to the Rices, Saage said. In a room just off an upstairs bedroom, he showed the group a worn leather letter box bears the monogram “Wm. M. Rice.”

Rice would have used the box much like a briefcase, Saage said. “He would have brought it home, carried his papers in it.” Today it’s the only Rice possession the Heritage Society can locate.

The Rices were frequent entertainers, Saage told the class; they often invited Sam Houston to visit, and they opened up the home’s entire first floor every year for a legendary holiday party. The big windows can transform into doors that allowed residents and their guests to walk out onto the porch that once surrounded the house on three sides. There was no air conditioning in Rice’s day, Saage reminded the group. “You’d follow the shade around the house and live outside,” he said.

As the students moved from room to room, the home’s history began to take shape. The kitchen was a separate structure that would have been built away from the house, Saage said, because of the risk of fire. Mosquito bars would have covered the upstairs windows in the summer. The couple would have spent leisure time relaxing on the second-floor landing. And the vast porch with its broad columns, Manca said, “provides the grandeur of ancient Greece right here in Houston, Texas.”

The Heritage Society has restored and maintains several historic buildings in Sam Houston Park. The Rice class also toured the nearby Kellum-Noble House, an 1847 plantation-style brick home in its original location.

In August, the Heritage Society will spotlight the home’s connection to Rice with a Rice University Centennial exhibit. The group is developing the exhibit with Lee Pecht, head of special collections at the university’s Fondren Library. The exhibit will explore even more of William March Rice’s life, from his business success to his vision for the Rice Institute – and it will feature the house he once called home.

Leave a Reply