Through most of the 20th century, Houston thrived. It was a one-horse industrial town, riding its location near the East Texas oil fields to continued prosperity. The city was also world-famous for having imposed the least possible controls on development of any city in the Western world. Houstonians proclaimed themselves to be the epitome of what Americans can achieve when left unfettered by zoning codes, government regulations or excessive taxation.

More than 80% of the city’s primary-sector jobs in 1980 were associated directly or indirectly with the value of oil, and the price of a barrel increased tenfold between 1970 and 1982, with no lessening of world demand.

About this time, a Rice professor had an idea that would shape the trajectory of his professional life and his adopted city for the next half-century.

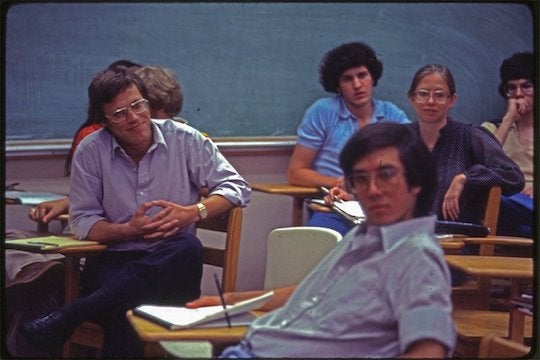

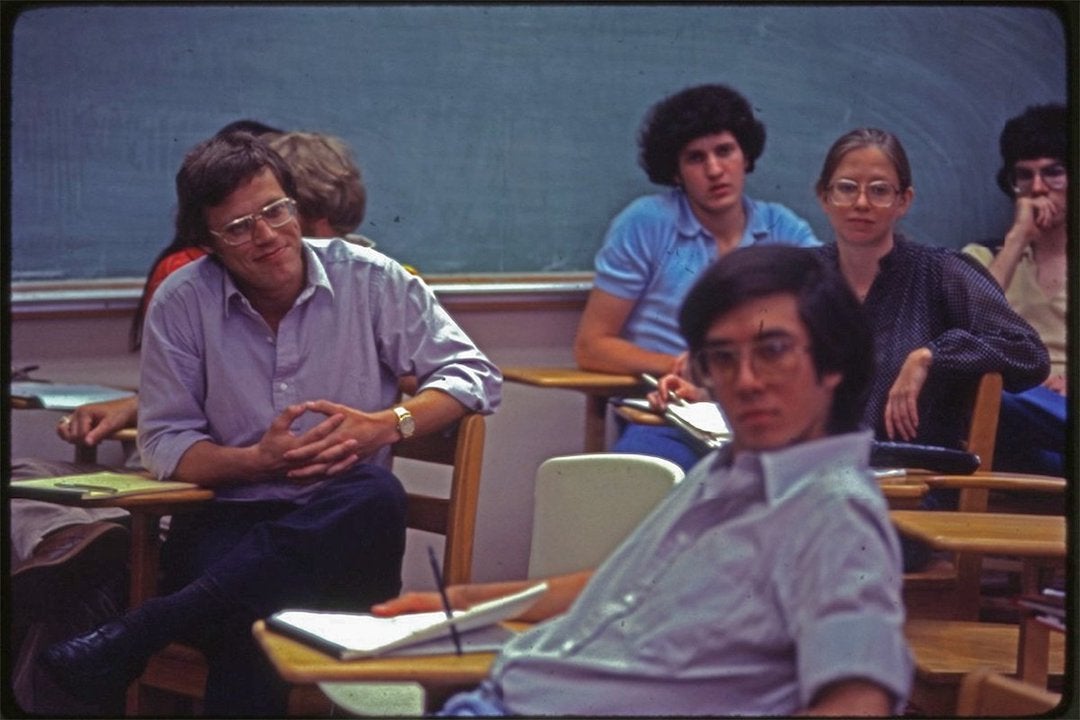

In the fall of 1981, Stephen Klineberg, an associate professor of sociology, was preparing to teach a research methods course the following spring. He originally thought of getting the class involved in developing a survey that would compare Rice freshmen and seniors in their assessments of the university and their perspectives on their personal futures.

Then, quite unexpectedly, a more intriguing possibility arose. Two friends of his had just launched a new professional research firm in Houston called “Telesurveys of Texas” and were looking for new projects to increase its visibility in the community. With the help of the firm, Klineberg and his students would have an opportunity to study Houston itself, to conduct a systematic survey to measure how residents were assessing life in the area and to get a sense, through objective sociological research, of the kind of city its inhabitants were hoping to build with all that oil-based affluence. The research on student attitudes at Rice would have to wait.

The 1982 survey included a variety of questions designed to measure the ways area residents were balancing the exhilaration of the city’s spectacular expansion with rising concerns about the social costs of its unfettered growth, such as the mounting challenges of traffic congestion, the spread of toxic pollution and soaring crime rates.

Then, suddenly, just two months after that first survey was completed, the boom collapsed. A global recession suppressed the demand for petroleum products just as new supplies were coming onto world markets. The price of a barrel of oil fell from $35 to $28 almost overnight, but Houston’s business community had been building and borrowing in the confident expectation of $50 barrels. By the end of 1983, this once-booming region recorded a net loss of more than 100,000 jobs.

It was clear that it would be good to conduct the survey again with a new class the following spring to measure residents’ reactions to the sudden turn of events. And as the city emerged from the deep recession in the late 1980s into a rapidly changing America, Klineberg continued to offer the class and conduct the survey — and has every year since.

Funding the surveys

In the early years of the surveys, Klineberg would crisscross the Houston region sharing the findings, delivering about 100 talks a year because, as he puts it, the surveys are a resource that “belong to the people.” In response, a growing consortium of local foundations, corporations and individuals stepped forward to provide the funds that would ensure the continuation and expansion of the annual surveys.

In 2010, Klineberg and his sociology colleague Michael Emerson founded the new Institute for Urban Research at Rice. The primary goal of the institute, Klineberg said, was to continue and expand research on urban societies and to ensure that the data collected would be used to inform and inspire the broader community on which the research is based.

Soon after the launch of the institute, a Houston Chronicle editorial celebrated the promise of the newly inaugurated think tank, calling the three decades of survey findings “an unparalleled achievement … the longest-running close examination of any city’s economy, beliefs and population in the United States. … It’s no exaggeration to say that the Rice institute could one day shape decision-making for other cities as well.”

Later that year, the institute received what Klineberg described as “the gift of a lifetime” — a transformative donation from Houston philanthropists Nancy and Rich Kinder. The couple endowed the institute with a $15 million gift, and in their honor it was renamed the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, with the annual survey becoming the Kinder Houston Area Survey.

The Kinder Houston Area Survey became the basis for Klineberg’s 2020 book “Prophetic City: Houston on the Cusp of a Changing America.” Klineberg describes the book as “the story of Houston as told by the people of Houston,” combining quantitative findings from the first 38 years of systematic surveys with intensive interviews from more than 60 area residents from the city’s varied communities.

Student voices

The recipient of 12 major teaching awards at Rice, including the prestigious George R. Brown Lifetime Award for Excellence in Teaching and the Piper Professor Award, Klineberg retired from instruction in 2018 into the status of professor emeritus of sociology.

Throughout his teaching career, he touched the lives of countless students. His class, recalled Albert Wei, was the “birthplace of deep conversations around how we want to live, what we imagined for the future of whatever city we lived in and what values were rooted in how a city serves its people.” Wei, who graduated in 2012, now serves as the chief innovation officer at ProUnitas, a Houston nonprofit dedicated to connecting students with the support services they need.

Wei said Klineberg’s positive energy was infectious. “I even started to roll up my button-up shirt sleeves to three-fourths of their length, like he always did in lectures, when I started working in the classroom as a teacher,” he said.

“I am lucky that, years after our first meeting, I still get to sit down with Dr. Klineberg and talk about how Houston is changing and why it matters,” said Alec Tobin, a student in Klineberg’s final class who is now a research fellow at the Kinder Institute and assisted with this year’s 41 st Kinder Houston Area Survey.

Transformations and challenges

Looking back over the 41 years of surveys, Klineberg said three big themes have emerged as the most compelling long-term challenges facing the city, state and country today:

· The knowledge economy. To prosper in today’s high-tech, global economy, Houston will need to drastically improve its public schools and nurture a far more educated workforce. The surveys have shown that area residents are much more prepared today than in past years to support government initiatives to reduce disparities in opportunity and to significantly increase investment in public schools — from birth to college to career.

· The demographic transformation. If the region is to flourish, it will need to evolve into a much more united, equitable and inclusive multiethnic society, one with real equality of opportunity for all residents. Here, too, the surveys have shown that area residents, increasingly over the years, are embracing Houston’s diversity and feeling more at home in a world of thriving friendships across ethnic populations, religious groups and sexual orientations.

· Quality-of-place attributes. To attract the talent that will grow its economy, the city will need to continue making major improvements in its parks and bayous, its mobility and transit systems, its air and water quality, its venues for sports and the arts, and its resilience to severe storms and rising sea levels. The surveys have shown how much area residents value these quality-of-life amenities and recognize the critical need to mitigate future storms.

Klineberg said it remains to be seen whether Houston’s business and civic leaders can build on the attitude changes the surveys reveal and can summon the political will to impact change.

Into the next 40 years

As he nears retirement from Rice, Klineberg says he’s tremendously grateful for the support of so many over so many years, and he remains optimistic if still concerned about the long-term future of his adopted city. A new fund to provide financial support for the Houston surveys in perpetuity, the Stephen L. Klineberg Legacy Fund, is being established.

“I commend Dr. Klineberg for his exemplary leadership and immeasurable contributions to improving our city,” Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner said. “His vision will live on through the important work of the Kinder Institute and will continue to be an instrumental resource for generations to come.”

Klineberg is even more grateful for the support of his beloved family. In June, he and his wife Peggy will celebrate 60 years of marriage. And in what he thinks of as “truly magical,” four of his five grandchildren are Rice alums.

In a letter celebrating Klineberg’s legacy, Emerson wrote: “Without Steve Klineberg, there would be no Kinder Institute.”

Rose Rougeau is the senior director of external affairs at Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research. Her original post in the Urban Edge blog is available here.