McDaniel’s newest book shows historic connections between slavery and convict labor

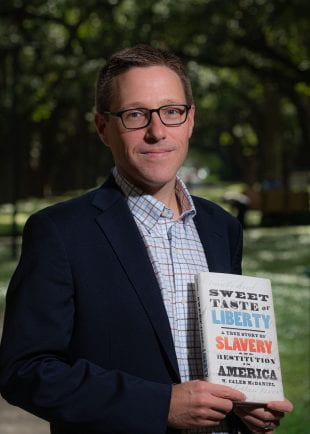

A new book from Rice history professor Caleb McDaniel presents the previously little-known story of Henrietta Wood, who survived enslavement twice and, 30 years after she was first freed, won the largest known financial settlement awarded by a U.S. court in restitution for slavery.

A new book from Rice history professor Caleb McDaniel presents the previously little-known story of Henrietta Wood. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow)

But McDaniel doesn’t stop there. Employing recent scholarship and years of research, “Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America” (Oxford University Press, $27.95) proves the connections between slavery and the convict labor system that arose after the Civil War.

Prison leasing arrangements across the country, including those of the notorious Imperial State Prison Farm in Sugar Land, Texas, continued to impoverish and incarcerate black men and women until they were ended in the 1920s.

Yet Wood’s successful lawsuit — she won $2,500 from Zebulon Ward, one of the men who enslaved her — demonstrates that African Americans fought from the beginning for redress and reparations. Despite recent attention drawn to the topic by U.S. House Judiciary Committee hearings this year during Juneteenth and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ award-winning “Case for Reparations” that still resonates five years later, this is not a new conversation.

McDaniel expands that conversation with the first book about Wood and the impact of her lawsuit. The $2,500 helped Wood’s son, Arthur H. Simms, attend what would become Northwestern University’s law school.

“When it comes to questions surrounding reparations today, there’s a fair question to be asked whether any amount of money could matter or make a difference,” McDaniel said. “Here’s a story that shows the difference even a small amount of restitution can make in a particular person and family’s life.”

McDaniel detailed the meaningful impact the settlement would have on Wood’s descendants in a recent article for Smithsonian Magazine. “Sweet Taste of Liberty” is dedicated to one of them: Winona Adkins, Wood’s great-great-granddaughter, who died a few months before the book was finished — but not before McDaniel worked with her and another Wood descendant to gather the kind of information about her life that wasn’t available in any archives or newspaper clippings.

Wood was one of the estimated 150,000 enslaved people brought to Texas during the Civil War by planters seeking to avoid the Emancipation Proclamation. This followed a five-year period during which she had been given her freedom papers and lived as a free woman in Cincinnati — where, she later recalled, she’d had her first “sweet taste of liberty” — before being kidnapped and forcibly enslaved once again in 1853.

In 1876, Wood gave an interview about her experiences as a twice-enslaved, twice-freed woman to the Cincinnati Commercial. Three years later, she told her story again to a reporter from the Ripley Bee. This 1879 interview was the first McDaniel had heard of her tale, after a colleague, fellow historian Richard Blackett at Vanderbilt University, showed it to him in 2014, knowing McDaniel’s research into the experience of enslaved people in Texas during the Civil War.

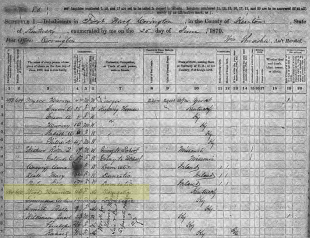

McDaniel has made much of his research openly accessible on a companion website, which includes records such as this 1870 Census document with Henrietta Wood’s information highlighted.

Ward, who had colluded in the kidnapping that eventually brought Wood to Texas, was the man Wood would eventually sue in 1870 for damages and lost wages. Ward could afford it: By that point, he had become one of the wealthiest men in the South thanks to his work overseeing prisons that employed convict labor.

“It’s a book about Wood, but it’s also about Ward, the man she sued, because he was an early architect of convict leasing systems in several Southern states,” McDaniel said. “Braiding those narratives together hopefully helps readers think about how those systems bled together as well.”

There were significant differences between convict leasing and slavery, McDaniel acknowledged.

“But often it was the same people engaged in both systems,” he said. “Both in terms of the victims of those systems and in terms of the perpetrators, it was the same cast of characters.”

As he dug into archives to confirm details in the interviews Wood gave, McDaniel was astounded by how much he was able to find out about her life and corroborate thanks to her detailed memories.

“It’s such an amazing story and I was amazed that I had not heard of it before,” he said. “There actually are a lot of stories of enslaved women from the 19th century that are yet to be told, if historians are willing to look for them.”

The personal narrative driving the story also makes “Sweet Taste of Liberty” eminently readable, an empathetic and touching account of one woman’s long fight for justice. That was critical to the National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar Program grant that funded McDaniel’s work: These annual grants help create books that are both intensely researched and intended to reach a general audience.

This was also important to McDaniel, who has made much of his research openly accessible on a companion website.

“One of the things history teaches you is empathy,” and along with it ways of viewing subjects such as slavery and reparations as more than just broad abstractions, he said. “Some of the books I’ve always enjoyed the most and learned the most from are the ones that can connect those big topics to a compelling individual story.”

Wood’s own words, woven throughout the book, bring these intertwining stories to life in a way that only personal narratives can. Historians of slavery, McDaniel said, are always looking for ways to overcome the neglectful or inhumane ways in which the lives of enslaved people were recorded by others — sometimes only as a number or a given name that wasn’t even their own.

“In this case we have a narrative that Henrietta Wood herself was able to share, so we have at least some sense of how she wanted her story to be told and which parts of her life were important for her to emphasize,” McDaniel said. Also critical is the immediacy with which Wood shared her story: telling it to lawyers, journalists, anyone who would listen, immediately after her first abduction and for as long as she had breath in her body.

“This book wouldn’t have happened without her determination to tell her story,” McDaniel said.

Caleb McDaniel will kick off a 13-city book tour with a reading Sept. 6 at 6:30 p.m. at Brazos Bookstore, 2421 Bissonnet St.