‘The Flip’ asks vital questions like ‘Are we just moist robots with computers on top?’

By his own admission, Rice University Professor of Religion Jeffrey Kripal writes — and lectures — “about very strange things.” He’s fascinated with near-death events, precognitive dreams, abduction narratives and other paranormal phenomena Kripal categorizes within the catch-all expression “extreme religious experiences” or, more simply, “the impossible.”

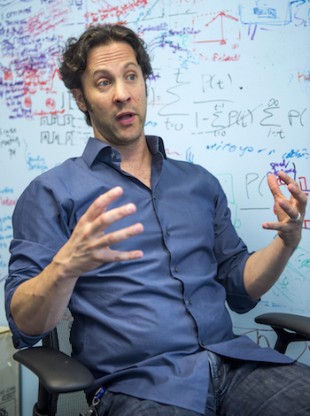

Rice Professor of Religion Jeffrey Kripal argues that humanity is swimming in a sea of shared stories of “the impossible.”

Try talking earnestly about these subjects at engineering conferences or neuroscience symposia and you might get laughed out of the room. Still, if you leave that room and have a beer with those same people, you may well hear very similar stories, and in a very different tone.

That’s Kripal’s point. He knows. He has listened to many such stories from many such scientists for almost two decades now.

The simple truth is that large numbers of people, including many scientists and medical professionals, report some very real dealings with such “impossible” things.

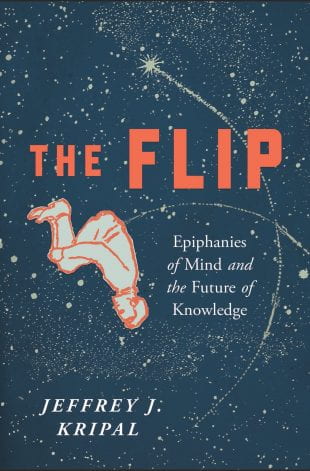

So perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that work like Kripal’s is once again gaining traction in academic circles. Enter Kripal’s latest book, “The Flip: Epiphanies of Mind and the Future of Knowledge,” which originated as a wildly popular article in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

In the 2014 article, Kripal argued that humanity is swimming in a sea of shared stories — strange tales of encounters with dead loved ones, of knowing things we couldn’t or shouldn’t know, of dreaming the future before it happens — which conventional or public science is quick to dismiss as “anecdotal” or “hallucination.”

This body of “rejected knowledge,” as Kripal calls it in “The Super Natural: Why the Unexplained Is Real,” could be a valuable source of answers to some fundamental philosophical and scientific puzzles — like the nature of consciousness or the “block” cosmological structure of space-time — yet conventional forms of science refuse to engage with it, missing some crucial potential clues, Kripal argues.

“We do not know how many such stories there might be, much less what they might mean,” Kripal wrote in the 2014 article. “We do not know because we have never really tried to find out.”

The article lit bonfires of discussion, and not just within the heady comments section. Within weeks, Kripal was approached by Bellevue Literary Press, a publisher that specializes in putting the humanities and the sciences in deep conversation, about turning his article into a book.

“The Flip” is the resulting manifesto, which also serves as a warning that our unwillingness to examine these persistent stories — and the reasons they occur across cultures and centuries — is not only a failure of our educational system and its often-siloed disciplines but also a betrayal of some of our deepest and most profound human qualities: curiosity, imagination, empathy, hope and the search for transcendence.

“The Flip” has drawn praise far and wide since its publication in March. “How to Change Your Mind” author Michael Pollan, whose own newest work explores what psychedelics can teach us about consciousness and death, called it “one of the most provocative new books of the year, and, for me, mind-blowing.” And just last month, Kripal’s talk at the Chicago Humanities Festival — which followed Melinda Gates — sold out within days.

What Kripal provides with “The Flip” is more than just a collection of peoples’ stories. He also provides a structural framework for discussing these experiences in a way that preserves intellectual integrity and moral power, a shared language that academics and laymen alike can access and use.

Writing counter to the Whorfian and postmodern conceit of language as a prison, Kripal instead argues that language, used with nuance in the forge of the intellectual’s imagination, can also free us. Talking and thinking publicly about these things allows us not only to share the stories of our experiences in an honest and transparent way, but also to plot new paths for exploring their scientific and humanistic implications — which Kripal suggests could be literally beyond measure.

Much of Kripal’s fluid prose calls to mind the best stand-up routines of philosopher-comedian Bill Hicks, who compared life to an amusement park attraction that’s “just a ride, and we can change it anytime we want.”

Although Hicks died in 1994, the comic’s work has only become more influential over time, perhaps as these shared schools of philosophy merge across fields. Comedians and religion professors aren’t, after all, the only people in the world interested in answers to the big questions.

We asked Kripal about Bill Hicks, “moist robots,” Rice alum David Eagleman, the oft-cited crisis of the humanities, the origins of consciousness and other pressing questions. An edited transcript of the conversation follows:

Kripal’s latest book, “The Flip: Epiphanies of Mind and the Future of Knowledge,” originated as a wildly popular article in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Rice News: Did you follow Bill Hicks’ stand-up? One of his most famous lines is, “We are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively. There is no such thing as death. Life is only a dream and we are the imagination of ourselves.”

Jeffrey Kripal: Forgive me, but I have never heard of him. Do you think he believed that, or do you think that’s just a line to get a laugh? Did he have some kind of experience? Do you know where he got that?

That was inspired by an acid trip, I believe.

OK, that’s where he got it from, then: a classical psychedelic opening. And that, of course, is also how such convictions are immediately dismissed by those who have not been so opened: it was “just the drug.” Except it probably wasn’t. It is just as likely that such powerful molecules shut down brain function to let real things in, after all. The history of religion is filled with similar openings, from the ancient world to today. One could write a whole history of psychoactive plants and the sacred. People, moreover, have these sorts of experience in all kinds of other situations and contexts, from car accidents and illness to aesthetic experiences of natural beauty and musical genius.

One of the scientists I write about in the book, Bernardo Kastrup, thinks the same, actually almost to the letter. He writes that we are all “alters” of a single mind or consciousness — like in a personality disorder with multiple alters or separate personalities. For Kastrup, we are all personalities in a single cosmic mind or consciousness, and he means it. It’s a very, very old conviction, actually. It is everywhere in comparative mystical literature, for example.

Kastrup is not being simply poetic or metaphorical. He knows that. And we’re talking about a professional scientist who worked at CERN and had a very serious set of experiences or openings that he is thinking out of. But how do you convince someone who hasn’t had such an experience, opening or uncovering?

OK, so how do you approach discussions of these supernormal experiences with someone who hasn’t really had one?

Well, I’m going on nearly 40 years now studying these things, tracing them in the history of religions, and working very closely with contemporary experiencers. So, I have read and heard similar things so many times, from so many angles and within so many cultures, that the fundamental claims just ring true to me now. For me, then, the truth emerges gradually from a lifelong process of lining such “impossible” events up, looking at them very closely with a critical but sympathetic eye, putting them all on a shared comparative table, and finally seeing them all together as a single whole. So you don’t technically need to have such an experience to appreciate the power and possible implications of such openings: robust comparison or a sufficiently rich natural history of the impossible can get you to a similar place. But I recognize others do not have the time or training to do all of that. That’s why I write.

So, it’s about a wealth of data for you?

Yes! But historical and autobiographical data that historians and humanists work with, data that you cannot control. No, you can’t replicate these experiences in the laboratory; no, you can’t measure them; no, they will not behave according to any scientific method we have. So? They are still real. They are still a part of our world and the historical record. Indeed, for the people who know them, they are often the most real and important events in their entire lives. And they have certainly driven much of the history of religions. No doubt about that.

And yet there are other things that behave unexpectedly but which we accept as real, like at the quantum level.

Quantum physics makes a major appearance in “The Flip,” not as the physics but as the physicists, as the human beings who think about the philosophical implications of the quantum realm, which appear to be as revolutionary as they are strange. I have spent weeks, then months, with such physicists. They have taught me what the physics can tell us, and what it cannot. What it can tell us about is the structure and behavior of matter. What it cannot tell us about is what matter is. So not only do we not really know what “mind” is; we do not really know what “matter” is either. And many of these physics colleagues think these two big questions are somehow connected, that the “is” questions with regard to mind and matter might well be two sides of the same flipping coin. That’s the wager of the book as well.

In any case, I doubt if people really understood the quantum level, they would accept it as real. I don’t honestly think human beings are very good at accepting reality, actually, much less understanding it.

I’m not the least bit interested in uncritically accepting any particular belief system around such ultimate matters, then. I mean, there are all kinds of beliefs that get wrapped around these experiences, but I don’t think they’re necessary to the experiences. Consider again your comedian, Bill Hicks. Was he a Christian? Was he a Buddhist? I don’t know. But he could have went in any number of directions with that kind of cosmic experience, from “God” to “nirvana.” Others certainly have, like the neuroanatomist Jill Bolte Taylor, whom I discuss in the book. She described her own “flip” — catalyzed by a massive stroke on the left side of her brain, that is, an overwhelming compromise of brain function — as an entrance into an oceanic bliss-filled “nirvana.” But Hicks didn’t adopt any religious register, not at least in the pieces you shared with me.

Yeah, he was your average Houstonian growing up in the suburbs in the 1980s. So, you’re saying it’s not necessary to have the experience of “the flip” yourself in order to be empathetic or understanding of others’ experiences.

It helps. But I don’t think it’s absolutely necessary. I certainly hope it’s not absolutely necessary. That is what I think a good education is about: giving us the ability to imagine and understand things we have not experienced.

There’s the whole Whorfian argument of language as a prison, but you also need language to discuss these experiences, right?

Yes. And not just to discuss. To conjure. You need poets. There’s a Tristan Harris piece that is essentially about him locking himself in a room and trying to figure out a language to capture what’s happening to us because of the digital world. He’s completely convinced that it’ll only be addressed if we can get the right language. And I think that’s basically the same argument that I’m trying to make — that we need a radically new language here before we can understand ourselves and create a new sustainable and truly cosmic culture. We need a new intellectual poetry.

I travel and lecture a lot at many universities about very strange things. And one of the things that I find very often is that the academics from the humanities, the social sciences, and the sciences who come to the lectures are almost always deeply sympathetic. They ask me again and again, “What do you do with all the pushback?” And I answer, “What pushback?”

I don’t get much pushback — at least in person. I get some online, yes. But the response I most commonly get goes something like this: “Wow, I’m so happy you’re doing this. You can make the most unbelievable things sound Ivy League.” I think what they are trying to say is that, when someone comes in and starts talking about these things in their own academic language, using anthropology, history, and neuroscience, they realize: “Oh, we can actually do this — we can actually talk about this and not sound like fools.” That’s what they most fear: they fear sounding like the tabloids.

Some of the falsehoods that float around hardly help. One of the pieces of nonsense that’s out there is that these kinds of extraordinary or “impossible” experiences only happen to people who don’t know their science or aren’t smart enough. That’s just false, but people believe it because no one stands up and tells them it’s wrong. I’m standing up. Trust me: it’s factually, historically, and absolutely wrong. “The Flip” is filled with stories from the lives of serious scientists, including Nobel prize winners, that demonstrate this definitively. Let it go.

Yes, the stories that you collected in here refute that idea.

They’re mostly stories from scientists, engineers and doctors. I did that intentionally. The first chapter has a few non-science types, but the whole point of the book was to say, “No, actually, this happens to scientists all the time.”

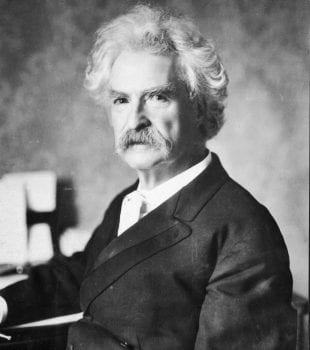

A portrait of American writer Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens, 1835 – 1910), circa 1900. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

I thought it was interesting that you specifically opened with Mark Twain, who I think is revered for his intellectual honesty and for, well, making fun of everything.

Well, he didn’t make fun of his own precognitive dreams and clairvoyant experiences, of which he had all too many and called “mental telegraphy.” (Twain’s dream of his brother’s death and funeral, which occurred as in his dream a few weeks later, opens both “The Flip” and Kripal’s original article for the Chronicle.)

He was one of those people who was afraid that he wouldn’t be taken seriously, that something so sincere to him might be mocked by other people.

He wrote two pieces for Harper’s Weekly, which was one of the big magazines of the time. It is significant that Twain wanted them to publish both pieces anonymously — that’s how worried he was. And that’s why we don’t understand these things. We keep self-censoring. We keep suppressing the real data through what amounts to a kind of public shaming.

Something that struck me early on was that you kind of seemed to hint that the way forward is neither religious nor scientific but maybe something more holistic — maybe something different?

We don’t have that language, again. We think things are either subjective and in our heads and so fluffy and unreal, or that they are physical and hard. But the truth is that most all of our human experience — really, all of it — is somewhere in between those two stark choices.

Our departments and our disciplines in the universities split that one world up in ways that I think are useful, and I understand why we do that, but in the end these artificial divisions are becoming less and less helpful, if not actually dangerous and destructive — witness our ecological crisis, generated largely because we believe that “nature” is “out there” and “not us.” So, no, I don’t think we know our true cosmic condition, but I think it lies somewhere in a fusion or transcendence of the subjective/objective split. This is what I call the future of knowledge. It’s where I believe we need to go next together.

One of the things you wrote that stuck out to me was this: “The great crisis of the humanities is that they study nothing.” Can you go into that a bit more?

It’s a provocation, not a literal statement. The argument there is that, if we truly believe what we might call the materialist consensus, namely, that there is only matter, that matter is fundamentally mindless and dead, and that consciousness is basically an illusion created by purely material brain processes, then the humanities, which study the productions and expressions of human consciousness, are literally studying nothing. We’re just studying an illusion, a nothing. And, in this same consensus, the scientists are studying what’s really real, which is the material world. All of this just follows logically from the first premise that mindless matter is all there is. I don’t see a way around that, as long as we accept that premise. I don’t. Nor do a lot of intellectuals these days. They’re flipping.

What “the flip” is, in sum, is a little language, a two-word poem for all of those life-changing experiences in which a person realizes that consciousness or mind is not just the “fluff” or illusion of matter, that mind or consciousness is as fundamental to the physical universe as matter is. Mind is mattered, yes, but matter is also minded.

When you make such a “flip,” or such a flip makes you, suddenly the humanities become something entirely different. They become the study of everything. They become literally cosmic. That is what I am trying to say.

I love the radio wave analogy that you have in here. It’s like, if we have a radio and we turn the radio off and the voices inside of it go away, that doesn’t mean that the radio signal is just gone from the world, or that the voices are “in” the radio. But this is exactly how we think of consciousness: that it is “in” the brain” and “goes out” when the brain goes out.

Yep, that’s an old metaphor in the philosophy of mind recently reworked by the neuroscientist David Eagleman. David is a Rice alum.

How does science reconcile itself to some notions but not others?

It is all a function of their models and what those models include and exclude. The scientific method works beautifully by manipulating material processes in very controlled and rigorous ways and then seeing what happens. It is fundamentally about observation, control, measurement and replication. The problem is that such a method can explain almost anything, except us — which includes, of course, the scientists doing the science. Little of this works, after all, when we are trying to understand something that cannot be observed, controlled, measured or replicated. I think the mistake that some scientists make is that they assume on some level that anything that can’t be established with such a scientific method isn’t real. That does not follow, of course, but that is the underlying assumption.

This kind of materialism is an interpretation of science, of course. It’s not science. But, unfortunately, a lot of very prominent or at least very public scientists conflate the two and so do endless damage to the larger conversation. That conflation is one of the things the book is trying to question.

We must also honor the power of materialism. To speak more emotionally, when you see someone die, the person does seem to go out like a lightbulb. You can understand why people would think there’s nothing there after the brain goes dead. But, on the other hand, people also appear to loved ones after their brain goes out. So, there’s real data, real experience, on both sides, even if the data on the one side will not play by the rules of the scientific method. There are good and understandable reasons to accept either one.

At the end of the day, the new book is about what you think a human being is, what you think you are. Are you an organic biological robot? An illusion that will blip out when the body-brain stops functioning? Or are you an expression of something fundamentally beyond your little person and body, something literally and truly cosmic?

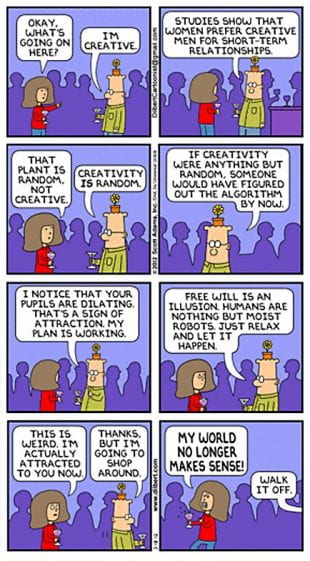

What did you call it in here? A “moist robot,” I think?

I believe that is from the comic strip “Dilbert,” by Scott Adams. But that’s precisely the question: Are we just moist robots with computers on top, as one of my Ph.D. students once sarcastically put it? Or are we a biological expression of a conscious cosmos temporarily experiencing itself in and as a human body and person? Really, the latter framing is a kind of nonreligious way of saying something fundamentally religious, something profoundly spiritual.

And such questions, I assure you, will not go away, however uncomfortable they make some of us feel and however far science advances. They will not go away because the science is just getting weirder and weirder, and — my own wager now — this is who and what we really are. Everything spins on that human dime, which is also, I dare add, constantly “flipping.”